KY’s Choctaw Academy is a marker of Native American history. Time’s running out to save it

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

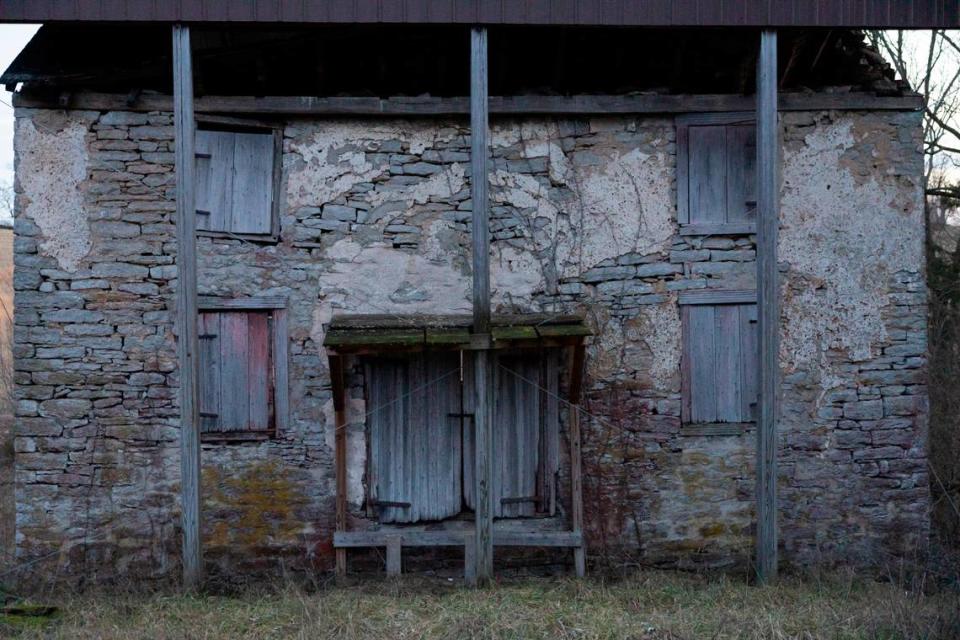

In a rural Scott County pasture, stands a monument to Native American history nearly lost to time.

The structure of stacked stone is unassuming, resembling a dilapidated country cottage. For more than a century it had been used as a barn, but in the early 1800s it was a dormitory for native boys and young men studying at a school that held the hopes of nearly a dozen tribes.

In the era of the Indian Removal Act, Choctaw Academy was created and largely funded by native tribes who wanted to break away from the proselytizing model of Christian education that came before. They hoped the school would train their sons not just in the basics of reading, writing and arithmetic, but also in advanced subjects such as geography and surveying, philosophy, history, vocal music and what we now think of as the sciences.

With the help of a largely forgotten Kentucky statesman and the nation’s ninth vice president, Richard Mentor Johnson, Choctaw Academy became the second school funded by the federal government. The first was West Point.

At least one of Choctaw Academy’s students went on to attend Transylvania University and study medicine. The school’s instruction — showcased by exhibitions during which students recited Cicero to large audiences — was so appealing white families sought permission to send their sons there.

Underlining it all was the hope for a new generation of Indigenous leaders who could stand on equal footing with educated white men and defend their communities from exploitation in the halls of American power.

Dr. William Richardson, a Georgetown ophthalmologist and a lover of history, has been trying to restore what remains of Choctaw Academy almost since he bought the farmland it stands on more than a decade ago. He posts regular updates about the project’s progress on the page Save the Choctaw Academy on Facebook.

While he’s had some success raising money, his optimism about the project waxes and wanes. Richardson still hopes he’ll find the right investor who can help him reach his fundraising goal of $290,000 and eventually open the building to the public.

“I do know that it’s not going to stand for much longer,” Richardson told the Herald-Leader in an interview late last year. It’s a fate he desperately wants to avoid.

“I can’t let it fade from memory,” Richardson said.

The Nameless Choctaw

Christina Snyder, the Penn State University historian and professor who wrote perhaps the most authoritative book exploring the Choctaw Academy, “Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers and Slaves in the Age of Jackson,” tells the evocative story of “the Nameless Choctaw” shared among the tribe’s people. In a way, Snyder writes, it became the story of the young Native men who went to study at the academy, hoping to make new names for themselves.

The tale centers on the son of a Choctaw chieftain who, though strong, brave and expected to have a bright future, is unlucky in war and fails to earn a new name for himself as a young man, as his culture demands. To his family, he is known as the Nameless Choctaw.

The Nameless Choctaw falls in love with a young woman from his village, who loves him back, but she cannot become his wife until he wins a new name in battle against the tribe’s enemies. War kindles between the tribes and the opportunity arrives for the Nameless Choctaw to finally prove himself, though word reaches his village, and his would-be wife, that he had been killed in an ambush.

