What we know now about the rash of whale deaths at the Jersey Shore

A surge of whale deaths along the New Jersey coast has scientists concerned, activists riled and politicians pointing fingers.

Seven whales have been found dead in New Jersey since December. On Monday, in Lido Beach, NY — about 25 miles from New Jersey — an adult humpback whale washed ashore.

Some environmental groups, and a growing chorus of mainly Republican politicians, are blaming the whale deaths on pre-construction work for offshore wind farms. Federal scientists say there is no evidence of this.

Here’s what we know about what’s happening.

When did the whales die?

When whales die in the ocean, many are consumed by scavengers or sink to the sea floor before their deaths can be discovered. However, since 2016, researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, said humpback whales and North Atlantic right whales are dying in higher than typical numbers along the East Coast.

In New Jersey, the agency has recorded four humpback whale deaths so far this year. In December, another two humpbacks and a sperm whale washed ashore New Jersey beaches.

Dec. 5: An infant sperm whale stranded and died in Keansburg.

Dec. 10: A 30-foot humpback whale washed ashore in Strathmere, Upper Township.

Dec. 23: A 30-foot juvenile humpback washed ashore in Atlantic City.

Jan. 7: A 33.5-feet long, female humpback washed ashore in Atlantic City, near Florida Avenue.

Jan. 12: A 32-foot female humpback washed ashore in Brigantine, Atlantic County.

Jan. 18: A dead humpback was seen floating roughly 52 miles off Brigantine, according to NOAA.

Jan. 28: A dead humpback was seen floating about 12 miles off of Long Beach Island, according to NOAA.

In Lido Beach, the roughly 40-year-old male that washed ashore Monday appears to have died as the result of a ship strike, according to NOAA. It was not clear if that whale was the same as one of the dead whales seen floating off New Jersey earlier in the month, NOAA said.

Why are the whales dying?

This is a more complicated question.

The Marine Mammal Stranding Center of Brigantine said the whale that washed ashore in Brigantine had "suffered blunt trauma injuries consistent with those from a vessel strike." A whale that washed ashore in early January in Atlantic City showed signs it had collided with a boat, according to the center.

Stranding Center staff said a large number of whales were feeding close to the coast, which could explain an increase in reports of deaths.

Between 2016 and 2023, NOAA reported unusually high death rates in both humpback whales and North Atlantic right whales.

The federal agency recorded 180 humpback whale deaths over that more-than seven-year period. Of those, about half were necropsied, while the remainder were too decomposed to thoroughly examine, according to NOAA. Of the whales examined, about 40% showed obvious signs of human interaction prior to death, either through evidence of vessel strikes or entanglement with fishing gear, according to the agency.

Between 2017 and 2023, 35 North Atlantic right whale deaths were recorded by NOAA, or about 10% of the animals' population. Of those deaths, 20 were attributed to ship strikes or entanglements fishing gear, according to the agency.

But not everyone is convinced the most recent surge is attributable to vessel strikes and fishing equipment alone.

Why are some people blaming wind development?

Clean Ocean Action, a Long Branch-based environmental organization, called for a moratorium on all offshore wind development activity until the whale deaths are investigated. They've attracted more allies recently. Cindy Zipf, the organization's executive director, is worried that noise from seafloor mapping and soil boring could be behind the whale's deaths.

"The death of seven whales in 39 days is unprecedented," said Zipf in a statement earlier this year. "They were all endangered species, which makes these deaths even more tragic and demands an immediate comprehensive investigative response."

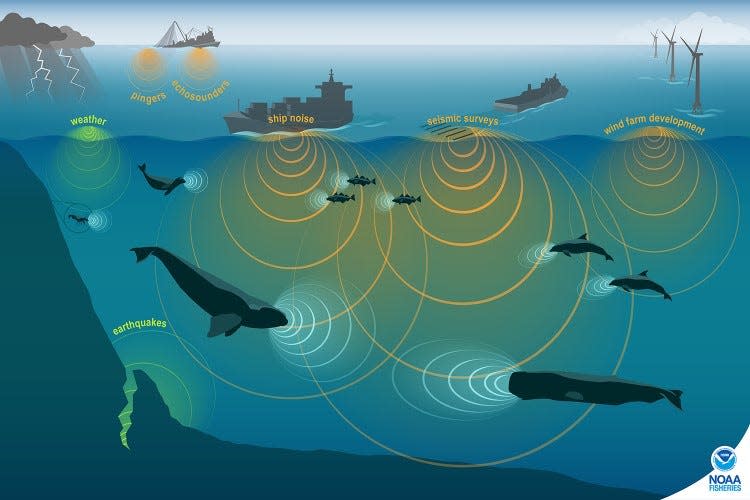

Humpbacks and other whales use sound to communicate, hunt, find mates and navigate. Yet ocean noise from human activity can alter whale behavior, stress the animals, and in some cases, cause disorientation or hearing loss, according to NOAA. Ocean noise can also disrupt nursing mothers and infants as well as push whales away from feeding areas, according to the agency.

Zipf contends offshore wind activity is bringing "more ships and vessels in the area which increase potential ship strikes, and sonar can deafen or disorient whales, leading them into the path of oncoming vessels," she said. "Why shouldn’t endangered species get precautionary treatment and trigger a full investigation?"

NOAA scientists have said there is no evidence that sonar and noise created from pre-construction offshore wind activity is harming the whales.

No whale strandings have ever been documented from offshore wind development noise, Benjamin Laws, deputy chief for the permits and conservation division at NOAA's Fisheries Office of Protected Resources, said last month.

