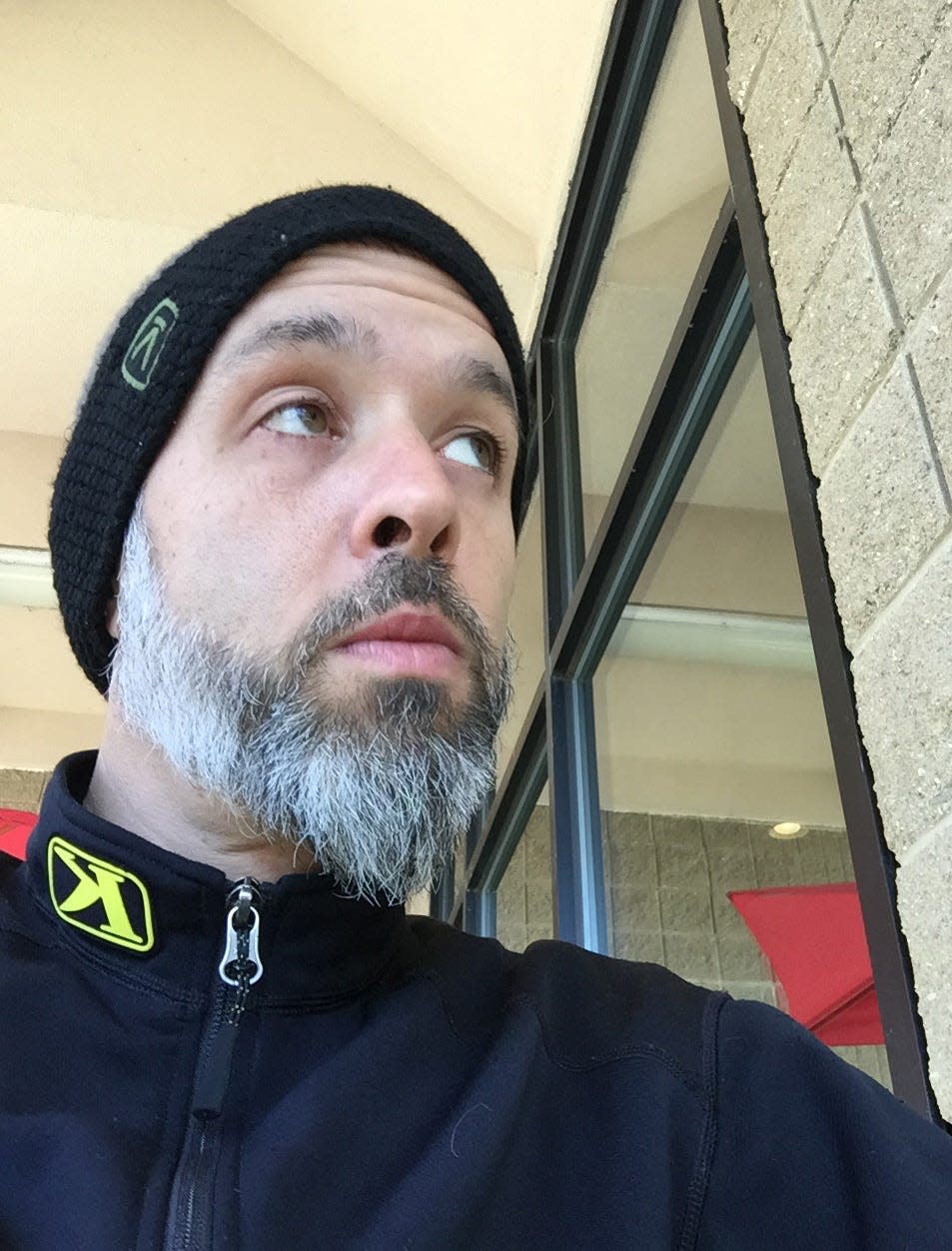

Kurtis Minder has been inside ransomware deals. Here's what he thinks HSHS is up against

Kurtis Minder has been on the inside of cybersecurity and ransomware negotiations.

