Knock it off with 'Angelino.' People in L.A. are 'Angelenos,' and that's that

Last time in this space, I wrote to begin a civic discussion over what it takes to be an Angeleno.

This time, I’m writing to settle a discussion.

Someone who lives in Los Angeles, city or county, is an Angeleno. Not an Angelino.

Every few years, this topic pops up like dormant insects persistently rising from their hibernation. And so it’s time again to bring out the bug spray and kill off “Angelino,” and even worse contortions of the simple and elegant word for who we are.

What, you say? Live and let live? “Los Angelino” or “Angelean” or “Los Angelean” — whatever?

Nope no non nein não nyet nahi không voch, and ixnay. If you call yourself an “Angelino,” then you must live in a place called “Los Angelis,” wherever that is. The name of the city and county is Los Angeles. Calling an Angeleno an Angelino is like calling a New Yorker a “New Yirker,” a denizen of some imaginary burg called New Yirk.

The word for a resident of a place is “demonym,” and I can be a demonym on this subject.

In this I have the backing of that online arbiter Wikipedia. Look under “Angelino” and you will find “for a resident of Los Angeles, see Angeleno.” And if you prefer old school, the august Encyclopedia Britannica, with more than a quarter-millennium’s worth of candles on its birthday cake, uses “Angeleno.”

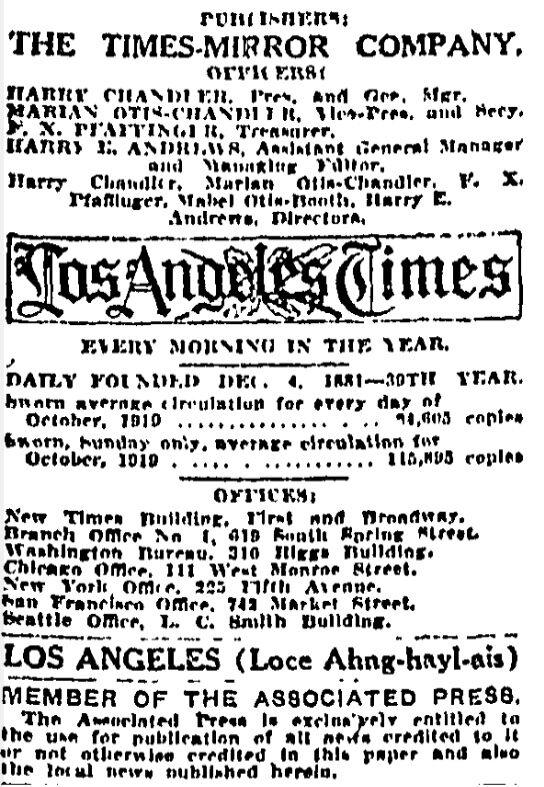

Even just going by the numbers, the “Angelino” faction loses. “Angelino” first appeared in The Times in March of 1887, in a story about new electric lights and smallpox worries, and for more than a century thereafter counted only 300-some citations in news articles. “Angeleno,” however, first appears in January 1882, only a few weeks after the paper began publishing, in a story about agriculture, and enjoyed more than 14,000 news article uses thereafter.

I’ve known Fernando Guerra for a long time. He’s a native Angeleno who’s now a professor of political science, international relations, and Chicana/o Latina/o studies at Loyola Marymount University. For our purposes, he is, more importantly, the director of the university’s Leavey Center for the Study of Los Angeles.

Several times a year, the center commissions studies and surveys, like the one asking L.A. County and city residents whether they consider themselves Angelenos. For years, more than 70% answer “yes.”

In his classes, it’s “not unusual for it to come up when talking to students, and “most of them do say it sounds more natural to be –eno.”

Then why did “Angelino” even get any purchase, I asked him. “This is pure conjecture on my part. I’ve thought about this from time to time, and I’m not really a historian, but my sense was that [people] are ignorant, and that some were doing it to distinguish the new Los Angeles” — the modern-era Anglo L.A. — “from the Spanish or Mexican Los Angeles.”

