La Brea Tar Pits transports visitors to the prehistoric past

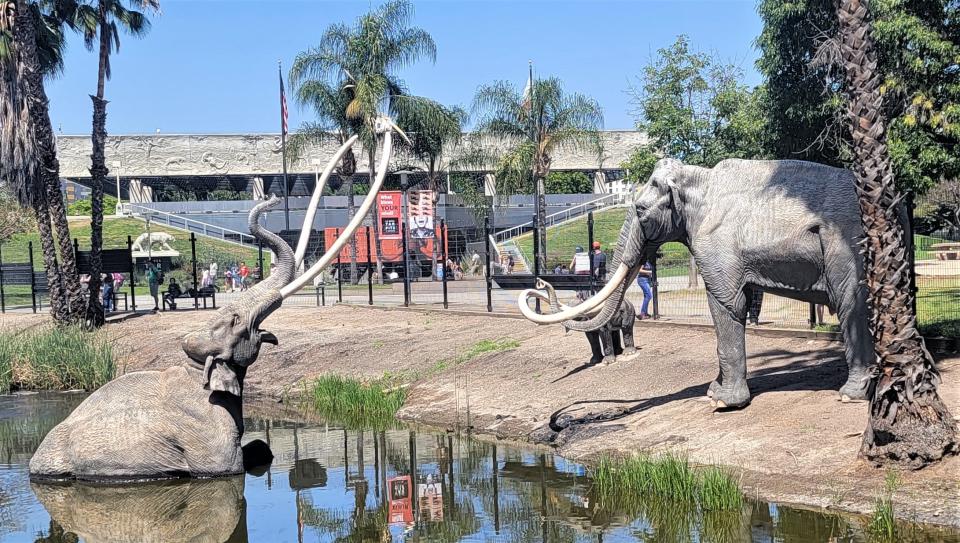

One of the most moving sights a visitor first views as they enter the grounds of La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles is the model of a mammoth family.

A large mammoth struggles to get out of the sticky black muck while its partner and child look on hopelessly.

There’s no escape possible, and the immediate future of this animal that once roamed the lands near present-day Los Angeles is dire.

Laureen and I traveled through Los Angeles and decided to stop at La Brea Tar Pits and walk around Hancock Park. We had not visited in years when our daughters were relatively young.

The same raw emotions came back in an instant when looking across the bubbling surface of Lake Pit. A family of mammoths bellowing into the heavens watching a loved one perish in a pool of unforgiving tar, is moving.

How sad that scene must have been tens of thousands of years ago. Of course, it wasn’t just the mammoths in danger when stepping into these large pools of death, but dire wolves, saber-tooth cats, ground sloths, short-faced bears, and many other animals faced the same consequences.

According to the consensus of research on this topic, when the last ice age melted in Southern California, approximately 10 to 20,000 years ago, pockets of tar bubbled to the earth's surface, creating these menacing and deadly pools. These pools were prevalent in the area that would become Hancock Park in Los Angeles.

Of course, there were other locations nearby. Still, this concentration of dark and thick lakes is where scientists have conducted over one hundred excavations since the early twentieth century.

The pools of tar are not exactly tar seeping to the land's surface but is a viscous asphalt released from deep pockets of petroleum. It is considered the lowest grade of crude oil, which sounds rather rude to me.

“You are the lowest grade of oil there is,” one oily molecule said to another. “While I, on the other hand, will someday be used to lubricate a Maserati. It is Los Angeles, after all.”

“That is a crude thing to say to me,” whimpered the lowest oil grade.

Not only were animal remains found during the multitude of excavations, which are still occurring to this day, but some early human bone fragments have been discovered as well.

While walking through Hancock Park and viewing the various pockets of sticky substances, it is easy to see how an animal or human could mistakenly get stuck in the muck.

“It just looks like a pool of water,” Laureen mentioned as we looked through the chain-link fence into one of the excavation pits.

In front of us was a large dark pool with leaves from nearby trees innocently floating atop it, but that innocent appearance could potentially be deadly for anything that ventured out onto it.

“Looks like a couple of inches deep,” I replied. “Doesn’t seem that hard to get out of it.”

But that would not be the case in most situations. Stepping into the tar pit may be the last step a living thing would take.

As an animal would walk into the muck, feet or paws would instantly sink into the thick viscous material, causing a panic reflex. The stronger the panic, the faster the animal sank and got stuck further into the muck. Soon, the struggle would slow as the animal petered out physically, and eventually, the struggle would end, and the tar would be the victor.