He has traversed the dark web and visited so-called "shame sites."

He knows the hostage takers, groups like Rhysida, Phobos, Vice Society and Lock Bit, their tactics and operations.

The Chatham native and the chief executive officer and co-founder of GroupSense, which provides businesses digital protection in addition to negotiations, is in a unique position to understand what has happened to Springfield-based Hospital Sisters Health System, the target of "a cybersecurity incident" in late August.

The outage has crippled the not-for-profit Catholic healthcare company's clinical, administrative and communications systems, reducing it to a pen-and-paper operation in some instances.

HSHS hasn't publicly indicated whether patient medical records have been compromised by the attack or whether a senior vice president and chief financial officer was out of a job because of the fallout, though on Tuesday it reported functionality was restored to its electronic health records platform.

Few sectors are immune. On Sunday, over a dozen MGM Hotels & Casinos had to shutter operations after a cyberattack on its computer systems.

Despite knowing some of the information technology workers at HSHS and GroupSense having several employees in Springfield, the 46-year-old Minder, based in Grand Junction, Colorado, and the subject of a 2021 New Yorker article, said his phone hasn't rung for his services.

Minder told The State Journal-Register last week he suspected a ransomware situation has hit HSHS, deducing that if a typical cybersecurity attack is to break in and steal intellectual property or health information data, the bad actors would do that and not disrupt operations.

Despite hacker groups' sophisticated claims, more than likely, he added, HSHS was attacked by a "phishing campaign," where an employee clicked on an attachment in an innocuous-looking email.

Through some independent investigation, Minder thought HSHS or a hired third party had been talking to the trespasser and that so far, no ransom had been paid.

"I sure hope they're engaging a professional," Minder said, "because this is not something you want to do on your own. It can get pretty messy if you do it wrong."

'It only takes one'

Healthcare centers and hospitals have become high-value targets and with good reason, Minder said.

According to the cybersecurity firm Recorded Future, there have been at least 300 documented attacks a year on American healthcare facilities since 2020.

Last month, Prospect Medical Holdings, based in California with hospitals and clinics there and in Texas, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Pennsylvania, was the target of a high-profile ransomware attack by the extortion group Rhysida. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a security bulletin warning last month that the group was behind several recent attacks on healthcare organizations.

Such breaches can be financially painful. IBM's "Cost of A Data Breach Report" found the average cost of a healthcare breach reached nearly $11 million in 2023 – a 53% increase since 2020.

Minder said healthcare information has significant value on underground marketplaces. Health identifiable information, or HII, has a glut of information -- addresses, phone numbers, credit cards and private health information -- all in one place.

Even if groups aren't able to wrestle payment from institutions, they can still recoup value from the stolen information from other industries.

There are other reasons groups prey on healthcare institutions, he added.

"Healthcare as an industry has been a little bit slower to catch up to adopting a lot of the cybersecurity best practices," Minder said. "I'm not saying that punitively because their environments are extremely complicated."

Inside a facility like HSHS St. John's Hospital, the largest of the 15 that make up the system, specialized devices often are managed by third parties, he pointed out. For example, the radiology imaging system may be managed by one company, while the fetal monitoring system is looked after by another.

The initial foray might be difficult for the bad actors to mitigate because the system isn't being immediately managed by the targeted healthcare institution, but it ultimately could be the portal to the network where all other systems exist, including the electronic medical records system.

"It only takes one for that to unravel quickly," Minder said. "Once the bad guys get access to a single system on a domain, they can actually get access to all of the other systems by reading the credential information and memory on that system."

The healthcare industry has been spread thin since COVID, he added. There's a lack of resources and a complex environment to secure, and IT security budgets "haven't caught up to normal industry levels."

The 'business' of hacking

Criminal syndicates typically are behind most ransomware attacks and the handful of groups are mostly out of Russia or Russian-influenced states, like Moldova, Belarus, and parts of Ukraine, Minder said. A couple are in South America and China, while others are in Iran and North Korea, he said.

