‘They are killing us’: Murders of women in Cuba are growing at an alarming rate

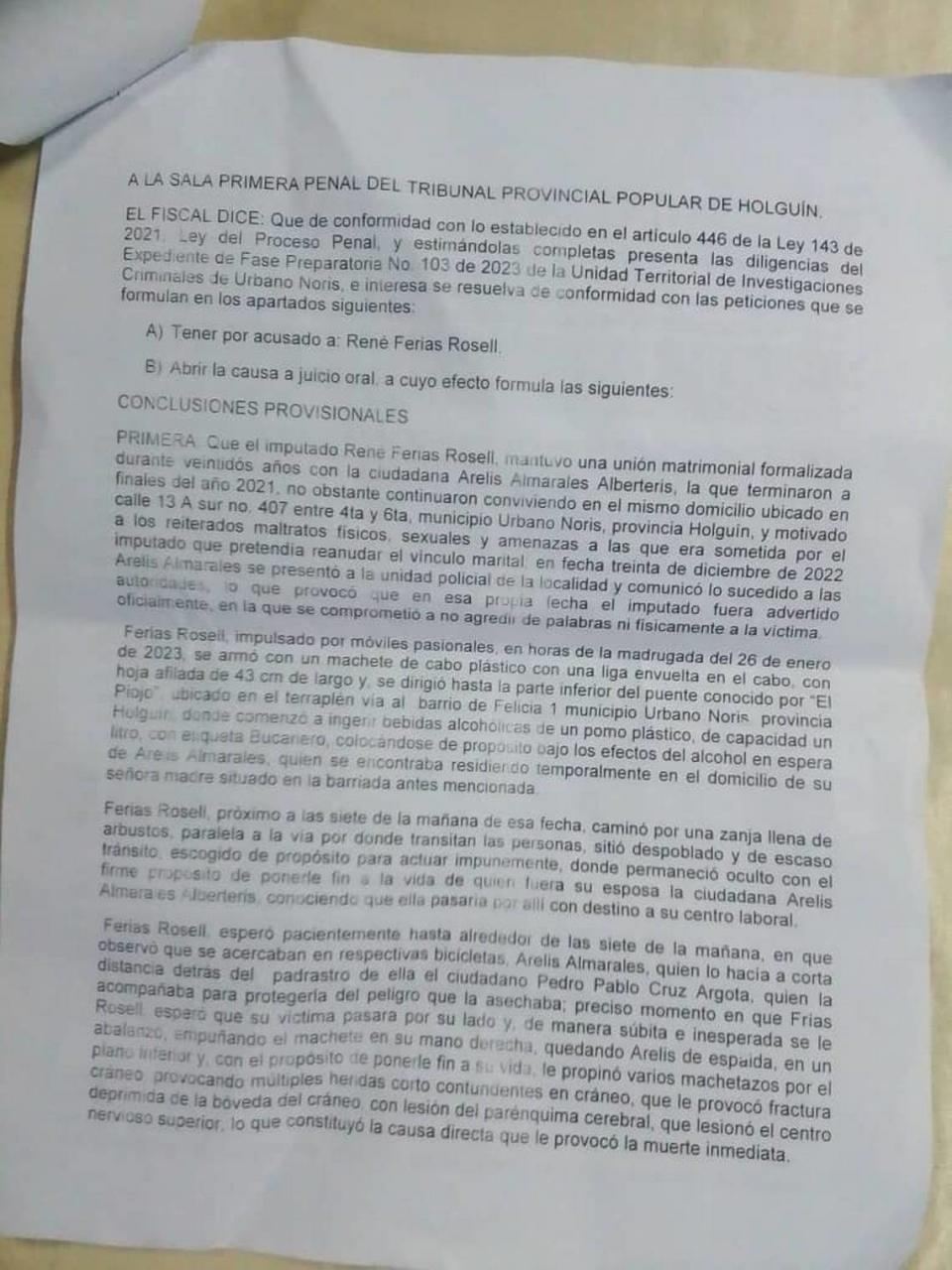

In the first days of this year, Arelis Almarales Alberteris told her mother she was happy. She had gotten divorced the year before and left the house in a small town in Holguín, in eastern Cuba, where she had lived with René Ferias, her husband of 22 years.

