What we know about the investigation into Native American boarding schools

A landmark federal report published earlier this month offers the first extensive review of the government-operated boarding schools for Native American children. The schools operated for more than 150 years and imparted a traumatic legacy.

The boarding schools report was the result of an 11-month investigation launched by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. She's pledged to keep digging.

This issue is not new to Indigenous people who live with the legacy trauma of federal Indian boarding school policies. What is new is the determination of this Administration to make a lasting difference in the impact of this trauma on future generations. https://t.co/0nQhtess96

— Secretary Deb Haaland (@SecDebHaaland) May 12, 2022

What did the Interior Department find in its investigation of Native American boarding schools?

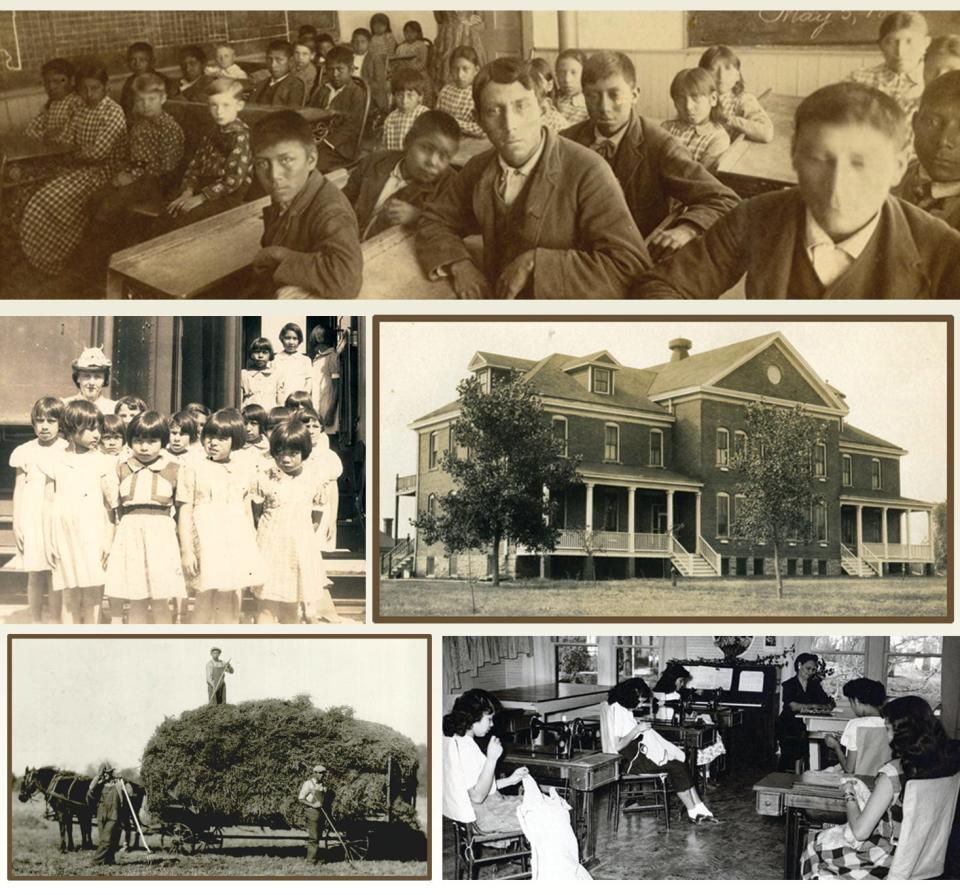

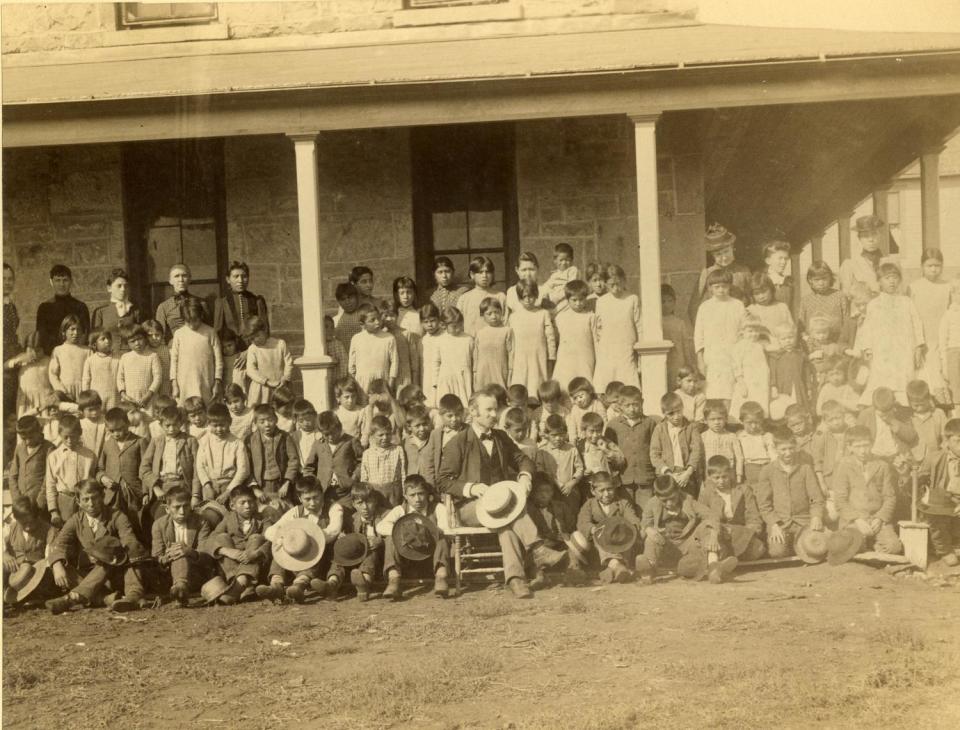

The investigation determined the United States government forced generations of Native American children attend boarding schools for two reasons: to assimilate Native Americans into white culture and to claim tribal land for the country's westward expansion.

The schools weren't focused on education. Native students were often abused and forced to do heavy labor and military drills. School leaders changed children’s names, cut their hair, forbid them from practicing any part of their cultures and handed down severe punishments for speaking Indigenous languages.

The lasting trauma from the boarding school era still impacts Native communities today. It has direct ties to high rates of violence, poverty, mental health disorders and substance abuse, the Interior Department investigation confirmed.

MORE: Native leaders press Congress for formal commission to investigate boarding school traumas

How extensive was the federal investigation?

Federal officials began sifting through hundreds of years of government records in June. They ultimately found evidence that the U.S. government backed 405 boarding schools for Native American children. Dozens of the schools were in Oklahoma and Arizona, two states with particularly large Native American populations.

Religious groups such as churches operated many of the schools. Congress passed a law in 1819 to pay churches to operate the schools and “civilize” Native children.

Some religious institutions for Native American children operated without federal funding. Those schools aren't part of the federal investigation. The full report from the investigation is available online.

How many Native American children died while attending boarding schools?

No one knows how many Native American children may have died while attending schools away from home, but federal officials say they are still trying to find out. They expect to find records of thousands or tens of thousands of child deaths at the schools.

Officials have so far documented 53 burial sites on boarding school grounds. A similar review is being conducted in Canada, where researchers have uncovered mass burial sites of Native children near former boarding schools.

'Whose daughter is next?' Native families, supporters rally for missing, murdered Indigenous people

Where were Native American boarding schools located in Oklahoma?

The federal government paid the bills of 76 boarding schools for Native American children in Oklahoma.

Most of the schools first opened their doors when the region was known as Indian Territory. The U.S. government forced dozens of tribes from across the U.S. to leave their homelands and relocate to the region. Boarding schools opened around the relocated tribes, concentrating in the eastern half of present-day Oklahoma.

