What to know about Kevin Strickland and his 40-year fight for freedom

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On Tuesday a Missouri judge agreed with Kevin Strickland’s lawyers, ruling after three days of evidentiary hearings that he should be set free.

Strickland spent more than 40 years in prison for a triple murder in Kansas City that he and local prosecutors have maintained he did not commit.

He has tried by himself, at least 17 times, to get his claims heard. Before now, he had never received a hearing.

Since he was sentenced in June 1979, Strickland has spent 42 years, 4 months and 11 days in Missouri prisons.

That’s 15,474 days total.

The 40-plus years that Strickland served in Missouri prisons is one of the longest wrongful imprisonments acknowledged in U.S. history, and by far the longest in Missouri.

Strickland’s case and his fight for freedom have received national attention. Here, we answer some of your questions about him.

Who is Kevin Strickland?

Kevin Strickland, 18 at the time, was living with his family at 5540 Jackson Ave. in Kansas City when he was arrested.

He had dropped out of Southeast High School and recalled that he recently applied to join the military. He figured he could see the world and marry his girlfriend that way. He was also the father of a 7-week-old daughter.

Strickland has maintained his innocence in the April 25, 1978, shooting at 6934 S. Benton Ave. that left 20-year-old John Walker, 22-year-old Sherrie Black and 21-year-old Larry Ingram dead. A fourth victim, the only eyewitness to the crime, was wounded.

Now 62, Strickland has said he was at home during the murders, watching TV and talking on the phone to his girlfriend. The only eyewitness to the killings later recanted her testimony, saying Strickland had been wrongly charged, her relatives say.

He was released from prison in Cameron, Missouri.

How did he end up in prison?

The most damning evidence against Strickland came from the lone eyewitness, 20-year-old Cynthia Douglas.

At trial, Douglas said there was “no question” Strickland was one of the four gunmen.

On the night of the killings, she told police she could only identify two of the four suspects: Vincent Bell and Kilm Adkins. She identified Strickland the next day after she described a shotgun-wielding suspect to her sister’s boyfriend, who suggested that perpetrator might be Strickland.