Stricken by grief at the news, the woman died within the month, though, as Snyder puts it “she did not meet the Nameless Choctaw on the path of souls.”

The Nameless Choctaw survived the ambush, however, for he was not there. Tasked with spying on the enemy some distance away, the Nameless Choctaw was pursued by Osage warriors until he lost them but was in turn lost in a strange land.

Lost in the wilderness, the Nameless Choctaw called out to the Great Spirit for aid, and the Great Spirit obliged. A great, white wolf appeared and led him home. The Nameless Choctaw returned to his people, yet to them he was a stranger they didn’t recognize. When he learned of his lover’s death, he wailed a mournful song.

Under a clear night sky, the Nameless Choctaw visited her grave, collapsed on the spot and died of his grief. The white wolf howled, and it is said to howl still in the pine forest where the two lovers were laid to rest.

Peter Pitchlynn, or Hatchotucknee (“Snapping Turtle”), was a student at Choctaw Academy and heard the story of the Nameless Choctaw in his youth. The tale stuck with him into old age. In many ways, Snyder writes, it served as a cautionary tale for his own generation.

“For the first time in hundreds of years, there were no wars to fight,” Snyder writes in her book. “And yet, in many Native cultures, warfare was an essential part of masculinity…

“To avoid the sad fate of the Nameless Choctaw, Pitchlynn and his generation, with the help of their elders, had to imagine a different future, another path to manhood, a new way to earn their names,” Snyder writes in “Great Crossings.”

In this time, when conflict “moved from the battlefield to the treaty table,” as Snyder puts it, it was the hope of Choctaw elders and the leaders of other tribes that they could raise up a new generation of warriors. Ones who could do battle against a greedy American government bent on hoodwinking Indigenous people out of their lands through strong-arm negotiations. What the Choctaws and other tribes really needed at the time was good lawyers.

A school of their own

As Snyder outlines in “Great Crossings,” Choctaw Academy grew out of a desire by Choctaw leaders to make a clean break from the missionary model of education they’d experienced. That model centered on Christian evangelism and often put its students to work in the fields, rather than the classroom.

They found a partner in Richard Mentor Johnson, the Kentucky statesman and vice president to Martin Van Buren. Johnson’s initial claim to fame was that of an accomplished fighter. A veteran of the War of 1812, he was credited with killing the great Shawnee chief and warrior Tecumseh.

It was Johnson who persuaded the federal government to fund Choctaw Academy on his Blue Spring farm in Scott County. In 1825, with the Choctaws of Mississippi funding most of the project with proceeds from the lands they ceded to the U.S. government, the school opened.

Johnson’s motives are open to question. According to Snyder, he was in debt and hard-pressed financially after his family’s investments in trading and mining operations out West failed. The school, funded largely by tuition paid by the Choctaws, was an important source of income for Johnson.

“He definitely skimmed off the top the entire time, and he was even quite forthcoming about that in his private letters,” Snyder said of Johnson in a December interview.

To manage his affairs while he was away in Washington, D.C., Johnson relied on his common-law wife Julia Chinn, an enslaved mixed-race woman. Johnson fathered two daughters with Chinn, and though he insisted they be educated and treated like his own children and his family be accepted in Antebellum society, he never emancipated Chinn.

It may be Johnson’s desire to contain costs was a contributing factor in the school’s decline. In the 1830s, after the passage of the Indian Removal Act, the school’s focus shifted toward vocational education, rather than academic. According to Snyder, the U.S. government continually tried to introduce manual labor into the school’s curriculum, and eventually, trades like tailoring and blacksmithing were introduced.

In 1833, an outbreak of disease spread by a larger cholera pandemic killed 14 of the academy’s students, Snyder said. At the time, the school had an enrollment of about 150.

The U.S. government’s shifting policy toward Native Americans, combined with the changing focus of the school’s curriculum, eventually led more and more tribes to withdraw their support. In 1848, the school closed its doors for good.

Though it may seem like a failed experiment to some, Snyder sees the school’s legacy differently.

“Ultimately, what they came away with is the idea that they [Native Americans] do want to pursue schooling, but they want to do it on their own terms,” Snyder told the Herald-Leader.

That view is shared by Choctaw leaders today, according to tribal historian and archaeologist Dr. Ian Thompson. According to Thompson, Choctaw Academy represents the tribe’s efforts “not to be passive victims” but to look out for their own future.

Tribal leaders did what they could to ensure their tribe’s future was one of stability and success, Thompson told the Herald-Leader.

As for Richardson, the Georgetown doctor still trying to save what’s left of Choctaw Academy, he realizes it’s not something he can achieve all on his own.

“It’s up to the public to decide through their contributions whether or not this is something that’s worth saving,” Richardson said.

Those interested in contacting Richardson can do so through the Save the Choctaw Academy Facebook page, where they can also make a donation to the project.

Do you have a question about Kentucky history for our service journalism team? Let us know via the Know Your Kentucky form below, or email us at ask@herald-leader.com.