Remains of saber-tooth cats (not to be confused with tigers) have been found close to the bodies of ground sloths or the mammoths which perished in the pits.

According to paleontologists, those who study the history of life on earth using the various fossil records available, the predator's finding of predators and prey stuck together was a relatively simple but unfortunate play.

When a mammoth or other large creature got stuck, a predator would jump out onto the back of the beast to eat it and then find itself stuck. The predator had plenty of room outside the pool to run and leap, but once on the body of the struggling creature, it had no place to get the momentum to jump to the safety of solid earth again.

A possible scenario may have worked out in this manner.

“Dude,” said the wily old saber-tooth cat, “I’m gonna jump on that mammoth and get me a snack.”

Once on the back of the stuck mammoth, the wily old saber-tooth cat would suddenly realize he could not jump back to shore after a nibble without falling into the black muck the mammoth was stuck in.

“Hey, throw me a life preserver,” he may have yelled to another saber-tooth cat friend.

“What’s a life preserver?” may have been the response.

The pools of asphalt have been known for ages and were used by the early Native Americans living nearby as glue or caulk for their canoes. Then, settlers in the town of El Pueblo de Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los Angeles del Rio Porciuncula, or LA for short, used the material for the roofs of their homes.

The first mention of the pools in writing was by Juan Crespi, a Franciscan friar and member of the Portola Expedition in 1769, who called the pits the "springs of pitch" in his diary.

The first animal remains were found in 1875 and labeled as fossils by Professor William Denton.

A gentleman by Merriam, not the dictionary guy, but J.C. Merriam, wrote an article in 1908 calling the pools "The Death Trap of the Ages."

This article soon piqued the imaginations of pretty much anyone with interest in old dead things being stuck in muck for thousands of years.

“Let’s throw on some hip-waders and wade into the tar pits and see what’s there,” said an exuberant young paleontologist.

“You wade, and I’ll watch,” replied his wise and wary friend.

The area where the tar pits are located was once known as Rancho La Brea, which had been a Mexican Land Grant of over 4,000 acres deeded to Antonio Jose Rocha in 1828.

One curious but cool demand came with the Mexican Government land grant: all the townsfolk in the growing area were allowed to gather as much asphalt as they needed at no cost. Free asphalt for all or no land grant.

In the 1870s, the land was purchased by George Allan Hancock for the abundance of oil and asphalt located on the property. Soon though, a housing development for the ever-growing city of Los Angeles became more profitable. Still, Hancock realized something about those dark and unforgiving pools of tar located on his property warranted further investigation.

At first, many who found some bones in the muck thought them to be modern-day cattle or other animals who had mistakenly wandered into the pools and got stuck. But Hancock disagreed, and soon his family allowed research to be started on these pits of tar.

In 1909, James Z. Gilbert — a Los Angeles High School Biology teacher, began a large dig to see what there was to see in some of the oily pits.

Gilbert and his team of excavators, mainly his students from the high school, soon found fossil after fossil in the dark ponds in the area.

This teacher and his volunteer student digs were so successful that they were the force behind the development of the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art which later became the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

And who said teenagers lacked gumption didn’t know these kids.

In 1924, the Hancock family donated 23 acres to the County of Los Angeles, and Hancock Park was created. There was a stipulation: the county had to preserve and display the fossil discoveries for all to enjoy.

And as we walked around the park and La Brea Tarpits, we enjoyed the history and the beauty of the place.

Well-designed walking paths meandering here and there along grassy patches of earth intermingled with rows of tall shady trees made the meandering so much more enjoyable.

Today, visitors can witness bubbles of methane gas reaching the surface of Lake Pit and smell the rotten egg odor, which is hydrogen sulfide, for themselves.

It is fascinating.

“You know what that smell reminds me of?” I asked Laureen.

No response came from Laureen, and we continued with our walk-through of Hancock Park.

Unfortunately, we didn’t have enough time on this adventure to visit the museum itself, which has millions of plants and animal remains found during the many excavations conducted there.

Inside the museum, one can find the world’s most complete record of what life may have looked like at the end of the last ice age in Southern California.

And that should be enough for any visit.

Contact John R. Beyer at beyersbyways@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Victorville Daily Press: La Brea Tar Pits transports visitors to the prehistoric past