What exactly is the Triforium? And other tales of L.A.'s public art

Any public art in Los Angeles must be reconciled to the fact that much of what we see in our city, we see through the windshields of our cars, as we zip past faster than any stroller, skateboarder or cyclist can.

Now it’s spring, and as COVID retreats from its trench warfare against us, we’ll be out and about. What will we see, and what should we be looking for?

Public art in L.A., and its mission, have been altered by time and perspective — not art-class perspective but cultural perspective. In the open-air gallery that is L.A., “public art” doesn’t just mean public-sanctioned art. (Murals and neon have their own place and will have their own columns here presently.)

As for this space right here, it can’t possibly be exhaustive, so don’t @ me about not mentioning your favorite. Just share this column and add your own suggestions in the comments.

“Public art” used to mean sanctioned statues of old white guys memorialized for some deed whose merit has now in some cases become debatable. The Christopher Columbus statue in L.A.’s Grand Park was spirited away a few years ago. The statue of Sen. Stephen M. White, who persuaded Congress to put up money for L.A.’s harbor, stood for nearly 90 years outside an L.A. courthouse before it was donated to San Pedro. Over those decades, Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies would prank the new guys by sending them off to the courthouse to serve a fake subpoena on “Mr. Stephen White.”

Today, our representational public statues give us figures like philanthropist/athlete Magic Johnson, at Staples Center; in Little Tokyo, “hero of the Holocaust” Chiune Sugihara, a World War II Japanese diplomat who ignored his own government’s regulations and issued visas that saved the lives of thousands of Eastern European Jews; actor and martial arts expert Bruce Lee, a statue that has become a selfie “must” for Chinatown visitors. Whenever I see it, the “Corporate Head” statue from 1990 in downtown L.A. makes me laugh: a life-sized bronze man in a business suit, briefcase in hand, his head stuck completely into the wall of a skyscraper.

The soul and spirit of our best-known industry, the movies, have always wrestled over art versus commerce, so give an eye-roll to that banner above the roaring lion on the logo of MGM, Hollywood’s premiere studio. The pious motto “ars gratia artis” is supposed to mean “art for art’s sake,” but it was cobbled together, maybe from some English-Latin dictionary, by an MGM PR man. Perfectly in keeping with the studio that filmed a happy ending to “Anna Karenina.”

Once the city outgrew literal statuary, it welcomed the memorable, the witty, the edgy. Alexander Calder’s “Four Arches,” in downtown L.A., enormous slashing steel red-orange parabolas 63 feet tall, are still bold and vivacious 45 years after they were installed.

I wonder what ever became of the commissioned statue that in 1955 was put on the facade of the LAPD’s Parker Center headquarters: a quartet of Giacometti-style elongated figures, three of them in the protective embrace of what was evidently a policeman. The artist, Bernard Rosenthal, said the figures’ facelessness was deliberate, so they couldn’t be interpreted “as belonging to any definite race or creed in preference to another." Well, this didn’t go over with some politicians or art clubs. The website publicartinla.com says one city councilman argued that “The Family Group” belonged in Communist Russia. His colleague wanted in its place a statue of Jack Webb, the dour star of the “Dragnet” TV series.

It was a half-century-plus later when new statuary went up outside a new LAPD headquarters — along Spring Street, “sixbeaststwomonkeys,” two tall, spindly simians and six low, rounded figures, a dignified procession of creatures that struck Police Chief Bill Bratton as “some kind of cow splat.” In the dozen years since they were installed, there has been an upwelling of fondness by locals for these stylized beasties.

Robert Graham’s Olympic Gateway at the Coliseum, crafted for the 1984 Olympics, was its own scandal du jour, less for what its male and female figures didn’t have — heads — than for what they did: anatomically detailed male and female bodies modeled from actual, anonymous Olympic athletes. This discomfited Graham not at all, and in 2028, Olympic visitors will see them again.