The schools also took in children from as far away as Alaska. Some children born into tribes based in Oklahoma were also sent far from home to schools in other states, including Kansas, Nebraska and Pennsylvania.

Who ran boarding schools for Native American children in Oklahoma?

Boarding schools were often operated by religious groups, including the Catholic, Methodist Episcopal, Mennonite, Presbyterian and Quaker churches. They received funding from the federal government. The Interior Department investigation found evidence that some school bills were paid with money that was supposed to compensate tribes for ceding their homelands.

The United States also operated some of the schools on its own. One of the largest was Chilocco Indian School in Newkirk in north central Oklahoma. It housed Native children from all over the U.S. Its operations were modeled after Carlisle Indian School, a Pennsylvania school notorious for its military-like conditions.

It wasn't uncommon for ownership of the schools to change hands over time, particularly in eastern Oklahoma. The Five Tribes took over responsibility for many of the schools on their respective reservations around the late 1800s and early 1900s, according to the federal report. But some of the schools later returned to outside operators as the U.S. government pursued a campaign of breaking up tribal governments and nations.

Some Oklahoma boarding schools were segregated and enrolled only the children and descendants of freedmen, African Americans who had been enslaved by one of the Five Tribes before gaining freedom in 1866.

Although nearly all of the boarding schools in Oklahoma are now shuttered, some of the buildings are still standing. Some are used today for different purposes by tribes. Others sit empty.

How long did boarding schools to assimilate Native American children exist?

Boarding schools designed to assimilate Native children into mainstream society operated throughout most of the 1800s and 1900s, until at least 1969.

The United States still pays for the education of Native American children as part of its trust responsibility to tribal nations. It also operates four off-reservation boarding schools, including Riverside Indian School in Anadarko. But federal officials maintain that there is a clear divide between the schools of the past and those open today.

“The difference is at the core of the schools’ mission, which is to empower Indian kids in their communities, to attempt to revitalize languages and cultural practices and not to forcibly assimilate kids and not to take them from their families without their consent,” said Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Brian Newland.

$1 billion gap: Boost for Native American health care left out of federal spending bill

What's next for the Interior Department's review of Native American boarding schools?

Interior Department leaders plan to keep investigating both the direct harm and lasting damage of boarding schools. Congress approved $7 million to continue the review. Some focus areas will include counting all the children who attended the schools and all the children who died while attending them. They also plan to account for all the federal money spent on the schools.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland will meet with boarding school survivors throughout the U.S. over the next year. She wants to help create a federal repository of oral histories detailing what people experienced at boarding schools.

Will Congress expand the investigation into Native American boarding schools?

Some U.S. lawmakers want to pass a bill that would establish a formal truth and healing commission to investigate the boarding school era. The commission would have the power to subpoena churches to turn over their boarding school records. After meeting for five years, the panel would report on its findings and recommend steps the government could take to help Native communities recover.

The proposal received its first hearing last week before a House subcommittee. Speaking at the hearing, House Natural Resources Committee Chair Raúl M. Grijalva, D-Arizona, described the proposed commission as crucial.

But the proposal hasn't drawn much support from Republicans. Only six have so far signed on as co-sponsors. Two Oklahoma congressmen, Reps. Tom Cole and Markwayne Mullin, are among them. Cole belongs to the Chickasaw Nation, and Mullin belongs to the Cherokee Nation.

Boarding school survivors who want to submit testimony regarding the proposed commission can email the House Natural Resources Subcommittee for Indigenous People through May 26 at hnrcdocs@mail.house.gov.

What support exists for survivors of Native American boarding schools and their families?

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition formed in 2011 to increase awareness about the boarding school era. The group is currently organizing support for the proposed federal commission to investigate what happened.

The coalition also works to bring together survivors, their families and tribal leaders to promote healing. Its website is boardingschoolhealing.org.

Molly Young covers Indigenous affairs for the USA Today Network's Sunbelt Region. Reach her at mollyyoung@gannett.com or 405-347-3534.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: What to know: Federal report on Native American boarding schools