A few days later, at dawn on Jan. 26, Ferias attacked her with a machete and killed her.

“Imagine seeing your daughter hacked to pieces by a nasty man, who had not even been her husband for over a year, because he found out that she had another relationship,” said her mother, Nancy Alberteris.

On Dec. 30, 2022, Almarales, 40, had gone to the local police station to complain that Ferias, 50, had threatened her and raped her. Questioned by police, Ferias “promised not to verbally or physically attack” his ex-wife, according to the prosecutor’s indictment.

“He cried and swore before the police that he was never going to mess with her again,” Alberteris recalls of the day she accompanied her daughter to make the complaint.

A month later, around 7 a.m., Ferias hid under a bridge, armed with a sharp long-bladed machete, according to official documents. There, he remained hiding and drinking, until Almarales, who left her mother’s house for the nursing home where she worked as a physical therapist, passed by on a bicycle.

“I passed by ahead of her, and I didn’t see him,” said her stepfather, Pedro Pablo Cruz Argota, who accompanied Almarales to work on another bicycle. The next thing he heard was the gasp of his stepdaughter.

“I threw the bike, looked back and saw him hitting her head with a machete. I picked up two stones, and he told me that if I hit him with the stones, he would cut me with the machete just the same”, Cruz Argota said.

Then Ferias, described in the prosecution documents as “violent” even though he had no criminal record, turned himself into the police.

Almarales is one of the 59 known victims of feminicides in Cuba in 2023, according to records kept by Cuban independent groups since 2019 in the absence of public government statistics. A feminicide is the killing of a woman specifically because she’s a woman, in contrast to a homicide that happens, for example, during the commission of a robbery.

These groups believe that the actual numbers may be higher, but even so, what they have compiled indicates that these crimes — like violence in general — are on the rise on the island, especially in the capital, Havana. In recent years, the country has grappled with increased poverty after the COVID-19 pandemic, a sharp drop in tourism and economic restrictions imposed by the Donald Trump administration which remain in place.

So far this year, the independent groups have documented 23 more deaths of women victims of gender-based violence than in 2022, when at least 36 women died.

In comparison, Spain, with a population four times that of Cuba, reported 49 such killings in all of 2022, according to official figures from the Spanish Ministry of Equality.

In Cuba, most such homicides are committed by partners or ex-partners, according to Alas Tensas Gender Observatory, an independent group that reported cases for the first six months of 2023. Most happened in the victims’ homes, “confirming that the most dangerous place for women is their own home,” the report said.

However, some of the killings also happened at state institutions.

A neighbor from the city of Nuevitas, in the central province of Camagüey, told the Miami Herald that in February, 17-year-old Leidy Bacallao went to a local police station asking for help after several threats from her ex-partner, 50-year-old Elesván Hidalgo. In front of the police officer, while she was making the complaint, Hidalgo hacked her to death with a machete.

Also in February, Arianny Chávez Puche, 35, was killed by her ex-partner while working as a telephone operator at the Provincial Pediatric Hospital in Las Tunas, in eastern Cuba, according to several independent media sites.

Keeping silent

For many years, Cuban authorities have kept silent about the rising numbers of murdered women. Until now, the official position has been that Cuba is free of such crimes. In 2015, the sexologist Mariela Castro Espín, daughter of leader Raúl Castro, told Tiempo Argentino newspaper.

“We do not have, for example, feminicides. Because Cuba is not a violent country,” said Castro Espín, the director of the National Center for Sexual Education.

