Lab leaks and accidents up 50pc as fears grow dangerous viruses and bacteria could escape

Laboratory leaks and accidents have risen 50 per cent in Britain since Covid-19 emerged, an investigation by The Telegraph has found.

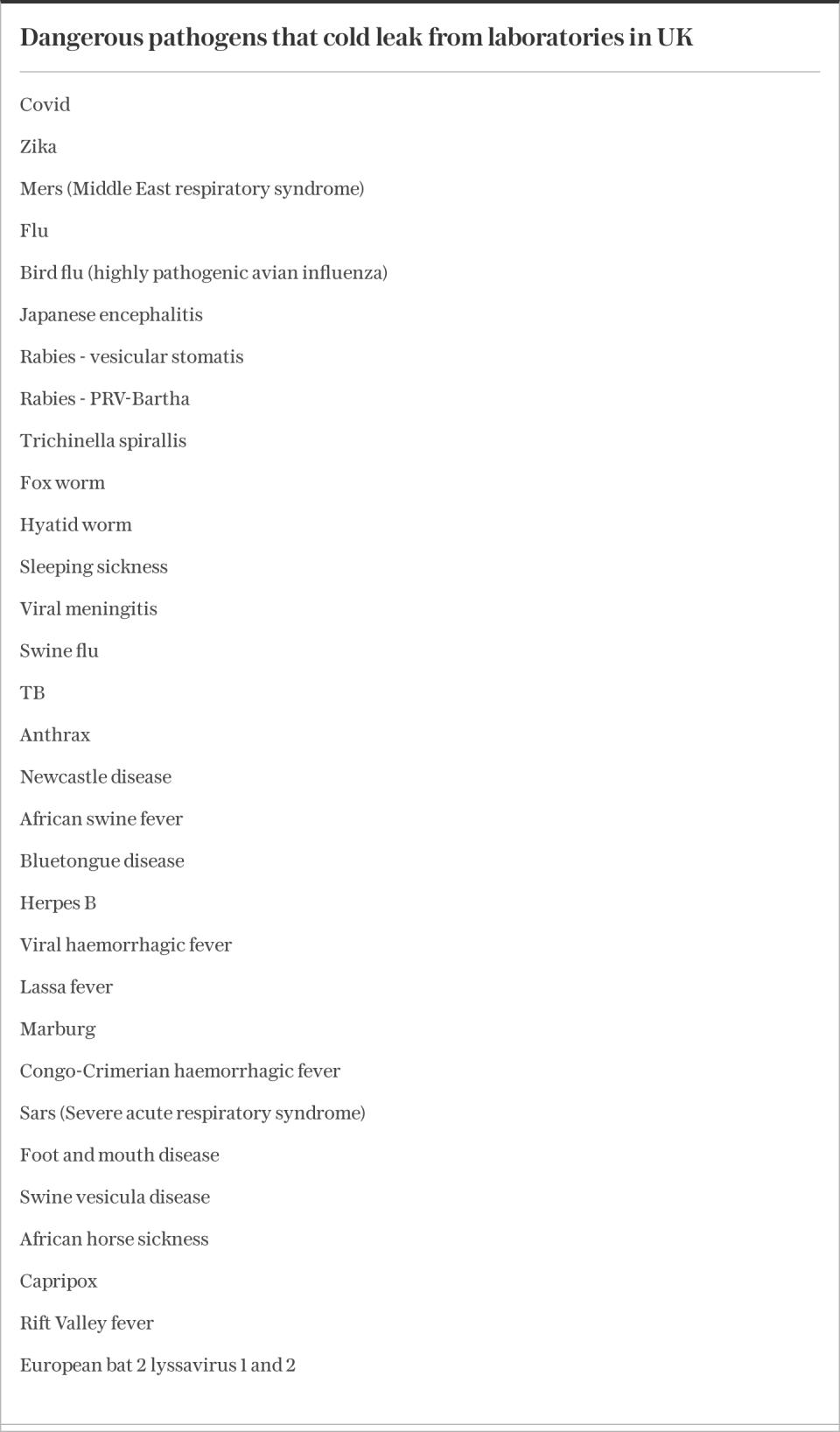

Freedom of Information requests to all British universities, government research bodies and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) showed dozens of dangerous viruses and bacteria including anthrax, rabies and Mers (Middle East respiratory syndrome) are being stored close to large populations, potentially placing citizens at risk.

Accidents at labs in the last decade include a worker at York University being pricked with a needle being used to infect mice with the parasite Leishmania donovani.

At a former Public Health England (PHE) lab at Heartlands Hospital in Birmingham, a worker was pricked with a needle containing HIV, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 2, and Candida albicans.

Emergency fumigation was carried out in the same lab after a worker dropped plates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bug responsible for TB.

Between January 2010 and December 2019, the HSE recorded 286 incidents or near misses, around 28 per year.

But since January 2020, there have been 156 reports, around 42 per year, a rise of 50 per cent.

The HSE, which had to be threatened with contempt of court by the Information Commissioner’s Office before it would release the data, said it could not disclose full details of the incidents because some of the biological agents involved are listed in the Terrorism Act.

There are growing concerns that Covid-19 leaked from a lab in Wuhan, China.

The first cases emerged just eight miles from the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) where scientists had been experimenting with Sars-like coronaviruses.

Earlier this year, a US Senate report into the origins concluded that evidence pointed to an “unintentional research-related incident”, and the US recently stripped the WIV of its funding for conducting dangerous experiments into coronaviruses before the pandemic.

Experts have called for tightened regulation of laboratories in both Britain and abroad, warning that the next pandemic could be the result of a research-related incident, either by accident or intentionally.

