'King of the Underground Railroad' Jermaine Wesley Loguen born in Maury Co.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The history of Maury County, Tennessee amazes me, in that it often reaches far beyond the bounds of its 616 square miles.

Some of the people who called this place home and many of the events that took place here have national implications. One person who has achieved national fame probably didn’t have very many happy memories of this place because he was born enslaved. His name was Jarm Logue.

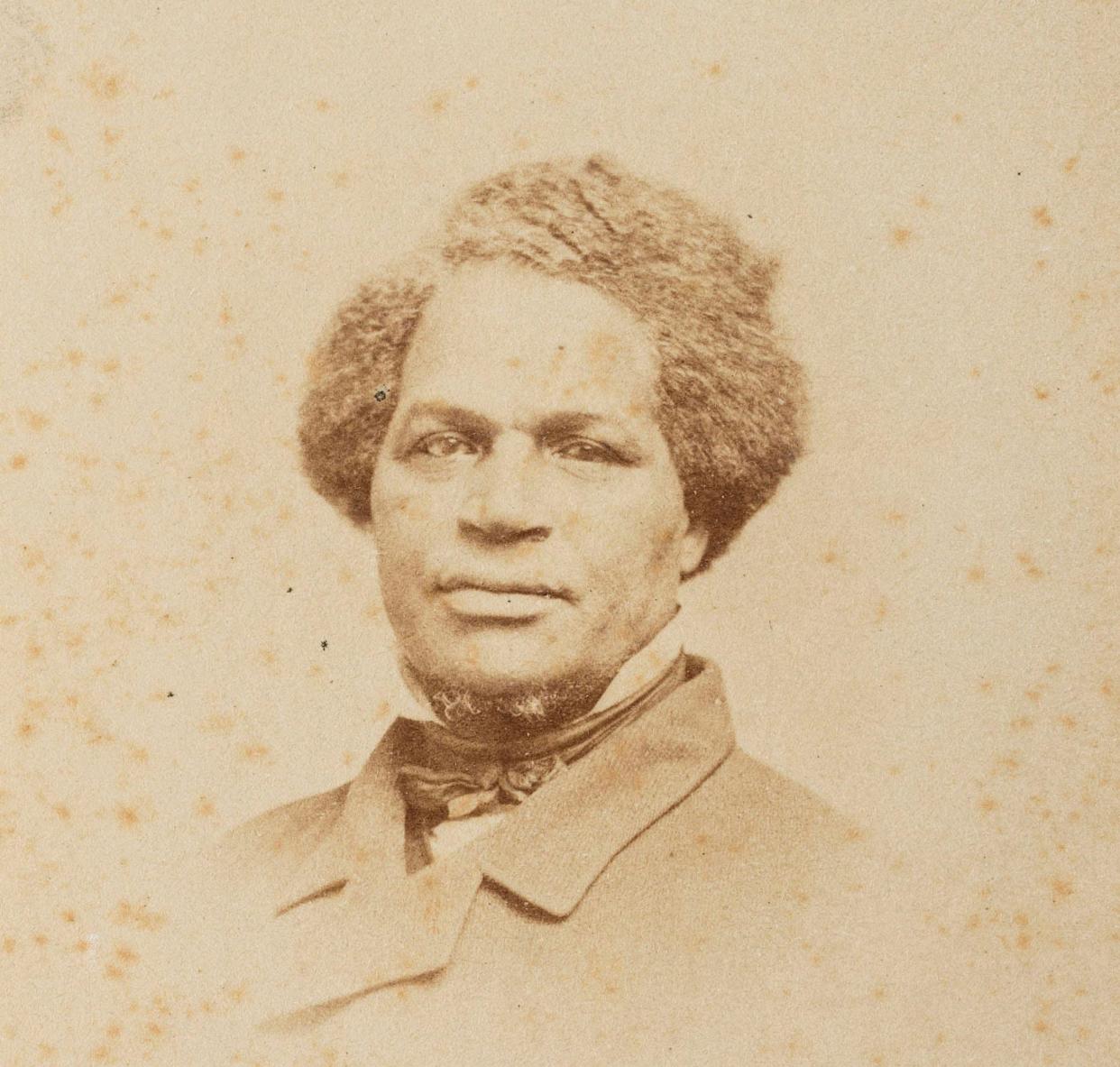

Now, if you search on the internet for his name without reading further, you’re not going to find much because he later changed his name to Jermaine Wesley Loguen. Search that name and you will quickly find an impressive amount of scholarship on a man who became known as the “King of the Underground Railroad.”

So, how did an enslaved man from Maury County, Tennessee manage that? It took an incredible amount of bravery, cleverness and perseverance.

Jarm Logue was born to an enslaved mother named Jane and a White man named David Logue in Davidson County. Jane had been born a free person of color in Ohio, but when still a child was kidnapped and sold into slavery to the Logue family. As a young woman, she became the mistress of one of the Logue sons, David, and together they parented three children. They lived as a family until David eventually married a White woman and sold his Black family to his brother Manassah Logue, who lived in Maury County. Manassah and his wife Sarah appear to have been rather harsh taskmasters to the enslaved on their farm. Jarm, along with his siblings and mother saw the worst aspects of slavery. He also witnessed his mother on numerous occasions show defiance in the face of her enslavement.

The example set by Jane sparked a desire in Jarm, now about 20 years old, to escape and find freedom in the North.

After some time planning and with the help of “a poor white man,” he set out on his journey. Following the advice of his friend, he travelled boldly from town to town staying in nicer establishments and openly carrying a gun. This reverse logic, that no one would suspect a runaway slave to travel in such a manner worked, and Jarm, who then changed his name to Jermaine Loguen, made it to Canada.

Loguen quickly learned that education was the key to his future. After getting a job, he began teaching himself to read. He crossed back into the U.S., and settled in Rochester, New York.

Rochester at the time that Loguen arrived there in the 1830’s, was becoming the center of many reform movements including women’s rights, temperance, and abolitionism. History’s reform giants, Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass, and others called Rochester home.

Jermaine Loguen sought an education first, and was admitted to the Oneida School in 1839, the first college to admit Black students as policy (other, more prestigious schools such as Princeton, admitted “exceptional” Black students only).

He moved to Syracuse, New York, where he followed his second passion, religion. He was ordained by the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church in 1842, and became increasingly associated with the anti-slavery movement. He and Frederick Douglass, also a former slave, became friends and together they traveled the speaking circuit telling their harrowing stories of escape to large crowds.

There was one thing however, that separated Loguen from most other formerly enslaved like Douglass. Although he had the ability to buy his own freedom, as Douglass and others did, Loguen refused. He believed that only God, as creator, had the right to “own” human beings. To buy his freedom would mean acknowledging a man’s right to own another. That was a concept he could never abide. That very deliberate choice had ramifications. It meant that it also precluded him from freeing his mother and siblings who were still held in bondage in Tennessee, and it placed him in grave danger as an outspoken fugitive slave.

In 1850, Congress passed a series of laws in an effort to stave off civil war. One, the Fugitive Slave Law, stated that any person could be deputized and was bound by law to report and apprehend any and all fugitive slaves in the United States. If a deputized person refused, they could be subject to a $1000 fine. All it took for a person to claim a fugitive slave was a signed affidavit. The alleged fugitive slave had no rights in the courts to defend themselves. A judge who heard the case was paid $10 for every fugitive slave sent back into bondage and $5 for every one that was deemed free. Justice has come a long way.

With the passing of the Fugitive Slave Law, Loguen was a marked man. But that fact only emboldened him. He stated “The Fugitive Slave Law outlaws me, and I outlaw it.” He was not the only fugitive slave in Syracuse, and it wasn’t long before an attempt was made.

William McHenry, known as “Jerry,” was captured as a runaway and was placed in jail. Loguen organized a group of vigilantes and broke Jerry out of jail. The “Jerry Rescue” received national coverage and is memorialized today with a statue in Syracuse. Loguen was identified as the ring leader and was charged with murder (although no murder took place) and he was forced to flee to Canada. He wrote several letters to the governor of New York stating that he found it terribly ironic that he had to go to a constitutional monarchy like Canada to find “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Receiving no replies, he moved back to Syracuse, trusting that his neighbors would defend him if needed.

Loguen then took one step further. He actively aided runaway slaves, providing them with food and shelter in his own home.

And when I say actively, I mean he advertised it. Brave. The Underground Railroad was a smuggling operation. It consisted of a series of secret hiding spots and houses stretching from the deep South to Canada, where sympathetic people provided an escapee with food and rest and sent them on their way to the next “depot” or safe house further North.

