Lake Michigan Triangle: The might of the Great Lakes is more powerful than any myth

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — Plenty of stories have been told about the mythical, mysterious Bermuda Triangle: a dark, dangerous stretch of water that has spawned far more questions than answers and claimed countless lives.

Did you know that some claim Lake Michigan has one of its own?

Well, not a spooky, bewildering death trap, but a mythical lore that combines history and mystery.

It is called the Lake Michigan Triangle. And while some people may believe in the myth, at least one local historian is ready to put it to rest.

ESTABLISHING MYTHOLOGY

Like the Bermuda Triangle, the Lake Michigan Triangle is a wide swath of the water comprised of imaginary lines connecting three key points — in this case commonly linked to Ludington, Benton Harbor and Manitowoc, Wisconsin.

The exact origin of the Lake Michigan Triangle isn’t clear, but the concept was first made popular by author Jay Gourley and his 1977 book “The Great Lakes Triangle.”

The book tells the stories of different shipwrecks, plane crashes and disappearances along the lake, claiming that “the Great Lakes account for more unexplained disappearances per unit area than the Bermuda Triangle.” Gourley also threw out several theories for bizarre phenomena that play a role in the triangle’s “mysterious ways” — some bound by science and some not.

For example, magnetic declination can mess with compasses and other charting equipment, so it may have contributed to some of the lost vessels. But others, like ley lines, negative energy vortexes and UFOs, fall firmly in the paranormal category.

Some of the most notable shipwrecks include the Thomas Hume, a schooner that disappeared in 1891, and the Rosabelle, a ship found flipped upside down and floating on the water in 1921.

One of Lake Michigan’s biggest mysteries — which just so happens to have happened in the designated triangle — is NWA Flight 2501.

NWA FLIGHT 2501

At the time, Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 2501 was the deadliest commercial airliner crash in U.S. history. All 58 people on board (55 passengers and three crewmembers) were lost in the crash.

The fated flight took off from LaGuardia Airport in New York City bound for a stopover in Minneapolis on June 23, 1950.

While there are several key pieces of data that detail the pilot’s issues with severe weather, the cause of the crash remains a mystery along with the location of majority of the wreckage.

Maritime historian Valerie van Heest is at the forefront of the search for the remains of Flight 2501. The shipwreck diver has helped spearhead the search with the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association since 2004, part of a joint venture project with acclaimed author and fellow shipwreck hunter Clive Cussler.

In her book, “Fatal Crossing: The Mysterious Disappearance of NWA Flight 2501 and the Quest for Answers,” van Heest breaks down what we know and what we don’t.

The plane, a DC-4, was piloted by Captain Robert Lind and his co-pilot Verne F. Wolfe. The flight plan was arranged to avoid unfavorable conditions, but forecasts fell short on just how big of a storm was brewing in the Midwest.

The Sweet House: An inside look at a piece of Grand Rapids history

The flight took off at 8:35 p.m. ET. It didn’t take long for things to turn choppy. Heading toward the storm at the flight plan’s set cruising altitude of 6,000 feet, Lind requested a drop to 4,000 feet because of the inclement weather. At first, he was denied because there was other flight traffic in the area. But by the time the plane reached Cleveland at 10:49 p.m., he was given the OK.

About 40 minutes later, air traffic control came with the request, instructing Lind to drop down to 3,500 feet. There was an eastbound flight approaching the area at about 5,000 feet. Typically, 1,000 feet in separation is considered safe, but with the eastbound flight experiencing severe turbulence over Lake Michigan, air traffic control wanted a bigger cushion.

At 11:51 p.m. ET, while flying over Battle Creek, Lind radioed in again, estimating they would be to Milwaukee in about 45 minutes. A few minutes later, as they approached the lakeshore above Glenn Township, about 10 miles north of South Haven, Lind made his last transmission, requesting a drop to 2,500 feet.

He never said why and he was never heard from again.

In “Fatal Crossing,” van Heest broke down Lind’s apparent decision to turn south after getting a firsthand look at the storm.