At the Bunker Hill steps in downtown stands a second Graham sculpture, “Source Figure,” a Black woman lofted high on a pillar. At the base are bronze crabs, and the most endearing explanation for them is that Cancer the crab is the astrological sign of Graham’s wife, actress Anjelica Huston, and far be it from me to ruin a perfectly charming story by trying to call Huston to check it out.

You can’t claim Angeleno-hood if you haven’t visited the La Brea Tar Pits, and if they don’t give you your fill of replica prehistoric creatures, keep driving west, and millions of years back, to the Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica, where dinosaur topiary simulacrums — half Jurassic, half-Chia pet — spurt water out their mouths (and alas, according to one property owner’s lawsuit, provide shelter for rodents).

But first, stop en route to let there be light. “Urban Light,” LACMA’s array of 202 streetlights that once illuminated L.A. streets and now stand in luminous ranks, is maybe the single selfiest place in town, save only perhaps the Hollywood sign, which began life as a real estate promotion whose gaudy flashing lights, before they fizzled out, are not to be mentioned in the same breath as “Urban Light.”

Yet here, we do not turn up our noses at kitsch, for what begins as kitsch can end as art, evidence the Watts Towers, so often close to disappearing, and now so close to the divine.

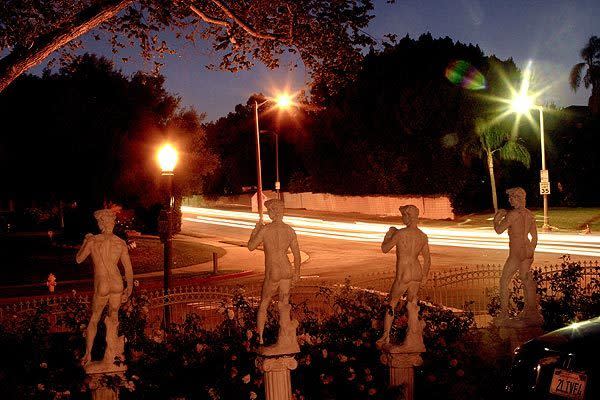

At the low end of kitsch, I truly miss — though its neighbors must not — the “House of Davids,” the Hancock Park home whose garden bristled with 19 white statues of Michelangelo’s David, like some Renaissance picket fence. They wore Santa hats for Christmas and otherwise, nothing at all.

The “art” in public art is in the eye of its beholders. For me, it’s green swags of vines hanging from a freeway overpass on Riverside Drive; the Griffith Observatory; the Frank Gehry “binoculars building” in Venice, originally an ad agency, lately rented by Google — a perfect tenant, when you think of it, given that Google can watch what we’re doing almost any time, anywhere.

Those light-and-color pylons on the approach to LAX are OK, something to take your mind off the ticking minutes as you sit mired in traffic. But put it to a vote and Angelenos would surely rather see the Space Age “theme building” restored to glamor as a restaurant and terrestrial spaceship.

And on the topic of restoration … the Triforium, oh the Triforium.

It opened in 1975 in the Civic Center to attract customers to the new underground mall below it — like the Triforium, a taxpayer-assisted project. Years ago, an online reviewer noted, accurately, “This is honestly the saddest mall I've been to.”

The Triforium has been the subject of many obituaries, all of them correct in one way or another. Tellingly, its grand debut was delayed half an hour because the sound system didn’t work. It has scarcely ever worked since then; when it did, it played everything from canticles to Janis Joplin. Brilliant in conception — coordinated music and rainbow trills from 1,494 Italian colored glass prisms — it stumbled in execution and action. The Triforium was like a car: The city owned the vehicle but the artist had the keys, and they could never quite get it together.

Before the city embarks on new Olympics-driven arts projects, it should — it should be required to — give the city its money’s worth at last, with the thrill of a consistently working Triforium.

What could it take? Rustling up about a million dollars from some foundation? Signing up a music-minded teenager who can write code to program this three-legged psychedelic nickelodeon? And look: A gift to all of DTLA and a rebuke to dull little iPods the world over — son et lumiere in the big, big Crayola box.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.