Although men have been in charge of the government since 1959, Fidel Castro emphasized including Cuban women in all aspects of life. Some policies to broaden access to employment and expand the right to abortion in the early days of the Revolution had placed Cuba at the forefront of debates on women’s rights, and incidents of gender-based violence contradicted this image.

For the first time in 2019, Cuban authorities shared some data with the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, a regional United Nations agency, from a survey conducted by the government in 2016. That year, the feminicide rate on the island was 1 per 100,000 females aged 15 or over, a total of about 50 deaths. That is low compared to countries such as El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico or Brazil, but higher than rates in Peru, Chile or Panama.

The survey also revealed that 27% of the women interviewed had suffered some type of violence at the hands of their partners, and only 4% sought help from state institutions to deal with the situation.

According to the statistical yearbooks published by the Cuban Ministry of Public Health, women’s deaths due to violent assaults grew from 96 in 2020 to 130 in 2021. However, the ministry does not clarify how many of these involved women specifically targeted because of their gender.

Amid reports about the increase in the killings of women by their partners or ex-partners, Castro Espín reversed her public position in 2022 and proposed including feminicide as a punishable crime in the new Cuban penal code.

Many countries have laws against feminicide as a specific crime to draw attention to killings targeting women and facilitate their proper investigation, prosecution and record-keeping.

Many Cuban activists had been advocating for such a proposal, which the Federation of Cuban Women, the only legal women’s organization in the country, did not support.

The Cuban National Assembly eventually rejected the amendment proposed by Castro Espín that same year. But for the first time, Cuban law explicitly considers gender-based violence as an aggravating circumstance when determining prison sentences for homicides.

The Herald could not contact Teresa Amarelle Boué, the general secretary of the Federation of Cuban Women. The organization, under government control, does not have a website or public press contacts. A comment request sent to her Facebook account was not answered. Neither was a request sent to an email linked to the organization’s international relations department.

For Marta María Ramírez, a Cuban journalist and feminist activist, including feminicide as a crime in the penal code “would make it possible to prevent them and establish protocols. It would make it possible to count them, to name and provide reparations so that the families know that their mothers, their daughters, their friends, did not die because they asked for it, but because they were women, trans women, non-binary, in a system that doesn’t protect them.”

Punishing gender-based violence

Many Cuban families demand more severe sanctions in such murders. Alberteris, the mother of Arelis Almarales, disagrees with the sentence imposed on the murderer of her daughter — 30 years in prison.

“He deserves more than that,” Alberteris said.

