Hurricane season: High chances La Niña will be here for peak season. That's not good news

A budding La Niña climate pattern is expected to strengthen this hurricane season, providing fertile ground for tropical cyclones during the most volatile months in the Atlantic basin.

Scientists at the Climate Prediction Center issued a La Niña watch on Thursday, Feb. 8 in their monthly report on sea surface temperatures, giving the hurricane-amenable phenomenon a 55% chance of waking during early summer, and a 74% chance of developing August through October.

A strong El Niño, which can inhibit hurricanes with thrashing wind shear, is winding down after its June 2023 arrival. It likely will transition to a neutral phase in the spring before Pacific Ocean waters cool enough to bring on La Niña.

“It’s a pretty aggressive forecast for February,” said Colorado State University hurricane expert Phil Klotzbach about the odds of La Niña developing. “A big caveat is that it’s February. A lot can change between now and the peak of the season.”

Clash of titans: El Niño battled warm ocean temperatures during the above average 2023 hurricane season

It’s too early to say how a La Niña climate pattern may affect hurricane season, which runs June 1 through Nov. 30. But one of its features is a reduction in wind shear over the Atlantic Ocean, giving more leeway for tropical cyclones to form.

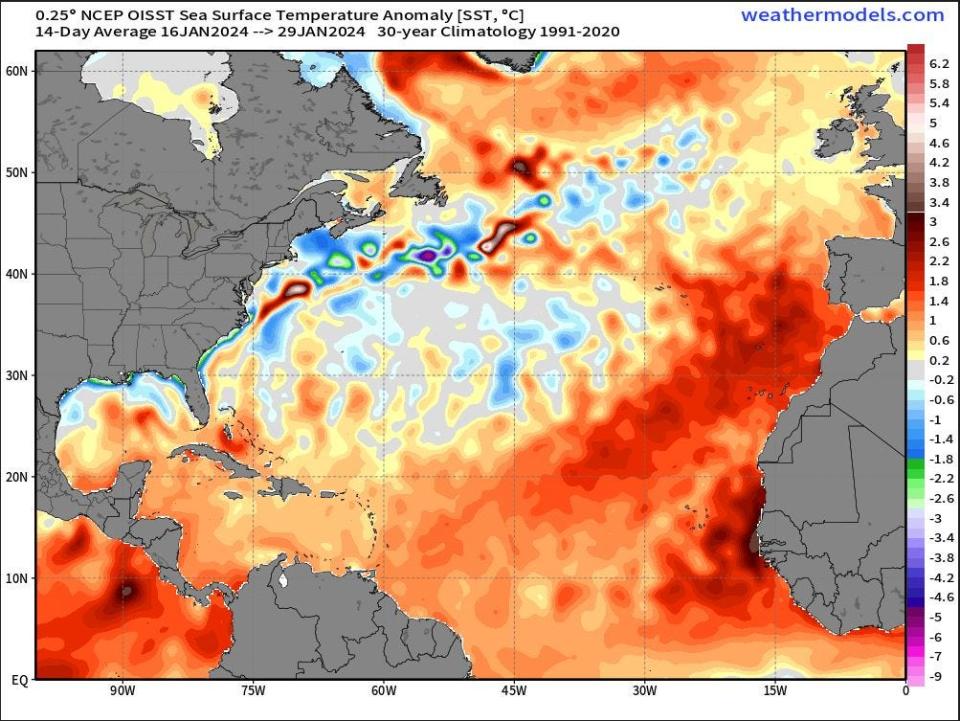

And because storms gain strength from warm water, record high temperatures in the main runway for hurricanes between Africa and the Caribbean may be a foreboding sign.

“I’m definitely not making any forecasts myself right now,” said Emily Becker, a research scientist with the University of Miami, about hurricane season. “But I think there is cause to stay alert and pay attention.”

What are El Niño and La Niña?

The climate patterns El Niño and La Niña are part of the powerful El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO.

During El Niño, warm water that has been pushed by trade winds into the western reaches of the Pacific Ocean rushes back east.