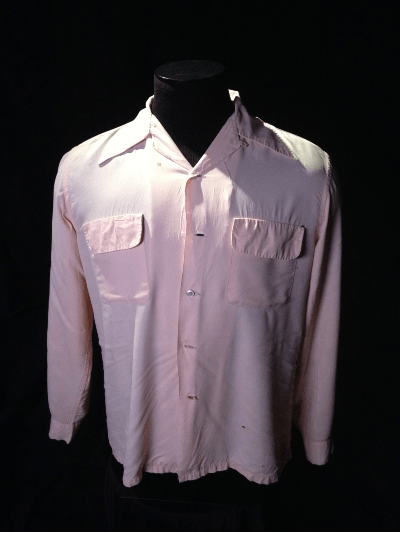

A barber kit that belonged to Merle Barton was one of several pieces of debris recovered following the crash of Flight 2501. It is now on display at the Heritage Museum & Cultural Center in St. Joseph. (Courtesy Valerie van Heest) A mannequin displays a men’s dress shirt recovered from one of the victims aboard Flight 2501. It is now on display at the Heritage Museum & Cultural Center in St. Joseph. (Courtesy Valerie van Heest) A suit jacket that belonged to Merle Barton was one of several pieces of debris recovered following the crash of Flight 2501. It is now on display at the Heritage Museum & Cultural Center in St. Joseph. (Courtesy Valerie van Heest)

“Lind could have retreated from the storm and flown to another airport to land and wait for the squall to pass. Although he knew that he had the right to do whatever he felt was necessary for the safety of the airplane and his passengers, he also knew that Northwest, like all the other airlines, preferred its pilots to avoid the significant extra costs involved in intermediate stops for any reason,” she wrote. “He could see that turning north would be no better than going forward, since lightning flashed in that direction, as well. Instead, he made the decision to turn south in an attempt, like a quarterback, to make an end run around the defensive lineup of the storm as pilots often did in that region when encountering storms.”

She also detailed several firsthand accounts of people around Glenn and South Haven who noticed the plane flying surprisingly low with the storm hot on its tail.

It took less than an hour for flight officials to realize something was wrong. Flight 2501 was radio silent and the pilots never contacted their next checkpoint in Milwaukee. By 1 a.m. ET, 80 minutes before Flight 2501 was due in Minneapolis, Northwest Airlines called Michigan State Police and notified them of a possible crash. They couldn’t confirm anything for several more hours, not until dawn and not until the DC-4 would be completely out of fuel. But in their stomachs, they knew.

Sign up for the News 8 daily newsletter

The following evening, after receiving a tip from a local fishing boat, a U.S. Coast Guard crew found some debris and an oil slick about 12 miles off the shore near South Haven.

The gory scene is detailed in van Heest’s book, but the giant banner headline atop that day’s issue of the Grand Rapids Press said all that needed to be said: “DC4 falls in Big Lake: 58 lost.”

LOOKING FOR ANSWERS

What happened to Flight 2501? We don’t know exactly, and we likely never will.

Why haven’t we found what’s left of Flight 2501? Van Heest explains it matter-of-factly, framing the context around the facts to help understand why so many answers can be hard to come by. Searchers haven’t found Flight 2501 because it’s no longer a plane. Not anymore.

1883: The logjam that nearly sank Furniture City

“The difficulty of finding that is it is an airplane that flew at 180 miles an hour and from the debris that was recovered from the lake, we knew it broke up into indistinguishable parts,” van Heest told News 8. “That makes the target on the bottom very difficult to find. In southern Lake Michigan, the bottom topography is very mucky and silty. It is quite possible that the remains of this plane have sunk into the muck and may never be found.”

Did magnetic declination mess with the pilots’ instruments? What about that mysterious pattern of stones deep underwater near Grand Traverse Bay? Can we rule out aliens?

Or is it Occam’s razor? The simplest solution is likely right. Like any trip thousands of feet off the ground, it’s always a gamble and sometimes they come up snake eyes.

Just like any discussion about the Lake Michigan Triangle, van Heest is firmly on Occam’s side. And the historian doesn’t mince words when it comes to talking about facts.

“The Lake Michigan Triangle is the fabrication of a creative writer who is trying to generate hype for all the mysteries of ships and planes (that have) gone missing in the Great Lakes,” she said. “The Great Lakes are dangerous bodies of water. The shores are closely spaced. We get tremendous storms. In years gone by, there are literally thousands of ships sailing the Great Lakes and when you have traffic and storms, you have tragedies.”

Long live the king: James Jesse Strang and Michigan’s last brush with ‘royalty’

She continued: “I have done an in-depth accounting of shipwrecks on the Great Lakes and the predominance of their locations are off the big cities of Chicago and Milwaukee and also along the shore because lower Lake Michigan has virtually no natural barriers where ships can take refuge in big storms.”

And finally, to put the debate to bed, van Heest contradicted Gourley’s previous claims, saying “There are actually fewer shipwrecks in this purported triangle than elsewhere on Lake Michigan.”

Myth and mystery are one thing, but more often than not, science and hard data tell the real story.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WOODTV.com.