In the last few months, though, there has been upheaval among the ransomware groups. The code the 20 or so primary groups used to conduct the attacks was leaked -- that's right, the bad actors' code was leaked -- and now unknown individual actors or small groups are wreaking havoc.

That poses problems for Minder's group and potentially companies such as HSHS.

Groups like Rhysida or Lock Bit typically announced themselves in ransom notes and there was a familiarity to the extent that if there were problems with the decryption key to unlock the hijacked files at the end of the transaction, the groups would give technical support "as if they're Dell," Minder said.

But if rogue groups are paid and the decryption key doesn't work, "you're screwed," Minder said.

The larger ransomware groups are effectively running a business with, he said, "employees and middle management and quotas." There's "brand reputation," the idea that groups honor ransom payments and unlock files as part of the agreement.

They even profit from sharing their ransomware platform with "affiliates."

While the masterminds who run the larger groups may be in Russia, Minder's group found affiliates doing operations all over, "so it's not impossible (the HSHS attack) was an affiliate attack and these people could be anywhere," he said.

'Shaming' victims

Minder's group is typically brought into a ransomware case by cybersecurity insurance companies or law firms who have a cyber practice representing the trespassed company.

The first step usually is to help assess the impact of the attack on the victim's business "as quantitatively as possible," Minder said.

In some cases, businesses may not be able to legally or ethically engage with groups.

"We help them make a decision," Minder said. Then, it's figuring out what it is worth to pay.

"Sometimes these guys are not very cooperative and they're asking for ridiculous amounts of money, but a lot of times we can negotiate them down considerably so we know what the range of success might be," he said.

There's an "art form" to the negotiations -- more of a business transaction than anything, he said -- which is one of the advantages of bringing in a third party.

"Shame sites" are set up by most of the groups, places on the dark web where organizations not cooperating with or not engaging with the hackers are outed. Minder said he visited the known sites and did not find HSHS listed.

The majority of ransomware companies use a dark web chat room for negotiations and give the negotiator an ".onion" address, meaning the conversation can't be followed, Minder said. Others simply use email, he added.

Once a virtual handshake is made, "you want to be making a payment to them (in short time)," Minder said. His group would ordinarily work with the victim's finance organization to figure out the most efficient way to get traditional capital into a crypto format.

Minder said he wasn't surprised "federal law enforcement" was involved in the HSHS matter -- the Springfield FBI office wouldn't confirm or deny the agency was investigating -- because he has worked with FBI officials on behalf of the victims in the past.

"The DOJ's official stance is you should not pay the ransom, but the FBI is not running a business," Minder said. "What they're not going to tell you is that it's not illegal to pay it and most people do it and we're not going to stop you."

'A national security issue'

The motorcycle-riding Minder, whose parents and sister live in Rochester, is judicious in his mannerisms, apt for his role as a sometimes-negotiator.

What gets him revved up, though, is the lack of what the U.S. government is doing to prevent ransomware attacks.

"What's occurring here," Minder said, "is that we have foreign actors who are given amnesty from their own country, Russia for example, who are causing deliberate operational and monetary harm to our companies in the U.S. every single day, to the tune of millions and millions of damages and/or ransom payments, and I'm a little bit upset that the U.S. government isn't doing more about it.

"The metaphor I use is that if Russian soldiers parachuted into Microsoft's campus in Seattle and started storming the building, the U.S. government would send the Navy Seals down there. Digitally, they show up on Microsoft's campus and everybody else's campus every single day and the U.S. government says, 'Good luck fighting Russia, guys.' I believe it's a national security issue.

"If we're not paying attention (to this), and we aren't, it will be death by a thousand cuts, economically and for our jobs, and I'm upset about it."

The National Health Information Sharing & Analysis Center, which is a nonprofit organization that provides cybersecurity-related intelligence information to hospital members, recently wrote specifically about Rhysida, even pointing out the tools it was using to attack healthcare institutions.