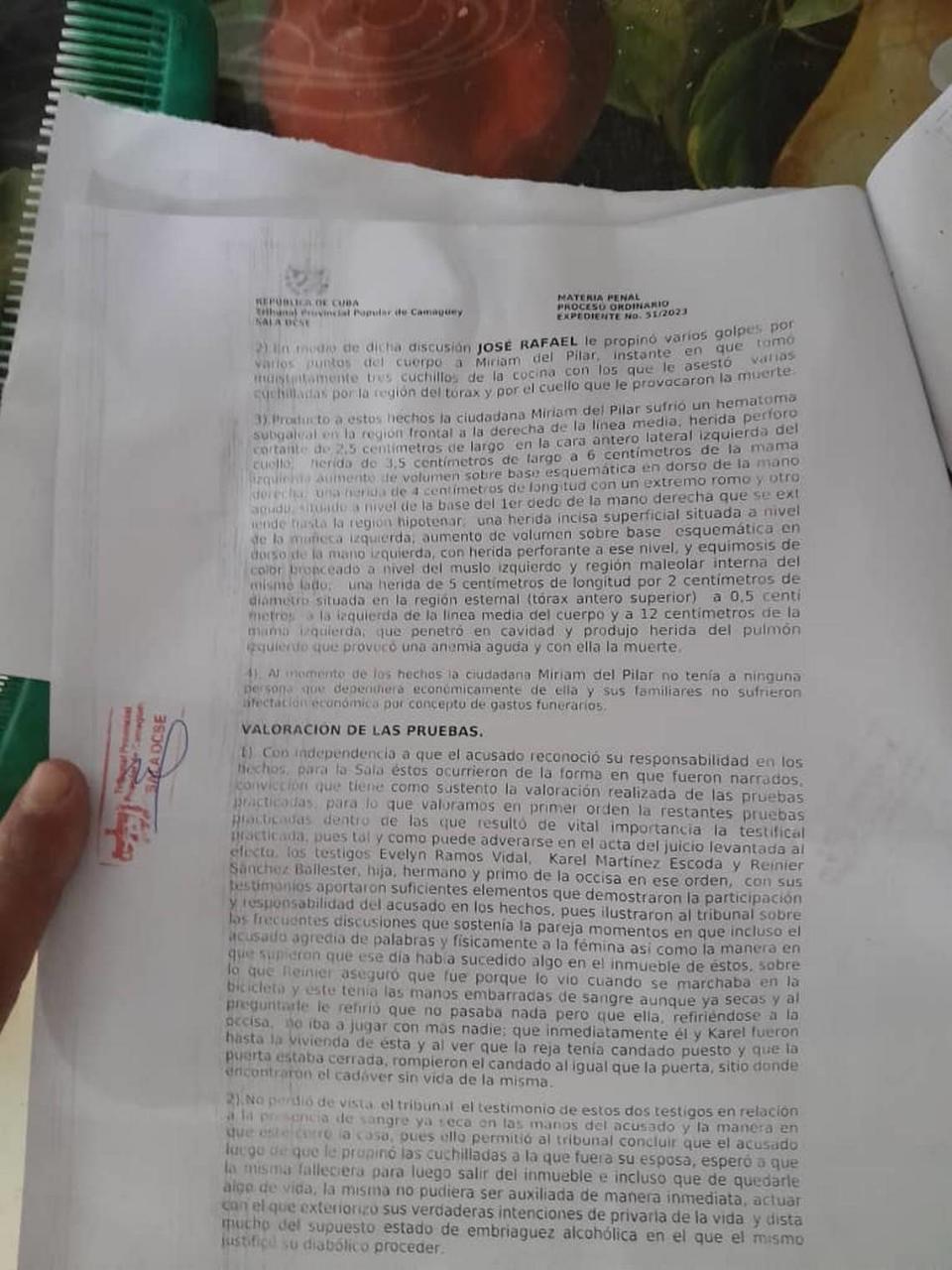

Karel Martinez Escoda, a Cuban doctor, was also disappointed when his lawyer told him prosecutors had asked for a 25-year sentence for José Alonso, who killed Martinez’s sister, Miriam Vilar Escoda. Alonso had been Vilar’s partner for two years. Martinez immediately sent a letter to the Cuban Supreme Court showing his disagreement with the sentence. He has yet to get a response.

On Dec. 7, 2022, he had to break down the door of the house where his sister lived in Camagüey and where he found her lifeless on the kitchen floor. The sentencing document from the People’s Provincial Court of Camagüey reviewed by the Herald said that Alonso “inflicted several blows on various points” of her body and, using three different knives, “dealt several stab wounds” to her chest and neck, causing her death.

“He killed her, bathed her, cleaned the blood and rode his bicycle to the bakery where he worked,” says Mireilys Rollán Pino, 54, a friend of the victim, who was present when the police removed the body of Vilar from the scene.

Alonso was charged with murder. According to the new penal code, whoever “deprives a woman of life as a consequence of gender violence” can be sentenced to life in prison or death. So far, only two men are known to have received a life sentence after having killed women in 2022.

Because Alonso “had no criminal record” and “maintained a normal social conduct,” the judges decided to “adjust the sentence to the middle” and condemn him to 25 years in prison, the court document said.

Despite the families’ complaints about the prison terms, Cuban defense attorney Nelson González said that in recent years, prosecutors’ policy has been to seek harsher sentences for crimes related to gender-based violence.