Slightly off-topic, on the matter of pronunciation, it’s true that in the early decades of the 20th century, the folks who came here from the East and Midwest — among them the city’s Nebraska-born mayor, Sam Yorty — were rather impatient at the notion that they should work to master Spanish pronunciation. Yorty pronounced it nasally, and with a hard-G, “Ang,” like “bang,” “huh-luss.” The Times for years printed a helpful pronouncer on its masthead: “Loce Ahng-hayl-ais.” Yet in 1934, when the U.S. Board of Geographic Names decreed that it be pronounced “Loss An-je-less,” close to the way we do today, The Times said it made us sound like “some brand of fruit preserve” and repeated its own pronouncer as a truly Spanish one.

Not long after Guerra and I spoke, he emailed me: “I just realized that when you do voice to text using your cell or computer, it always spells the word Angelino.” To some software company somewhere — I’d like to have a word.

Bill Deverell, a USC history professor and director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, prefers the -eno version. “I — rightly or wrongly — put the -ino suffix into a ‘from Europe, likely Italy’ point of origin. So I like the borderlands/Mexican ‘eno’ better, while acknowledging that, yes, Spain is also European.”

Angelino Heights is the name of one of the oldest neighborhoods in L.A., crowned by the picturesque Carroll Avenue, a street of absolutely gem-like Victorian-era houses, a street often mobbed by movie and TV crews and the tourists looking for the “real” locations. Its spelling has been much disputed. The development was supposedly originally “Angelino Heights,” but the streetcar destination was “Angeleno Heights.” Into the 1980s, residents were still arguing over the spelling, and the Angeleno Heights Community Organization was throwing an annual Christmas party.

Leo Politi, the L.A. artist and author of delightful children’s books, charmingly illustrated the diverse neighborhoods of L.A., including one he called “Angeleno Heights.” Now, Politi was Italian American, so he of course knew that “Angelino” is Italian.

The correct Spanish pronunciation of “Angeleño” is “Ahn-hell-len-yo,” as dictated by the tilde, the diacritical mark above the second n. The writer D.J. Waldie, my friend and literary idol, has written wistfully about restoring the Spanish pronunciation of “Angeleño,” with the tilde; into the 1860s, he has observed, residents usually spoke at least a bit of each other’s language, and “Angeleños,” with the tilde, is what you likely would have heard.

Guerra thinks that ship has sailed. “It’s too difficult to get people to do that now, especially when there’s no group or movement” pushing for it. It’s not unlike how the locals pronounce “San Pedro” as “San Peedro.” “The ownership in that neighborhood, when they took that word — the people who live in San Pedro, including Latinos, are talking about that specific place, and they would have no problem going to San Pedro in Mexico and saying ‘San Pedro.’”

You may have noticed that Guerra’s professorship encompasses Latina/Latino and Chicana/Chicano. But he laughed when I said I thought that saying “Angelena” for an L.A. woman can be more confusing than illuminating. (Not that I’d object to being confused with the homonymic “Angelina Jolie,” but to add yet more confusion, it sounds more like what it means when it’s pronounced with the tilde, “Angeleña,” rather than without.)

Billy Joel kind of waded into this about 50 years ago. He lived briefly in L.A. and left us a song: “Los Angelenos.” He hit the high points, that we “all come from somewhere/to live in sunshine/their funky exile,” and about the colonies of the canyons and hillsides.

But “Los Angelenos” — “The Angelenos” — is not usually what we call ourselves. We call it “the Sunset Strip” and “the 405 Freeway,” but rarely “Los Angelenos.” To say “I am a Los Angeleno” means roughly “I am a the Angeleno,” “Los” indicating a plural, to make it even more confusing.

The redundancy of “the La Brea Tar Pits” is a charming local quirk — “the the tar tar pits.” But “I am a the Angeleno” sounds both befuddled and messianic.

Still, Angelenos can count ourselves fortunate. The residents of nearly 90 cities in Los Angeles County are burdened with some odd demonyms: Monterey Parkers, San Dimasans, Hidden Hillers, Hawaiian Gardeners, Walnutters.

We could amuse ourselves by starting a branding campaign for residents of neighborhoods within the city of LA. Eagle Rockers? Carthay Circlers? Mar Vistans?

People in Venice are properly Venetians, but they so pride themselves on being orbitally apart that perhaps they’d prefer to be Venusians.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.