"I'm not saying HSHS ignored those things," Minder cautioned, "but it is well known that there are at least one or two ransomware groups that are targeting healthcare institutions and we kind of know how they do it. That's good information if you're going to defend yourself."

On a more general scale, a majority of companies are below what Minder called "the cybersecurity poverty line. Without IT security personnel on staff, they're sitting ducks (for ransomware companies)."

It's a common outcome, Minder said, for companies, especially smaller players, to shut down because it doesn't make financial sense to rebuild.

And it's hit close to home.

A ransomware attack was a big reason why Lincoln College, a federally recognized predominantly Black institution whose founding dated back to the end of the Civil War, was shuttered last spring.

St. Margaret's Health in Spring Valley, Illinois, two hours northeast of Springfield, closed in June for several reasons, including a debilitating ransomware attack.

Kelly Barbeau, the marketing and communications director for HSHS Illinois, said it is making "significant progress."

"We continue to bring systems back online following a careful validation process with our third-party experts," Barbeau said through email. "HSHS colleagues have been working around the clock to restore systems, prioritizing clinical applications as part of our relentless focus on safely caring for our patients.

"We remain focused on restoring remaining affected systems, including business applications, in a methodical and thoughtful manner, which will take time to complete."

The situation has heightened the attention of the rest of the medical community in Springfield.

Zach Kerker, vice president of brand experience and advocacy for Springfield Clinic, said safeguarding patients' personal and private information is "a responsibility we take incredibly seriously, especially as healthcare has become a target of attacks.

"Cybersecurity is at the forefront of everything we do at Springfield Clinic and while no one is entirely immune, we have systems and strategies in place to protect against these attacks," added Kerker, in a statement provided to The State Journal-Register.

Angie Muhs, a manager for strategic communications at Memorial Health, said the Springfield-based system treats cybersecurity and patient safety as a matter of "paramount importance."

"While we cannot discuss specific protocols due to security concerns, our organization has consistently and continues to utilize rigorous safeguards to protect our networks," she added, via an emailed statement.

Springfield Mayor Misty Buscher said she reached out to HSHS president and chief executive officer Damond W. Boatwright to say the city is ready to help.

"Quite frankly, those who are trying to hack into any of our systems are all over, everywhere, so we need to support each other when those things happen," Buscher said. "We all hire agencies to test our firewalls, but again there are people out trying to do bad things and sometimes it happens."

The frustrating thing for Minder: the bad actors are doing basic attacks that are preventable with some cyber hygiene basics.

Those include restricting access to personal email on company assets; maintaining and publishing a password policy for the organization; enabling multi-factor authentication capability on work email, network access and remote access, and investing in cyber insurance.

HSHS has indicated that if any patients' sensitive or personal information was compromised, it would notify them "in accordance with applicable law." Illinois law requires certain businesses and state government agencies that experience a data security breach to provide notice to the Attorney General’s Office in addition to providing breach notification to affected Illinois residents.

That's little consolation to Minder.

"Whether it's health care or anyone who has your personal information, you've allowed them to be a steward, a custodian of your data, and once they've screwed that up, there's not a lot you can do to remediate that," he said. "You're basically collateral damage."

How could this end up for HSHS? Considering how long it's been, Minder speculated HSHS was probably trying to restore its systems without paying the ransom because otherwise, "I think they probably would've come to a settlement by now. Maybe one of the scenarios is that they have decent backups, but even if that's true, that's a very long and cumbersome process to restore an entire hospital system. It could be they are negotiating, and they do end up making a payment.

"Financially, they're going to be harmed and people are probably going to lose jobs over this, regardless of which way it goes."

Contact Steven Spearie: (217) 622-1788; sspearie@sj-r.com; X, twitter.com/@StevenSpearie.

This article originally appeared on State Journal-Register: Kurtis Minder, cybersecurity CEO, gives insight on hackers HSHS faces