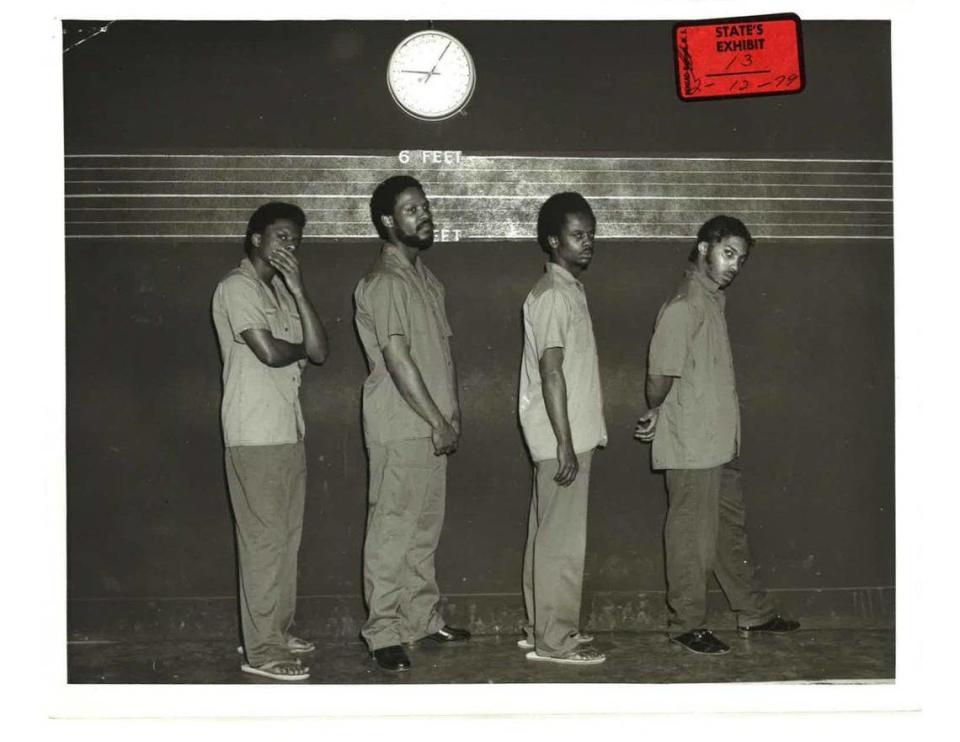

Strickland’s first trial in 1979 ended in a hung jury of 11 to one, with the only Black juror holding out for acquittal. He was later convicted by an all-white jury of one count of capital murder and two counts of second-degree murder.

He became the first Jackson County defendant sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for 50 years.

Douglas later recanted her testimony, Baker’s office said. In 2009, Douglas wrote an email to the Midwest Innocence Project saying she wanted to help Strickland, who she described as having been “wrongfully charged.”

“I am seeking info on how to help someone that was wrongfully accused,” Douglas wrote. “I was the only eyewitness and things were not clear back then, but now I know more and would like to help this person if I can.”

Who argued he is innocent?

In an investigation published in September 2020, The Star reported that, for decades, Bell and Adkins — both of whom pleaded guilty in the killings — swore Strickland was not with them and two other accomplices during the shooting.

“I know because I’m one of the ones who did it, God forgive me,” Bell told The Star.

In 2019, Terry Abbott, a third suspect who was never charged, told an investigator with the Midwest Innocence Project that he knew Strickland was innocent. In an affidavit, the investigator said Abbott — who is doing time for a robbery in Colorado — told her there “couldn’t be a more innocent person” than Strickland, who went by the nickname Nordy.

“Terry returned to saying this many times throughout our long conversation, repeating that Nordy is innocent and that there is no way that Nordy would do something like this,” the investigator, Blair Johnson, wrote.

Douglas, the eyewitness who recanted, also told relatives she wanted nothing more than to see Strickland freed.

After a months-long review, the Jackson County Prosecutor’s Office in May said it had determined Strickland is “factually innocent.” The region’s top prosecutors called for his exoneration and immediate release.

Additionally, federal prosecutors in western Missouri, Jackson County’s presiding judge, Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas and members of the team that convicted Strickland four decades ago now all agree he deserves to be exonerated.

St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Wesley Bell also agrees that the evidence supporting that Strickland was wrongly convicted “is overwhelming.”

Earlier this year, 13 state lawmakers called on Gov. Mike Parson to pardon Strickland. Kansas City’s City Council also passed a resolution urging Parson to pardon him. Parson, though, has said he is not convinced Strickland is innocent.

In September, Edward “Chip” Robertson, who served on the state Supreme Court for 13 years, joined Baker’s efforts to free Strickland.

Why did it take more than 40 years?

Though Baker called for Strickland’s release in May, prosecutors in Missouri had no legal tools to seek to free prisoners they deemed innocent. That changed Aug. 28, when a new law went into effect allowing her to file a motion asking a judge to exonerate him.

Supporters of Strickland thought he would be freed not long after.

But post-conviction attorneys and legal observers across the state say while the new law is a step in the right direction, it has not worked as effectively as they had hoped, mostly because of intervention by the Missouri Attorney General’s Office.

The attorney general’s office, which contends Strickland is guilty and got a fair trial, is “abusing” the process by filing “motion after motion,” according to Senate Minority Leader John Rizzo, who wrote the provision in the law.

In May, Strickland’s attorneys initially filed his petition in the state Supreme Court, which declined to hear it.

They refiled in DeKalb County, where he remains imprisoned, and got an Aug. 12 evidentiary hearing. But that was pushed to Nov. 17.

His lawyers dropped that case to focus on the one in Jackson County, where a previous evidentiary hearing date was set for Sept. 2. That has been delayed twice due to intervention by Attorney General Eric Schmitt’s office.