L.A.'s independent bookstores reckon with diversity (or the lack of it)

On June 23, author Carmen Maria Machado announced she had canceled her virtual event with Tattered Cover, Denver’s oldest independent bookstore. “Unlike the owners,” she wrote, “I know that choosing neutrality in matters of oppression only reinforces structural violence.”

The issue was that while many bookstores had supported recent Black Lives Matter protests by curating reading lists and centering Black authors, Tattered Cover had released a statement last month proclaiming neutrality on all issues of “public debate.” It later apologized after several employees quit and authors canceled virtual events.

The incident may have been an unfortunate anomaly, but it also afforded a publishing industry already facing criticism for racial disparities in its dealings with authors and editors to focus on the other end of supply chain — the stores that decide which books to put in front of readers.

Across L.A., a thriving ecosystem of independent bookstores is engaged in conversations about inclusiveness in bookselling, especially as Black and antiracist-themed titles have come to dominate Southern California’s bestseller list. “We try to keep our politics present in terms of the books we buy,” said Adam Lipman, manager of Small World Books, a white-owned bookshop on the Venice boardwalk, but he conceded that selling books by lesser-known authors is not always easy.

“There’s lists going around now of diverse books that stores should stock,” Lipman said. “But we’ve had many of those titles. And ones by some Latinx authors, or fiction which deals with inner-city lives of African Americans, just didn’t sell.” The store has since reordered some of those titles, but Lipman’s frustration is not uncommon for booksellers with small marketing budgets and “razor-thin” margins. Both of these factors disincentivize taking risks on authors who don’t have publishers investing in promoting their books.

The largest such investment comes in the form of cooperative agreements, wherein bookstores get a percentage back on purchasing volume from a major publisher — thus encouraging a focus on titles published by the large conglomerates rather than smaller presses. Both white store owners interviewed for this story had made such arrangements, while none of the owners of color had.

Whatever their relationships with publishers, it seems clear that personalized local curation has helped drive the resurgence of independent bookstores in the face of first Barnes & Noble’s expansion and then Amazon’s domination. (There are now about 1,900 independent booksellers in the U.S., up about 35% from 2009.) In contrast to Barnes & Noble, which until recently made bookselling decisions nationally, and algorithm-driven Amazon, indie stores’ relationships with customers — mostly local readers — allow them to have direct, targeted influence over what is bought and read.

Reparations Club, near West Adams, specializes in books and products by Black creators. Founder Jazzi McGilbert argues that stores don’t just respond to what’s selling; they drive it. “To the idea that books by people of color don’t sell, I would ask [the store], are you putting these books at the front? How are you engaging with people who might be interested in these books and maybe assume you don’t carry them because, traditionally, you haven’t?” Reparations Club has seen strong sales of Black magazines, poetry books, zines and self-published work by local authors — which she attributes to the way the store and website were curated long before the pandemic or the resurgence of Black Lives Matter.

Kristin Rasmussen, manager of the white-owned Pages bookstore in Manhattan Beach, agrees that staff recommendations make a big difference. “I can usually tell who’s been working that day based on what’s been sold,” she says — knowing who their favorite authors are. She adds that the bookstore promotes authors of color by facing them out front and including them in a staff-picks section.

Small World has also used its staff picks section to boost authors who aren’t “old white men,” as Lipman puts it. “I don’t know what kind of impact it has on a grand scale. Maybe authors don’t recognize they sold 20 more copies at Small World Books, but for us, it makes a huge difference.”

Small World declined to share the demographics of its staff, and Lipman said its customer base fluctuates depending on the season. Pages, which currently does not have any staff of color and caters to a predominantly white community, admits it has work to do in promoting more diverse voices.

Both stores are probably quite representative of their industry, although it’s hard to say for sure: The American Booksellers Assn. does not have data on store ownership or staffing by race. (It is conducting a survey now.) But only 129 — or 6.8% of its member stores — are Black-owned.

