He was ‘labeled an alcoholic at 15.’ Now he’s weeks away from graduating high school

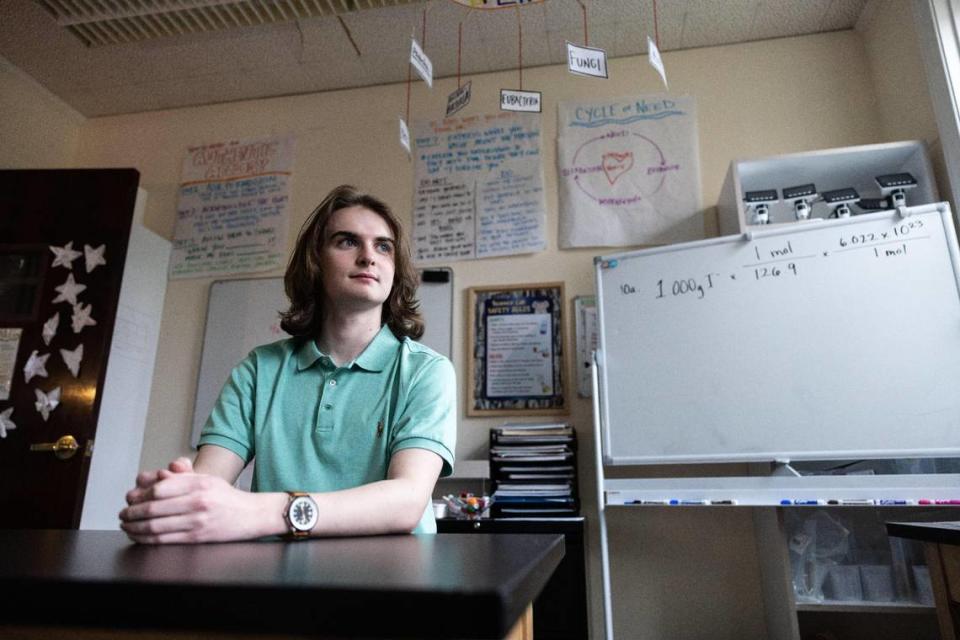

Tommy Norris is hardly a kid in crisis.

His is a story of redemption and the haven he found tucked inside a Charlotte church.

Tommy says he went from abusing alcohol, marijuana, mushrooms and LSD to now, two and a half years later, choosing which college he wants to attend: the University of North Carolina-Charlotte, Winthrop University, the University of Michigan or Michigan State.

“Even though I wasn’t doing the hardest of drugs, the drugs that people die from the fastest, I knew it would’ve gotten to that point,” said Tommy, an 18-year-old senior on track to graduate high school June 9. “And it started to get to that point.”

Instead, Tommy ended up at Emerald School of Excellence, a private, nonprofit high school designed for teens in recovery. The school sits within a Methodist church on Central Avenue and is a sanctuary for 30 teens recovering from substance abuse, co-occurring disorders, depression, eating disorders or other issues.

More than half of Emerald School’s students will graduate in June, and students like Tommy want to see it grow because he says, there are other kids out there who need help.

“I walked in, after being labeled an alcoholic at 15, and was like ‘Wow’, these kids are the same age as me,” Tommy said. “They’re having fun, but they’re sober and now it’s in a school environment.”

‘Desperation in his voice’

Tommy was 11 when he had his first drink. He was 12 when he started smoking marijuana. Both, he says, helped him fit in a friend group. By the time he started attending Fort Mill High School, he was abusing both.

“When he first started, we saw some behavior changes,” mom Bridget Norris told The Charlotte Observer. “He was acting out. We were getting calls from school. We busted him a couple of times using alcohol and weed. But we thought it was just a phase.”

Tommy was 15 when he hit rock bottom. He was home and consuming mushrooms when he had what he calls “an episode.” He threw a TV, was chewing on his knuckles and, when his dad came into his room to see what was going on, Tommy says he didn’t recognize him. He got scared and hit his dad.

The paramedics were called and Tommy was taken to the hospital. Driving home the next morning, his dad told him: “You know, you can’t do this anymore.”

“That was the first time I agreed,” Tommy said.

His mom still gets emotional about it.

“You’re finally realizing that this is out of control,” she said. “To hear the desperation in his voice. And him wanting the help and asking for it and him being really scared.”

A couple days later, Tommy was in a treatment center. He attended school at the same time.

“I was living two different lives,” Tommy said. “I’m going to a treatment place and have all of these sober friends. And then I’d go to public high school and be reminded of my past life. Willpower can only get you so far. But when it’s constantly pressed on you every day in an environment like school and you’re stressed out, it’s not going to last.”

Bridget Norris had dreams for Tommy. He was, after all, a top student. Then, the family’s priorities changed.

“We knew that we needed to keep him alive,” she said. “We knew that we had to get him sober first. Academics came second.”

Emerald School’s mission

Mary Ferreri, a veteran educator, opened the Emerald School in 2019 because she wanted to help students in recovery throughout the Carolinas. Her school was the first to open in the state and is the only one of its kind in Mecklenburg County.

The school serves grades 9-12 and receives funding from grants, private donations, fundraisers and student tuition, which is $1,500 a month year round. Ferreri says they try to provide partial or full scholarships to families who qualify and “have not had to turn any family away due to financial need.”

Ferreri, who battled the eating disorder anorexia in high school, says she wouldn’t have made it at a regular public high school if she didn’t have a modified senior year — with half of her classes in a traditional public school and half with a teacher in a one-on-one setting.

Emerald School takes the basics of a school day and tailors them to fit each student.

“The only way you can really do that is sit and talk with them and be with them,” Ferreri said. “We start the day with a meeting where they can be honest, share something that’s hard, and get support right away.”

Emerald School has four teachers for core classes, two administrators, two full-time recovery staff members and one part-time, recovering staff member. The school contracts with people who teach electives such as guitar, yoga and others.

Tommy has all the credits he needs to graduate with a normal public high school diploma. He also gets drug tested and, if at any point he needs to step out of academics and focus more on his recovery, that time is available.

Ferreri says the main goal of her school is to hold the students accountable and to teach them that there’s nothing more powerful than peer support.

“I didn’t get sober to just be lazy and take up space,” Tommy said. “I have to be a good, functioning member of society. It’s my job to pay back the unconditional support that has been given to me.”

VOTE NOW: Who's your superhero in K-12 education?

Three years sober

Tommy, nearly three years sober, is still trying to figure out what he wants to major in after high school. He’s mulling working with people who are recovering, particularly psychology and therapy.

Tommy mentors many of his classmates. He’s also trying to talk with his sister, who is 11.

“She’s the same age I was when I started,” Tommy said. “It’s important to educate her. She knows what I do, where I go to school. She knows all about it. Recovery is everywhere. It follows you.”

Ferreri says it’s important to know that Emerald School is not its students’ only support.

“We expect them to attend meetings and have outside support,” Ferreri said. “When (kids) can share a little bit about their journey, that’s when people are moved.”