‘La pérdida - The loss’: Deadly disaster at El Paso, Juárez border

Editor's note: The stories contain reporting and images that some readers may find disturbing.

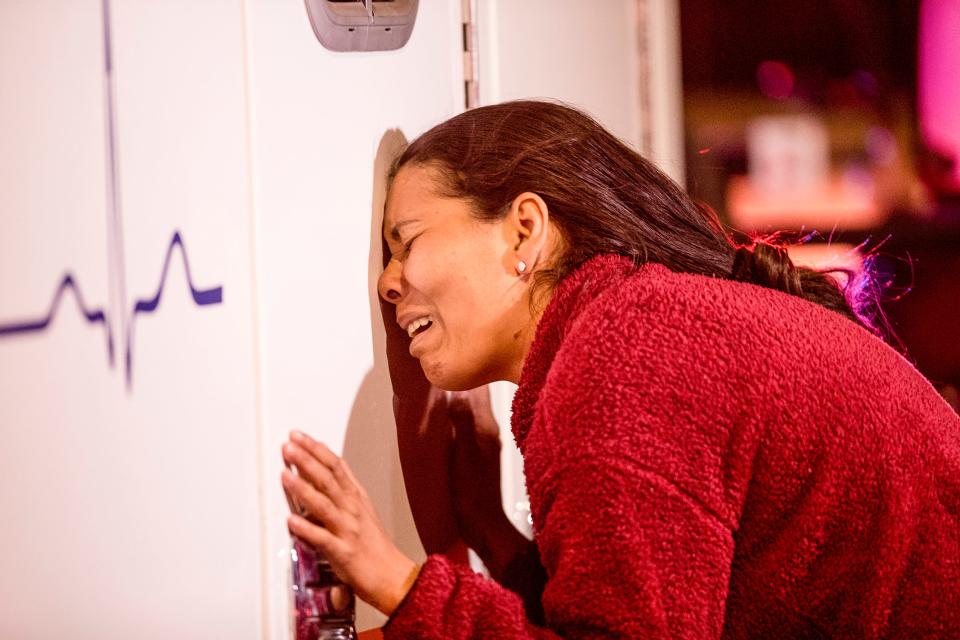

Families torn apart, dreams crushed — the somber reality of migrant deaths at the El Paso, Juárez border.

El Paso Times' yearlong investigation exposes the challenges faced by migrants and the lack of infrastructure to address this growing crisis.

Read the reports below:

Why we spent a year telling human story of deadly disaster at El Paso, Juárez border.

Jesús Iván Sepúlveda Martínez was a beloved son, husband and father of a newborn, 6-month-old Sophie.

He was just starting his own life, hoping to reach Austin to work and save money to build a house for his family.

Sepúlveda died near a waterhole when twin, 60-year-old brothers allegedly shot him while he walked with others south of Sierra Blanca, Texas, in late September 2022. Two weeks after his death, authorities returned his remains to his family in Juárez in a simple, blue casket.

“We're destroyed,” said Napoleón Sepúlveda in Spanish, weeping into a handkerchief while three family members cried on his shoulder.

Jesús Iván Sepúlveda Martínez was a migrant.

His story illustrates the human toll of the migration crisis at the U.S. border. That suffering was brutally emphasized six months later, when 40 men locked in a México detention center died when it went up in flames.

El Paso Times launched a special report, "'La pérdida - The loss’: Deadly disaster at El Paso, Juárez border."

The series, the culmination of a year of reporting, tells the human story of the sons, daughters, wives and husbands who died hoping to find a new life in the United States, and of the families and loved ones left behind.

Click here to read more about the series.

'Where is the humanity?' Migrant deaths soaring at El Paso-Juárez border with few ways to document them.

EL PASO, Texas, and JUÁREZ, Mexico — Mount Cristo Rey rises in the desert like two hands in prayer, the U.S. and Mexico sides, over a graveyard without tombs.

This year, migrants died in this harsh landscape – in the Rio Grande, in the desert, in neighborhoods and on city streets – in numbers never seen before at this border crossing known as the Paso del Norte. Yet no stones mark the places where they died, only numeric coordinates inked on police reports.

Click here to read the full report.

40 men died in the Juárez detention center fire this year. 5 came from one Guatemala community.