“That’s something we are seeing. There is greater prosecution and care about this issue,” he says. “You realize that the courts are more demanding with the sentences.”

Feminist activism in Cuba

So far, feminist activists and non-government groups have been doing the heavy lifting to provide more visibility to gender-based crimes in Cuba, helping relatives to report the killings, tracking their numbers and putting pressure on Cuban authorities to speak publicly on the subject.

“A single violated woman is not only a blow to the feminist tradition of the Revolution, it is an unacceptable act in our socialist society,” President Miguel Díaz-Canel said in April. He assured Cubans that there would be “zero tolerance” for gender-related killings.

However, activists say that the Cuban government has not shown a willingness to work on proposals such as a comprehensive law against gender-based violence — Cuba is the only country in the Western Hemisphere that does not have one. Such a law would provide a “comprehensive” response to gender-related violence, “from prevention to protection,” making it easier to coordinate issues like health care for the victims or the judicial response to the crimes, the independent Women’s Network of Cuba said in a statement earlier this year.

Nor has the government responded to a request from a dozen independent Cuban organizations to declare a state of emergency due to gender-based killings in the country.

“The Cuban state is a feminicidal state, a state that does not legislate, that does not have effective protocols, that turns a deaf ear to our demands, to people’s cries for help,” Ramirez said.

Activist Marthadela Tamayo, a member of the non-governmental group Cuban Alliance for Inclusion, the Cuban government “makes the real situation of violence and feminicide invisible.” Instead of focusing on eradicating gender-motivated violence, Tamayo said the government and its state security forces are more interested in trying “to silence, dismantle, make invisible and criminalize feminist activism in Cuba.”

After years of demands from activists, the Federation of Cuban Women created the Cuban Observatory on Gender Equality in June. But activist groups said it is inefficient in dealing with violence against Cuban women, among other things because it fails to report targeted homicides of women. While independent groups reported 36 victims in 2022, the federation disclosed only 18 because it only lists cases where attackers have already been tried and sentenced.

Likewise, the independent groups said that a telephone line established by the federation in 2020 that supposedly supports victims of gender-based violence handles several other social issues, and it is not really providing the services these women need.

The activists have also advocated for creating shelters to help women at risk and point out that the country lacks protocols to issue alerts when people go missing.

Independent groups reported an increase in the disappearances of women in 2022, which in some cases ended in their deaths. That was the case of Yeniset Rojas Pérez, from the central province of Villa Clara, whose mother even asked the Cuban leader Díaz-Canel to get involved in searching for her daughter but received no response. Her body was found almost a year later, this January, and a suspect was arrested, her family said, without providing further details.

Psychologist Lilian Rosa Burgos Martínez recommends that women in risky situations in Cuba find “some kind of support in someone trustworthy, and move away from the aggressor.”

“It may be that there is no safe institution in Cuba where the woman feels protected, but in that case, you have to look for safe and effective networks,” she said.

Given the lack of resources from the state, the feminist platform YoSíTeCreo — I Do Believe You — created a support line for people affected by gender-based violence, which provides counseling, legal advice and psychological help.

Other non-governmental groups such as Cubalex, Me Too Cuba, the Cuban Alliance for Inclusion, AfroAtenas, Cáritas Cuba and the Ministry of Women to Women in Cuba use social media, WhatsApp groups and dedicated phone lines to offer resources to women at risk.

Activist Yanelys Núñez, a member of the Alas Tensas Gender Observatory, said prevention work and public debate are also key in fighting gender-motivated violence.

“It is not only necessary to document the cases, but also to work on prevention in schools, in the public media, raising awareness among the population, speaking openly about the issues and not criminalizing independent activists,” she said.

But activists alone cannot deal with the situation, said Burgos, lamenting that an alliance between the government and independent advocate groups in Cuba today is unlikely.

In the meantime, Burgos added, women keep dying.

“Now we see in social media that they are killing us,” she said. “But they have been killing us for a long time.”