In order for it to work, it required secrecy. Loguen didn’t care. In an April 1855 issue of "Frederick Douglass' Paper," he wrote, "that the Underground Railroad was never doing a better business than at present. . . . I speak officially, as the agent and keeper of an Underground Railroad Depot." Super brave. It was at this time that he earned the nickname “King of the Underground Railroad.”

Loguen’s fame hit its zenith in 1859 when he published his slave narrative, “The Rev. J. W. Loguen, as a Slave and as a Freeman.” It became a best-seller, and soon, Frederick Douglass was introducing Loguen at public speaking engagements.

Still considered a fugitive slave, it wasn’t long before he received a letter from his former “owner” in Maury County, Sarah Logue, who had likely heard about the autobiography, if not read it herself, where she was mentioned in less-than-glowing terms.

In the letter, she decried how much the farm had suffered since he ran away (some 20 years prior!), that the horse he stole when he left, although reclaimed, was never the same, and that she had been forced to sell Jermaine’s siblings and some acreage to survive.

She proclaimed Loguen unfit for the ministry, calling him a thief (stealing himself as well as the horse, both equally her property, according to slave law) and a liar. She went so far as to accuse him of being ungrateful since the Logues “reared you as we reared our own children.”

Shouldn’t he feel terribly guilty for leaving? All could be remedied if he would send her $1,000, so she could redeem the land she sold (she never mentioned buying back his siblings). If he didn’t, she stated that she had a buyer ready to purchase and retrieve him. There was the threat.

Can you imagine what those words must have felt like to a man like Loguen?

White hot anger might have coursed through his veins with every accusation. To his credit, he kept his cool and wrote an eloquently scathing reply. With his now learned voice, he countered her point-by-point. Of course, the most heart-rending part had to do with the sale of his brother and sister and Sarah Logue’s maternal claim to him. He replied by asking: "did you raise your own children for the market? Did you raise them for the whipping-post? Did you raise them to be drove off in a coffle in chains?"

He ended the letter with this powerful paragraph as follows:

“But you say I am a thief, because I took the old mare along with me. Have you got to learn that I had a better right to the old mare, as you call her, than MANNASSETH LOGUE had to me? Is it a greater sin for me to steal his horse, than it was for him to rob my mother’s cradle and steal me? If he and you infer that I forfeit all my rights to you, shall not I infer that you forfeit all your rights to me? Have you got to learn that human rights are mutual and reciprocal, and if you take my liberty and life, you forfeit your own liberty and life? Before God and High Heaven, is there a law for one man which is not a law for every other man?”

I bet Sarah Logue wasn’t expecting that response. She may have lost a slave named Jarm Logue, but she got “whipped” by Jermaine Loguen.

Both Sarah Logue’s letter and his response were published in newspapers across the country and made Loguen’s star rise even further. It was at this time that Loguen began to get introduced at public speaking engagements by Frederick Douglass, instead of the other way around.

Immediately following the Civil War, Jermaine returned to Maury County to see his mother, who still lived on the Logue place, but once again as she had been born, a free person of color. She recognized him immediately and embraced him. She even got to hear him preach in Columbia. She remained in Maury County for the rest of her days.

After the Civil War, Loguen continued to preach. A number of his churches still stand today in Upstate New York. He became a bishop of the AME Zion denomination in 1868, responsible for the Alleghany and Kentucky Conferences. In 1872, Loguen was about to embark upon a mission to the Pacific Coast when tuberculosis forced him to resign and seek a cure in Saratoga Springs, New York. He died there on September 20, 1872. He was buried in Oakwood Cemetery, in Syracuse.

The story doesn’t end here, of course. His legacy has far outreached his lifespan.

Loguen married Caroline Storum in 1840 and the two had six children. One of his daughters, Helen Amelia, was a noted academic who married Frederick Douglass’ son Lewis, who fought in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry during the Civil War alongside the son of another famous Black Maury Countian, Edmund Kelly. Another daughter, Sarah, graduated from Syracuse University Medical School, making her the fourth Black woman in the U.S. to earn a formal medical degree. She became the first female doctor in the Dominican Republic.

That is quite a legacy for a man who started life with nothing but hope and a dream. It’s perhaps the greatest of American stories, and one more inspirational story that starts right here in Maury County.

Tom Price is director of the Maury County Archives.

This article originally appeared on The Daily Herald: Maury County Hero: Jermain Logue called King of the Underground Railroad