LA CEIBA, Guatemala — Marcos Abdon Tziquin Cuc chopped wood for his 71-year-old mother and left it neatly stacked by her cook fire before he left his rural village for the U.S. border.

The last of Juana Cuc's nine children, 20-year-old Tziquin Cuc wanted to ease his mother's burden. Later, maybe she wouldn't need kindling at all once he had a job in the United States and could buy her glass windows, wood doors and a stovetop like the homes built with U.S. dollars, peppered throughout the lush green forest of his homeland.

He never had the chance.

"The only thing I still have of him is the wood outside, because it was Marcos who brought it to me,” Cuc said. “Whenever I go for the wood, I cry.”

Click here to read the full report.

The 'resurrection' of Diego Suy Guarchaj: 'They are in the cemetery. I am alive.'

LA CEIBA, Guatemala — News of the death of Diego Suy Guarchaj came suddenly, like the autumn rains in his small village nestled in the Mayan lands of western Guatemala.

Antonio Chox, an indigenous community journalist from La Ceiba, traveled to Suy Guarchaj's nearby village of Tzucubal to report in a live Facebook feed about the young man's death.

Suy Guarchaj had lost his life in a disastrous fire at a migrant detention center on March 27, 2023, in Juárez, Mexico. Authorities released the names of the 40 deceased: Diego Suy was listed as number 12.

The citizen journalist interrupted his live feed as Francisco Suy, Diego's father, began to wail.

"Atek, Atek! (Diego, Diego!) Why did you leave me like this, Diego? I raised you, my son, Diego," Francisco Suy shouted in K'iche as he banged on the tin walls of their home.

Click here to read the full report.

'It's heartbreaking': Day after day, New Mexico investigator recovers migrant remains.

Laura Mae Williams knelt beside the body of a woman near the U.S.-Mexico border, her kneepads pressing into the searing sand.

The field investigator for New Mexico’s Office of the Medical Investigator read the ground temperature with an infrared thermometer: 125 degrees. She estimated the body – belonging to 31-year-old Yenefer Vazque, nationality unknown – had been there for three or four days.

Vazque and the bodies of 83 other “probable border crossers” were found in southern New Mexico in the nine months through Sept. 30, according to OMI data obtained by the El Paso Times, part of the USA TODAY Network.

That's up from 61 found in 2022. A surge in deaths of women accounted for most of the increase, doubling from last year and more than tripling from 2021. Seven bodies were so badly decomposed their gender couldn’t be identified.

Click here to read the full report.

Drownings in Rio Grande: They're 'ditch riders' by trade but often find migrant bodies.

Robert Rios knows the Rio Grande as few do: its vagary and speed, its awesome power to give life and take it away.

The flow of the Rio Grande has been steered by humans for a century. Rios, the water master for the El Paso County Water Improvement District No. 1, has been behind the wheel for 52 of those years.

Rios manages the “ditch riders” who monitor the water levels and control the irrigation gates on canals that crisscross farmland and neighborhoods north of the U.S.-Mexico border.

He takes water orders from farmers during the summer months. And he takes the call when the ditch riders find a body in the river. As sure as the water rises, they find the dead in the river. "Floaters," they call them.

"From the time they drown, they go down," said Rios, whose last name in Spanish means "rivers." "They don’t surface until a couple of days later, about three days after they drown. Until they float."

Most of the time, the bodies belong to migrants. People who traveled hundreds or thousands of miles across the continent, who braved jungles and raging rivers only to be deceived by a placid-looking canal the width of a backyard swimming pool. People who couldn't know that under the surface runs a current that will claw them under.

Click here to read the full report.

Dig Deeper: Drownings in Rio Grande: They're 'ditch riders' by trade but often find migrant bodies

'It is truly ugly': Family decries deadly violence migrants face in Juárez on journey to US

JUÁREZ — Her thin body was found lifeless and abandoned in a ravine in the impoverished border community of Lomas de Poleo, an area that undocumented migrants frequently traverse to cross from Juárez to Sunland Park, New Mexico.

With brown skin and dark hair, dressed in athletic clothes and blue socks but no shoes, the young woman in her 20s was lying on her back in the sand. A thick stream of blood, now dry, ran from her nose and her forehead and pooled beneath her head. Cuts on her right arm were visible through the torn sleeve of her hoodie.

“I was looking for her purse or backpack, shoes, an identification, but she had nothing with her," a state police investigator said at the scene. "This is a popular route toward the United States.”

The woman was added to a list of 69 possible migrants — 68 foreign nationals and one Mexican — who have died in Juárez between Jan. 1 and Nov. 7, 2023, according to an El Paso Times investigation. The number includes the 40 foreign migrants who died in the migrant detention center fire on March 27.

There is no exact figure on the number of disappeared and deceased migrants in Juárez.

Click here to read the full report.

In southern Mexico, the cost for migrants to reach the US is increasingly death

CIUDAD HIDALGO, Mexico — The last leg of a multinational migrant journey to the U.S. begins on a corner on Avenida Central Sur.

It's a grimy street in the heart of this city in southern Mexico on the banks of the Suchiate River. One side of the river is Guatemala. The other, Mexico. Thousands of migrants and asylum seekers stream across the murky river on makeshift rafts to reach this spot.

One afternoon in October, a municipal police officer in a navy blue uniform herded a group of migrants standing on Avenida Central Sur to a waiting combi, Mexico's most popular form of public transportation.

People crammed into the 10-passenger minivan until the combi driver could barely slide the door shut.

The stifling air inside the packed van was suffocating, made worse by the sweat of migrants unable to bathe for days in the tropical 90-degree heat.

A man clutching a backpack on his lap said he was from Haiti. He spoke in broken Spanish, which he said he picked up during a stint working in Chile after fleeing Haiti, the Creole-speaking Caribbean nation racked by extreme poverty, gang violence and political turmoil. He was headed to make a new life in Mexico City.

The others were headed to the U.S., still 1,500 miles away, through the entire country of Mexico. Some were from Venezuela, Senegal and Guinea. The lone woman, wedged in the back row, had already come all the way from Cameroon in central Africa. Scarlet-colored braids framed her perspiring face.

The combi driver shifted the transmission into gear. But at the next stop, at least five more migrants piled in, crushed together so tightly their backs jammed against the roof.

The combi was now a rolling death trap.

Migrants bound for the U.S. have long taken risks such as this. A van overloaded with passengers can turn deadly in an instant. But an unprecedented flood of migrants pouring into southern Mexico from many countries and a migration blockade by Mexico, imposed under mounting pressure from within Mexico and by the U.S., has made a deepening crisis here more deadly than ever, analysts say.

Click here to read the full report.

Efforts in Arizona to rescue migrants and identify remains are model for other states

ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT — Tom Wingo exited the charcoal-colored SUV and approached a group of about 35, mostly men and a few women, who had slipped through a hole in the 30-foot border fence separating Arizona from Sonora, Mexico.

“Welcome to America,” he told the group, eliciting smiles as they began to chat excitedly and tried to figure out who he was.

Wingo has volunteered with Human Borders for nearly eight years. He normally wears khaki pants, a red long-sleeve shirt and a cowboy hat. The red shirt matches the red sign on the side of the SUV with a white cross and the words “Samaritanos sin Fronteras,” Samaritans Without Borders.

After crossing the fence, the group sought U.S. Border Patrol agents to turn themselves in for asylum processing. But Tom knew it would take some time for them to arrive because border agents along this stretch of the border are stretched thin.

The group had traveled to the U.S.-Mexico border from India. They spoke limited English but managed to convey that some in the group had been traveling for nearly six weeks, flying to Europe before making their way to northern Mexico.

Wingo directed them to one of six new water stations that Humane Borders installed along the border fence in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Since the summer, this park has become one of the busiest areas along the entire southern U.S. border, with agents picking up hundreds of migrants every day.

“In 2 minutes they (smugglers) can cut the wall, people come through and then they take off. And then Border Patrol finds the people, finds the hole, and then calls the welders, and so it’s a constant circle,” Wingo said.

A few hundred yards away from the water station where the group of migrants from India waited, farther down along Puerto Blanco Drive, a dirt road that rings the rugged desert landscape of the national monument, U.S. Border Patrol agents set up a station over the summer.

It has yet to come down. Large brown military tents poke out from the towering saguaros that provide shade for migrants picked up by agents and waiting to be transported.

Each day on Arizona State Route 85, dozens of white vans carrying up to 15 people, and large white buses with the capacity for 50 more, take migrants from Organ Pipe to the Ajo Border Patrol Station for processing.

Click here to read the full report.

This article originally appeared on El Paso Times: El Paso Times investigation exposes challenges faced by migrants