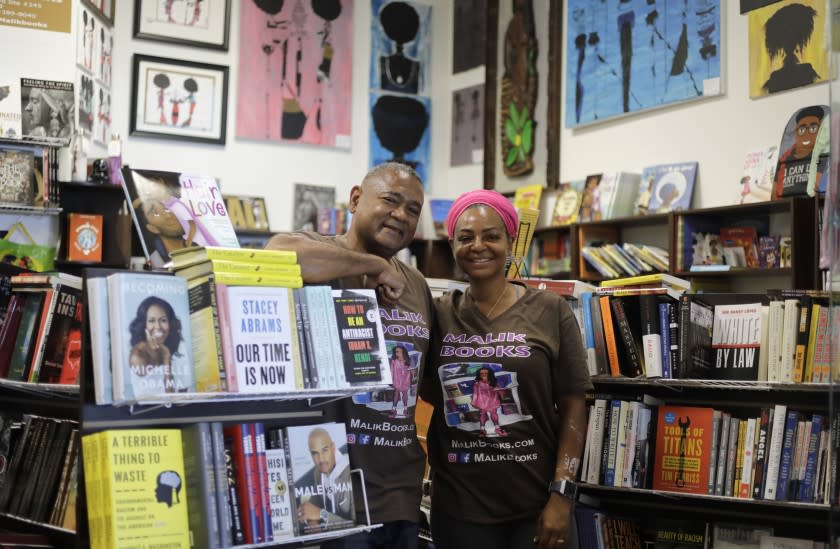

“Before the pandemic, a lot of young people came into our store looking for the same thing that Malik looked for when he was their age,” says April Muhammad, who runs Malik Books with her husband, Malik Muhammad. Since opening in 1990, the Black-owned store in Baldwin Hills has carried a wide selection of children’s literature and books on African American history. Now, after the death of George Floyd and the justice movement that followed, the store’s sales have increased tenfold, with significantly more white customers walking through Malik’s door.

Tia Chucha’s in the San Fernando Valley, which specializes in Xicano and Latinx literature, reports selling more books online today, with its physical location closed, than it did in-store before the pandemic. Rosalilia Mendoza, the manager and the store’s only employee, has struggled to keep up with demand while finding literature beyond the bestseller lists that advances the principles of Black Lives Matter. The store prides itself on featuring local and self-published authors, offering an important avenue for lesser-known writers to connect with audiences.

Of particular help to her was James Fugate, the owner of Eso Won Books, a 40-year-old independent bookstore in Leimert Park that’s been doing very brisk business lately. Fugate’s recommendations and advice have “been really helpful in expanding our list,” she says.

The sense of community among L.A.’s bookstores is strong: Pages and Eso Won are hosting a joint virtual event later this month, featuring James McBride and LeVar Burton. Last month, Skylight Books tweeted asking customers to “support black bookstores like LA’s own @EsoWon, Malik Books, and the Free Black Women’s Library.” Nationwide, the ABA has committed to centering more Black booksellers in its programming, offering trainings on antiracist allyship and taking steps to improve diversity on its board.

Despite those efforts, Black-owned bookstores bear some outsize burdens alongside the benefits of rising sales. Last month, Frugal Bookstore, Boston’s only Black-owned bookshop, issued a statement pleading for customers’ patience with delays and back orders.

“I was really glad they said something, because we’ve been feeling that burnout too,” says Reparations Club’s McGilbert. Her store has sold more books this past month than it has since opening more than a year ago. The customer base has also changed, from mostly Black and brown people in L.A. to white people across the country and beyond, with orders coming in from Canada, Australia and Japan. For the first time, publishers have also been reaching out to them in an attempt to “course correct,” as McGilbert puts it. But all this growth has come at a price. “Especially when the protests were at their peak, emotionally, it was really difficult to hold space as a Black person while trying to scale up the business,” she says. “It’s bittersweet that it took Black death, Black trauma, for us to be seen.”

It’s clear that white-owned bookshops have work to do: A list of demands for Tattered Cover compiled by the Word, a Denver nonprofit, appears to be a good place to start. The letter asks the store to set specific goals for hiring from marginalized communities, increasing diversity in titles and events, and waiving event and display fees for authors not published by conglomerates.

In the meantime, BIPOC-owned bookstores hope people continue buying books from them — and not just antiracist books. “Changing your buying habits can mean buying things made by Black people and buying from Black and POC-owned businesses,” says McGilbert. “If people truly want to vote with their dollars, it will take that commitment.”

Raksha Vasudevan's writing has appeared in the Literary Hub, Nylon and elsewhere.