Col Hamish de Bretton Gordon, former commander of Nato’s Chemical, Biological and Nuclear Defence Forces, said: “The apparent lab leaks in this country alone show we are all sitting on a ticking time bomb.

“It seems highly likely that (Covid-19) was man-made, though also likely an accident at a lab, rather than deliberate.

“The next pandemic is highly likely to be man-made, given the ease and unregulation of synthetic biology, and could kill millions of people.”

Other accidents that emerged in freedom of information requests include avian flu leaking from a cracked sample tube at a Medicines Healthcare and Regulatory Agency (MHRA) lab in Hertfordshire.

A PHE lab was evacuated at the Manchester Royal Infirmary after an accident involving a rack of agar plates containing Neisseria meningitidis, the bacteria responsible for life-threatening sepsis.

At a PHE lab in Bury St Edmunds, hepatitis C leaked on to the hands of a worker while at Queen Mary University of London, a worker was stabbed by a needle containing the Vaccinia virus, similar to smallpox.

Genetically modified mouse lost

There were also breaches of Covid lab protocol at Liverpool University which included the virus leaking out of a badly sealed swab package and infected cells being left in an uncommissioned lab.

British researchers also lost a genetically modified mouse, while a lab worker accidentally injected themselves with a modified version of Trypanosoma cruzi, a microscopic parasite which causes Chagas disease.

There have also been at least 34 incidences of exposure to Brucella bacterium in labs including University College London Hospital, the Royal London Hospital and Leicester Royal Infirmary in the last 15 years.

The Global Biolabs Report 2023 shows that the UK scores well on biosafety oversight. However, a report from Chatham House in December warned that despite stricter controls, laboratory accidents still occur regularly.

The Chatham House report identified laboratory-acquired infections in 309 individuals from 51 pathogens globally between 2000 and 2021, including 16 incidents of pathogen escape from biocontainment facilities, most occurring in research and university laboratories.

‘Potentially catastrophic consequences’

Responding to The Telegraph’s figures, Dr David Harper, the report co-author and the former chief scientist and director general for health improvement and protection in the UK Department of Health, said: “Accidental breaches in laboratory biocontainment can have potentially catastrophic consequences.

“The accidents that are reported today without doubt provide an underestimate of the true scale of the problem.

“Greater transparency, with better reporting, documentation and analysis, is urgently required together with improved governance and oversight.

“There is a pressing need for a conversation on whether a global reporting norm should be developed and what verification or enforcement processes might be necessary.”

In the last year, across Britain, including outside of labs, the HSE recorded 376 incidents of release or escape of biological agents, and 634 accidental release or escape of substances liable to cause harm.

Dr Filippa Lentzos, the co-director of the Centre for Science and Security Studies at King’s College London, said: “While lab leaks and accidents may well have risen, some of this might be the result of increased reporting of incidents.

“In terms of risks, what is more relevant than simply the number of incidents is how many of them actually resulted in infection and/or illness. I suspect not many, and certainly not much spread beyond the particular lab worker involved in the incident.

“The global post-Covid building boom in high containment labs is not being matched by accompanying risk management policies.”

The next pandemic could come from a lab

By Col Hamish de Bretton-Gordon

The next pandemic is highly likely to be man-made, given the ease and unregulation of synthetic biology and could kill millions of people.

But the only concern of the Covid Inquiry appears to be to pass the buck, and is overall a complete waste of money and time.

There has been no thought on how the pandemic started and how to prevent the next one, which, given all the bad actors out there now, and those who would do us harm, is a bit of a worry.

The worst backstabbing is on display at the Covid Inquiry but we must work out how to prevent the next one rather than just apportion blame for the last.

Many mistakes were made by politicians who did not understand the science and did not have the breadth of experience or intellect to appraise the advice given and act rationally on it.

I had a similar experience over several years trying to explain to politicians that the use of chemical gas weapons in Syria was a crime against humanity and must be stopped.

They could understand bombs and bullets, but for most “bugs and smells” were beyond them, and hence President Assad of Syria continued to murder his own people with gas.

Assad is still in power 10 years later and was even invited to Cop28.

If we continue with the same ambivalence to preventing the next pandemic, we could have a manifestly greater disaster.

Nearly four years down the line from the pandemic, we do not know how it started. It seems highly likely it was man-made, though also likely an accident at a lab, rather than deliberate.

As a biological counter-terrorist expert, the process to ensure this is less likely in future is obvious and achievable, so it is an unfathomable frustration that it is now happening.

The apparent lab leaks in this country alone show we are all sitting on a ticking time bomb!

Firstly, we need to regulate and police laboratories like Wuhan, which currently do what they like, with no external scrutiny.

There are around 4,000 laboratories and one million scientists who have the ability to manipulate the genome to create a devastating pathogen and at the moment nobody is looking too closely at them.

If the UN’s Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention was properly funded and supported, this is exactly what it should be doing.

Secondly, we now have the technology, developed in the north east of England to track, in near real time, pathogens moving around this country and the globe.

This would give actionable intelligence, apparently so lacking according to the inquiry, in order that they could make effective decisions to contain any future outbreak.

Quite frankly, if we do not prepare better for the next pandemic, all the “energy” expended to solve climate change, illegal immigration and the cost of living crisis could be horrifically irrelevant

As in the brilliant novel I Am Pilgrim by Terry Hayes, one bad actor could synthetically engineer a highly toxic and transmissible pathogen which could kill millions.

The fiction of this book from 10 years ago is the reality of today.

Col Hamish de Bretton-Gordon is a veteran British Army officer and former commanding officer of the UK’s Joint Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Regiment and Nato’s Rapid Reaction CBRN Battalion