In addition, some of the sound generated by human activity and seafloor mapping equipment cannot be heard by large whales like humpbacks, who hear in lower frequencies than other species, according to Erica Staaterman, a bioacoustician at the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management's Center for Marine Acoustics who talked with reporters last month.

Who's involved with this?

No one is arguing the whale deaths are a good thing, but federal scientists, environmentalists, local Republicans and state Democrats are all particularly riled up about the issue.

Scientists at NOAA have been studying the issue since 2016, when an unusually large number of humpback whales began dying on the Mid-Atlantic coast.

Clean Ocean Action has historically opposed loud underwater surveying that could harm whales and other marine life, and has been among the loudest voices in recent weeks.

This week, Reps. Chris Smith and Jeff Van Drew, two Republicans who represent New Jersey in Congress, and 12 mainly Republican Jersey Shore mayors joined the call for an offshore wind moratorium until the whale deaths are investigated.

Gov. Phil Murphy has declined to pause any offshore wind activity, citing a lack of evidence it is the cause of the deaths.

The issue has created strange bedfellows and pitted some environmentalist groups against one another. Clean Water Action, Environment New Jersey, the Sierra Club, New Jersey Audubon, NY/NJ Baykeeper and others issued a joint statement supporting the wind projects.

"While I am deeply concerned with the recent whale strandings, I also know we must base our decision making on science and data, not emotions or assumptions," Allison McLeod, policy director at the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters said last month. "It is therefore irresponsible to assign blame to offshore wind energy development without supporting evidence."

What is being done?

NOAA officials, in conjunction with marine mammal experts and conservation organizations, are investigating the whale deaths around the country. Vessel strikes and fishing gear entanglement remain the greatest threat to whales, according to the agency.

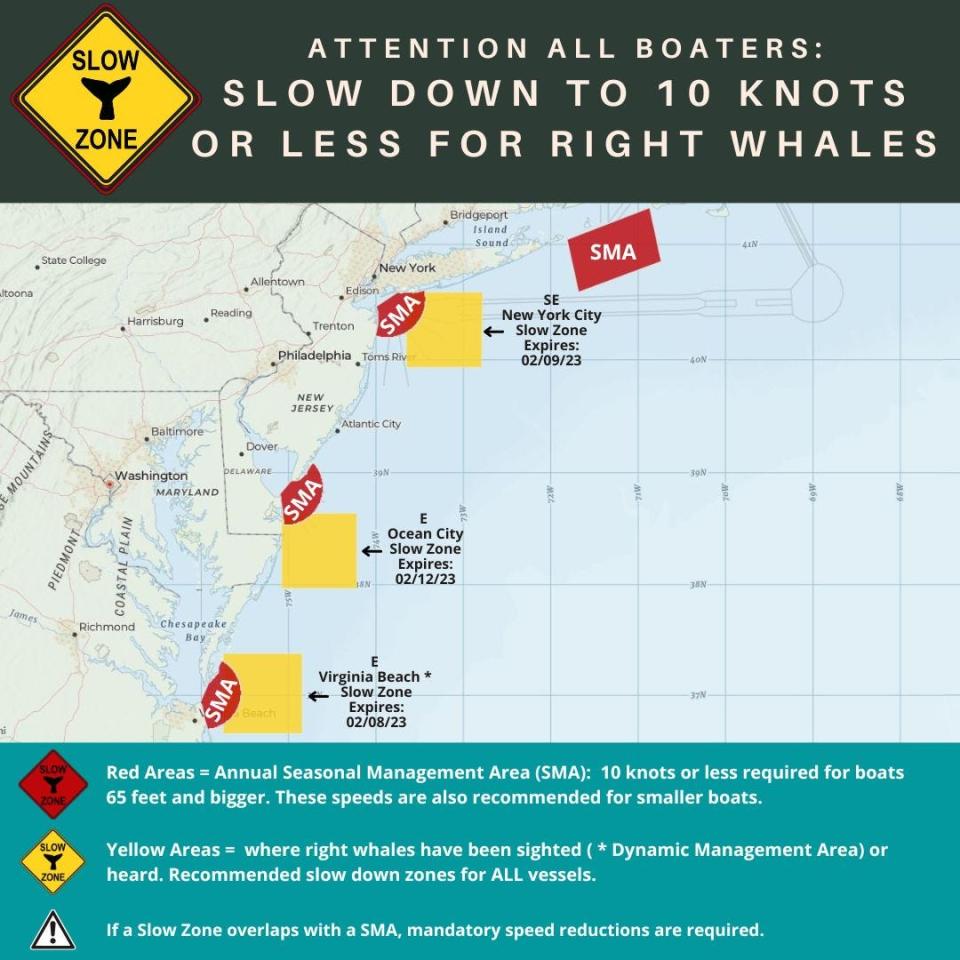

To reduce whale deaths, NOAA urges boaters off New Jersey and New York to voluntarily slow their vessels to help protect whales that are feeding along the coast.

The 10-knot or less speed limit is mandatory for boats 65 feet long or longer in Mid-Atlantic Seasonal Management Areas around Cape May and Raritan Bay through April 30, in order to protect North Atlantic right whales. The areas are important calving and migration routes for the species, according to NOAA.

The speed limit is voluntary, but strongly encouraged, for boats less than 65 feet.

New Jersey's environment:After whale deaths, Rep. Chris Smith joins chorus of calls for offshore wind moratorium

Contributing: Dinah Voyles Pulver, USA TODAY.

Amanda Oglesby is an Ocean County native who covers Brick, Barnegat and Lacey townships as well as the environment. She has worked for the Press for more than a decade. Reach her at @OglesbyAPP, aoglesby@gannettnj.com or 732-557-5701.

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: NJ whale deaths: What we know about rash of strandings on Mid-Atlantic