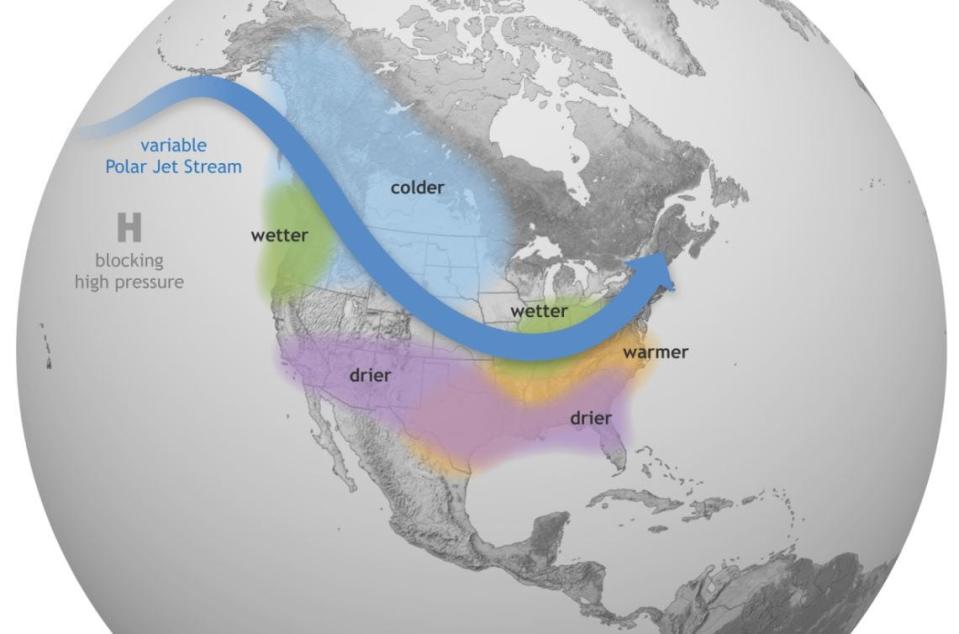

That movement shifts where deep tropical thunderstorms form. The exploding storms, whose cloud tops can touch the jet stream, disrupt upper air flows. In summer, El Niño creates wind shear that chops up Atlantic tropical cyclones. In winter, El Niño nudges the jet stream south traditionally giving Florida cooler, wetter winters.

La Niña happens when Pacific waters cool, moving the tropical thunderstorms so that the wind shear in the Atlantic wanes during hurricane season. In winter, La Niña pulses storms into the Pacific Northwest on a more northerly and inland track, holding the jet stream at higher latitudes longer where it traps cold air to its north.

But there's no guarantee that either one of the climate patterns will behave as predicted.

“This is not a weather forecast. Inherently, we are dealing with more uncertainty,” said Michelle L’Heureux, a climate scientist with the Climate Prediction Center about ENSO predictions. “There is chaos in our atmosphere but we are also mindful that there are seeds in the ocean right now that point to a transition to La Niña.”

Category 6 proposed as climate change makes hurricanes stronger

The La Niña watch comes the same week two hurricane experts released a paper suggesting the Saffir-Simpson wind scale is limited in its ability to communicate the increasing severity of storms because it caps hurricane strength at Category 5, which includes storms that reach sustained wind speeds of 157 mph or higher.

Michael Wehner, a senior scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and retired NOAA climate scientist James Kossin, looked at how a Category 6 could be used to “inform broader discussions about how to better communicate risk in a warming world,” Kossin told USA TODAY.

The proposed Category 6 hurricane would start when winds reach 192 mph or higher, speeds that have been measured in five storms over the past nine years. All of the storms that would have earned a Cat 6 title happened in the Pacific basin, including Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020 and Typhoon Surigae in 2021.

Hate it or love it, it's changing: National Hurricane Center releases new 'cone of terror' to help communicate risks

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, there is high confidence that the number of major tropical cyclones of Category 3 or higher will increase on a global scale in a warming world. At the same time, there is medium confidence that there will be fewer overall tropical cyclones or that the total number will remain the same.

Changing the Saffir-Simpson wind scale, which was developed in the 1970s, isn’t a new discussion but there has been little appetite for it at the National Hurricane Center. Instead, meteorologists have focused on raising awareness of the dangers beyond wind speeds, such as storm surge, tornadoes and flooding rainfall.

“Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale already captures ‘catastrophic damage’ from wind so it’s not clear there would be a need for another category even if the storms were to get stronger,” said NHC deputy director Jamie Rhome in an Associated Press story about the Category 6 research.

El Niño battled warm waters in 2023. Warm water won

Last year, a record-warm Atlantic Ocean and El Niño battled for dominance during hurricane season. With 20 named storms — the fourth-busiest season on record — warm water won. But just three storms made landfall in the United States, including Hurricane Idalia’s Category 3 landfall northwest of Cedar Key.

Klotzbach credits El Niño with helping steer storms out to sea by weakening the Bermuda High.

On Thursday, Feb. 8 the average sea surface temperature in the main hurricane breeding ground was 0.6 degrees Celsius (1.08 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than any other year on record. A forecast for weaker winds blowing over the Atlantic Ocean in the coming weeks means sea surface temperatures could increase into spring.

Kimberly Miller is a veteran journalist for The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA Today Network of Florida. She covers real estate and how growth affects South Florida's environment. Subscribe to The Dirt for a weekly real estate roundup. If you have news tips, please send them to kmiller@pbpost.com. Help support our local journalism, subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: La Niña: There's high chances it'll be here for 2024 hurricane season