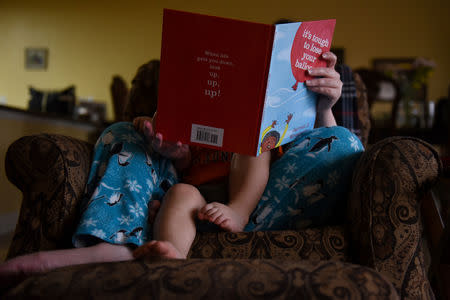

What lack of paid family leave means for one Texas mother

By Callaghan O'Hare and Maria Caspani

SAN ANTONIO, Texas (Reuters) - Her baby boy Micah is just a few weeks old and already Lauren Hoffmann is back at work. She and her husband Will had decided she would take two months off to welcome Micah, their second child, born in December 2018.

But they were coming up short.

Hoffmann, 29, only had five and a half weeks of accrued paid time off from her job as a college program manager in San Antonio, Texas.

The young couple carefully evaluated their financial situation and decided to add the remaining two and a half weeks by dipping into their savings and leaning on other types of paid leave offered by Hoffmann's employer.

"We have enough saved and I did apply for short-term disability which covers some partial payment of my income," Hoffmann said. "It wouldn't have been realistic ... to really take any more unpaid time off."

The United States is the only industrialized nation that does not federally mandate paid family leave, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and many families are faced with difficult choices like the Hoffmanns', which can result in huge financial and emotional strain.

The average paid maternity leave across the 36-country OECD bloc is 18 weeks, with some European nations granting over six months, according to the organization's data https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF2_1_Parental_leave_systems.pdf from 2016.

Most families in the United States rely on the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, which protects employment for up to 12 weeks for new mothers, but does not mandate remuneration during that period nor covers everyone.

Some U.S. private sector employers provide paid leave voluntarily and some states have passed paid family leave legislation, but not Texas.

Time is spread thin for Hoffmann.

She nurses her newborn before and after work, and pumps breast milk multiple times a day, including during breaks in a conference room at her office. After work, she usually heads home just in time for a family meal, to take care of domestic chores and pack lunch for the next day before putting Micah and two-year old Asa to bed.

"I got home last night and all I wanted to do ... was sit there and hold my baby," she said.

Hoffmann shares parental duties with her husband, an intensive care nurse at a local hospital, and she said they both struggled with the lack of sleep a newborn brings as well as the mental and financial burden that came with not having guaranteed paid leave.

"You're worried about this tiny little new life, you love it so fiercely," she said. "Having more time to feel like you're getting good at this ... I think that could only be a good thing."

President Donald Trump included a proposal in his 2019 budget plan that seeks to provide six weeks of paid leave through the Unemployment Insurance system to new mothers and fathers, including adoptive parents.

As the race for the 2020 presidential election kicks off, some Democratic candidates are also promising to pursue paid family leave policies.

In February, Kirsten Gillibrand, a New York senator who recently announced her presidential candidacy, proposed legislation that would give Americans up to 12 weeks of paid leave at 66 percent of their monthly salary. Nearly all 2020 candidates on the Democratic roster are co-sponsoring the bill.

But legislation on paid family leave has previously been introduced in the U.S. Congress, with no success.

For Hoffmann, it is a "no brainer."

"I truly do wish that the U.S., or even the state, took it upon themselves to understand the value of parenthood," Hoffmann said. "Providing time for fathers as spouses, partners as well, and to know that that time would be paid and supported is a huge burden off of a new family."

Photo essay: https://reut.rs/2tITlQc

(Photography by Callaghan O'Hare in San Antonio, Reporting by Maria Caspani in New York, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien)