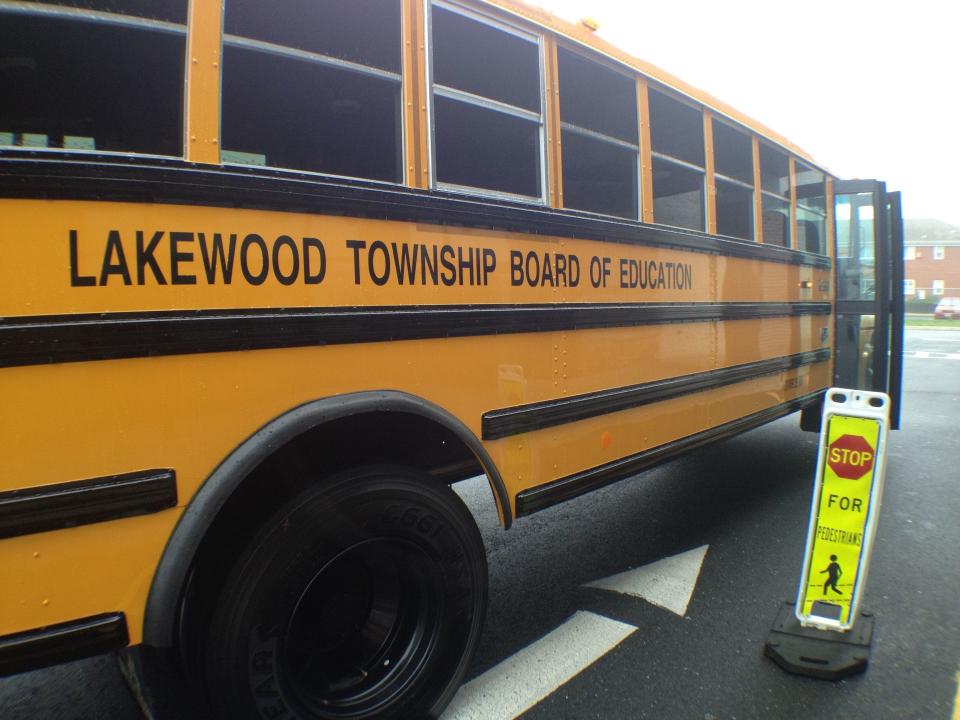

Lakewood schools borrowed millions from New Jersey and still can't pay its bills

LAKEWOOD – Would you keep loaning millions of dollars if there was little chance of it being paid back?

If you’re the state of New Jersey, you apparently would.

In this case, the borrower is the Lakewood School District, which says it is so broke it needs to borrow $93 million from the state this year to keep its doors open.

That $93 million would be on top of the $165 million the district has borrowed since 2014. It has only managed to pay back $42 million. That would bring the district’s state debt to more than $198 million, an amount unlikely to be repaid anytime soon.

The courts and even the state auditor agree that the main reason the district is in "severe financial distress" is because it doesn’t get enough aid from the state.

MORE: Lakewood Schools borrow more money from New Jersey than any other district

So far, Trenton has resisted calls to fix the problem. Even though an appeals court ordered the state to change the funding formula for Lakewood six months ago, the state Department of Education is just now launching a review, which will take at least another six months.

It’s almost as if the state’s school funding formula has set up the Lakewood School District to fail.

“The primary problem in Lakewood is the existing funding formula,” said David Sciarra, former executive director of the New Jersey Education Law Center. “In its current format, it can’t provide Lakewood the funding it needs to deal with its unique circumstances.”

Here’s why the funding formula doesn’t work:

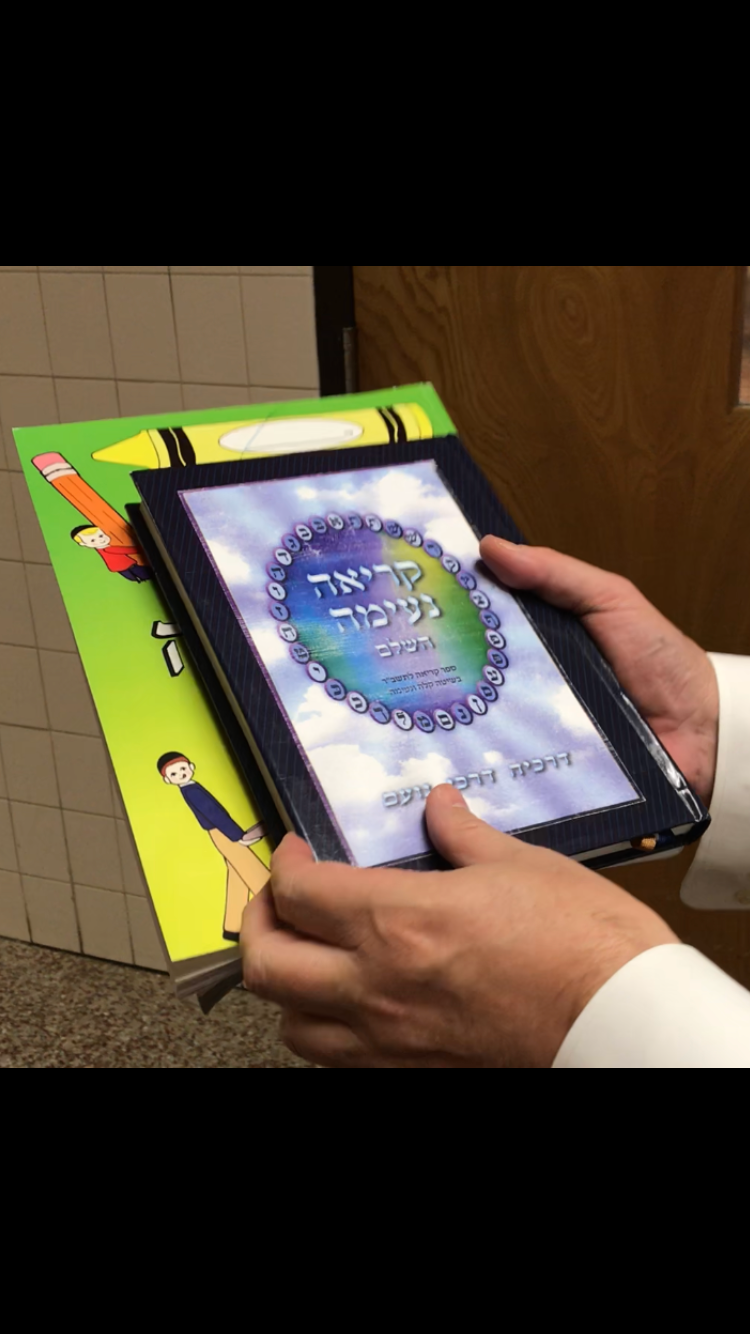

Lakewood currently has eight times as many students in private school, 42,307, as public school, 5,164. The state mandates that districts pay for transportation, special education textbooks and certain other expenses for private school students, but Trenton doesn’t fully reimburse for those costs.

Lakewood receives $710 per student to cover busing. But that can be as much as $455 per student less than it actually costs to bus students to one of its 181 private schools, meaning the district starts the school year already behind.

About a quarter of the state's private school students — and 95% of Ocean County's — live in Lakewood.

The state reimburses Lakewood for the tuition costs of its special education students based on a statewide formula that assumes 15.9% of students need special education; Lakewood’s average, however, is 33.4%, and the district has to make up the difference, according to the state auditor.

Lakewood’s money woes are well known to the state, and have been allowed to continue for years. In order to keep school doors open, the state has allowed Lakewood to keep borrowing money - totaling more than $165 million - since 2014 in ever-increasing amounts. The district still owes $123 million, yet there has been no action plan on how to pay all the money back.

Even though Lakewood says it can’t pay its bills without a loan, it does not always operate as a poor entity. Just last month, the district approved a $22,000 raise for its superintendent and its board attorney earns more than $800,000 per year, among the highest in the state.

NJ Auditor: Lakewood schools deserve special 'state aid' to address finances

Students and parents say the quality of public school education suffers. They complain about teaching vacancies being frequent and having students learning through online courses and substitute teachers, or merging different groups of students that were on different study tracks.

“It’s really disappointing that our opportunities are being taken away just so that other kids could have the privilege to go to a private school,” said Maria Torres, a Lakewood High School senior.

“We could be getting better books for school, or they could renew stuff in the schools, but how could they do that, if the district doesn’t have enough money, because the adults that are managing our money are giving it out to private schools as if they needed it more than the low income students that go to public schools,” Torres said.

“You have to be in a position to pay your bills,” said Richard Bozza, New Jersey Association of School Administrators executive director and former superintendent in Montville and Berkeley Heights. “If you find that your resources don’t allow you to do that, you have a significant problem.”

Anatomy of a crisis

State education officials agree that Lakewood is unique. It is one of the fastest-growing municipalities in the state -- its population has more than doubled since 2000 to nearly 140,000 people. Its public schools annually face a financial crisis in part because of crushing costs to bus many Orthodox Jewish students to private schools on separate buses for boys and girls.

New Jersey decides how much money it sends each school district by a complicated formula based on how many public school students are enrolled and the wealth of the district.

What sets Lakewood apart is the makeup of its student enrollment. The district has 5,164 public students and 42,307 private school students.

The Lakewood School District spends $138 million on private school students, while its student-based budget for public school students is only $39 million.

A state auditor's report shows that only 18% of all tuition and transportation expenses between 2014 and 2021 were for public school students.

“From fiscal years 2014 through 2022, Lakewood school district’s nonpublic enrollment rose from 23,652 to 42,396, an overall increase of 18,781 students (79 percent),” Kaschak wrote. “During that same period, the number of nonpublic schools increased from 88 to 164.”

This year, the number of nonpublic schools in Lakewood increased again, up 17 to 181.

MORE: NJ wants financial review of Lakewood Schools after court orders more funding

As presented in the 2023-24 district’s budget, Lakewood is set to spend $138 million on private school-related expenses. Those include $27 million for private school transportation; $55 million on resources for private schools such as security and technologies; and $53 million in private special education tuition. These expenses are state-mandated.

The district’s entire state aid is about $46 million, for both private and public school needs, according to the district.

So how can the district meet these demands? Simply put, it doesn’t.As it stands now, the only way the district can afford to pay for these state-mandated costs under the existing state funding formula is to keep borrowing money.

And borrow it does: If it gets the $93 million loan this year, the district will owe the state $198 million. The district intends to pay back $17.5 million this year, but only by taking it from the school aid it receives and giving it back to the state as a loan payment.

What’s worse is neither the district nor the state has a plan that would realistically allow Lakewood to pay back its loans and get out of debt. The state says its state aid number to Lakewood includes mandatory debt repayment. But with Lakewood taking out bigger and bigger loans since 2014, that means it has more and more to repay.

Marc Pfeiffer, assistant director at Rutgers University’s Bloustein Local Government Research Center, says the money Lakewood is borrowing represents a shortfall in the funding system.

“The district doesn’t owe anybody that money. That money is a result of deficits in the district’s budget,” he said.

A district in ‘fiscal distress’

Both the courts and the state auditor agree that the state’s school funding formula has failed the district.

“Lakewood school district may be considered a district confronted by severe fiscal distress and could benefit from the creation of an additional state aid category,” state auditor David Kaschak wrote in a July report.

The report, obtained by the Asbury Park Press, pins much of the district’s financial problems on its high percentage of special education students, as well as transportation costs for nonpublic school students.

The report also laid some blame on the district’s Department of Education-appointed monitors, who have been in place for nearly 10 years and received nearly $1 million in salary from Lakewood taxpayers.

“Despite the assignment of four state monitors with total salaries of $936,667 to provide fiscal oversight, the district continues to experience fiscal issues,” the report said.

Lakewood’s Republican state legislators, Sen. Robert Singer and Assembly Members Sean T. Kean and Edward H. Thomson, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

But when asked about the auditor’s report in August, Singer did agree that a new formula was needed. “We have no option but to do this,” he said then. “We have asked to change the formula. This explains why it has to happen.”

Lakewood leaders are just as upset at the lack of state aid as the district and say changes are needed.

“The funding formula for Lakewood just doesn’t work,” said Mayor Ray Coles. “It is a very unique district. I think the folks at the state level are waking up to the fact that the school district is more than the kids in the public schools.”

Rabbi Moshe Zev Weisberg, a former township committee member and spokesperson for the Lakewood Vaad — an influential group of Orthodox Jewish business and community leaders — said changes in the state approach are needed.

“With the funding deficit and having to go every year, hat in hand, to try to put a Band-aid on it, we would want to have a permanent solution by now, which the courts have said is necessary,” Weisberg said. “I think we have heard over and over again it is a revenue issue not a spending issue. The nonpublic school students in Lakewood are invisible in the formula. We need a permanent fix, ... we are fooling ourselves.”

Changes needed, but delayed

In March, a state appeals court ruled that Lakewood public schools do not receive adequate state funding. The appeals court declared that the district is “severely strained” by its obligation to provide transportation and special education to thousands of nonpublic school students.

The appeals court decision relates to the nine-year-old Alcantara case, a lawsuit filed by Paul Tractenberg, a former Rutgers law professor and founder of the Education Law Center, and attorney Arthur Lang, a Lakewood High School teacher.

Their complaint challenged the state’s funding, claiming the district’s legal obligation to provide transportation and other services to more than 40,000 nonpublic school students required more state aid.

In the decision handed down on March 6, the three-person appellate court declared that Education Commissioner Angelica Allen-McMillan must review the district’s situation and come up with a way to improve its funding. But it did not include a deadline or a more detailed requirement for how to proceed.

Allen-McMillan said last month the state was only now beginning a review of the district’s school finances to formulate a solution. She did not promise that the state would provide more aid, or a different formula, at the end of that review.

“This is only a preliminary estimate as the volume of information to be reviewed and complexity of the required analysis are unknown at this time,” Allen-McMillan wrote in an August 22 letter to Tractenberg and Lang.

The Department of Education and Gov. Phil Murphy’s office declined to comment, citing the ongoing litigation.

MORE: Lakewood $1M school board attorney monthly fees shrink after APP report

Unique transportation dilemma

Meanwhile, the nonprofit consortium that oversees busing for Lakewood’s private school students has had to borrow $2 million from the township to meet its costs through the end of 2023.

The Lakewood Student Transportation Authority requested the loan to “tide it over” until early 2024.

“This is just to get us through the next several months,” said Avraham Krawiec, director of the authority, which began in 2016.

Under a state law created specifically for Lakewood, the student transportation authority arranges busing for nonpublic school students who attend private school.

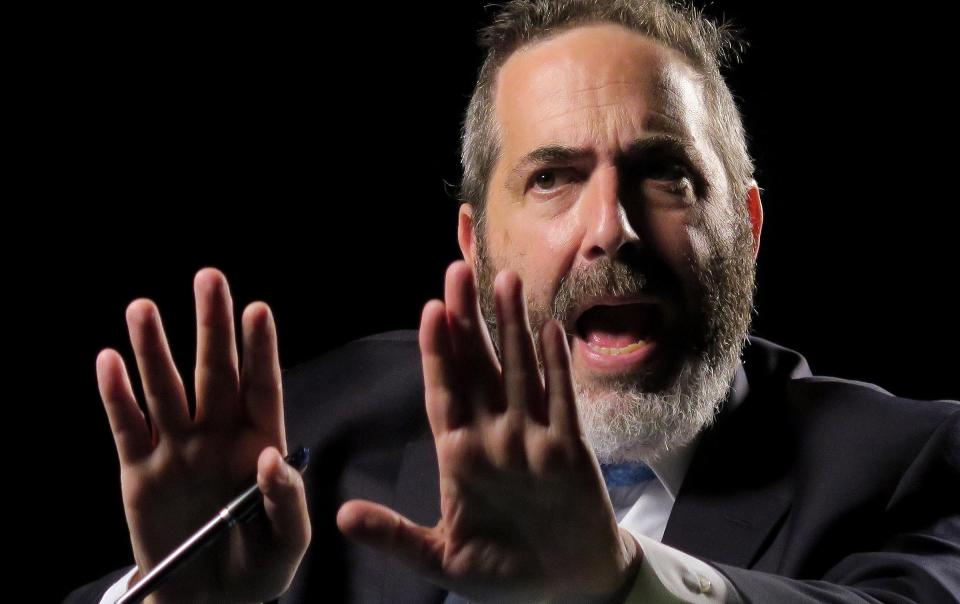

More than $25 million in state grants has been provided through the Lakewood Public School District at a rate of $710 per student, according to district spokesman Michael Inzelbuch, who also serves as school board attorney.

But the actual annual cost for each student to be transported by private companies can be as much as $1,165, with the difference covered by the district.

MORE: Lakewood school bus agency needs $2 million township loan to keep going

The district must also pay for busing students across so-called “hazardous routes,” which are deemed by police to be dangerous due to highways or areas lacking safe sidewalks.

The transportation authority also serves about 5,000 students whose busing is not mandated or subsidized, but paid for by the families who live within the walking limits but choose to bus their children.

That means the Lakewood authority is expected to transport about 50,000 students, more than the entire K-12 student population of the city of Detroit last year.

The local authority is expecting at least 2,500 more nonpublic students this fall compared to last spring, sparking a higher cost to the agency.

The additional state funding for the Lakewood transportation authority to match the higher population will not be provided until January because the state needs to verify the number of students being served this fall, officials said.

MORE: Lakewood Schools tighten scrutiny of school bus companies

$53 million in special ed costs

Then there are the special education students with extraordinary needs that can’t be met in-district and are required to be placed in specialized, out-of-district schools that could better serve them.

In Lakewood, the special education enrollment is large — and growing.

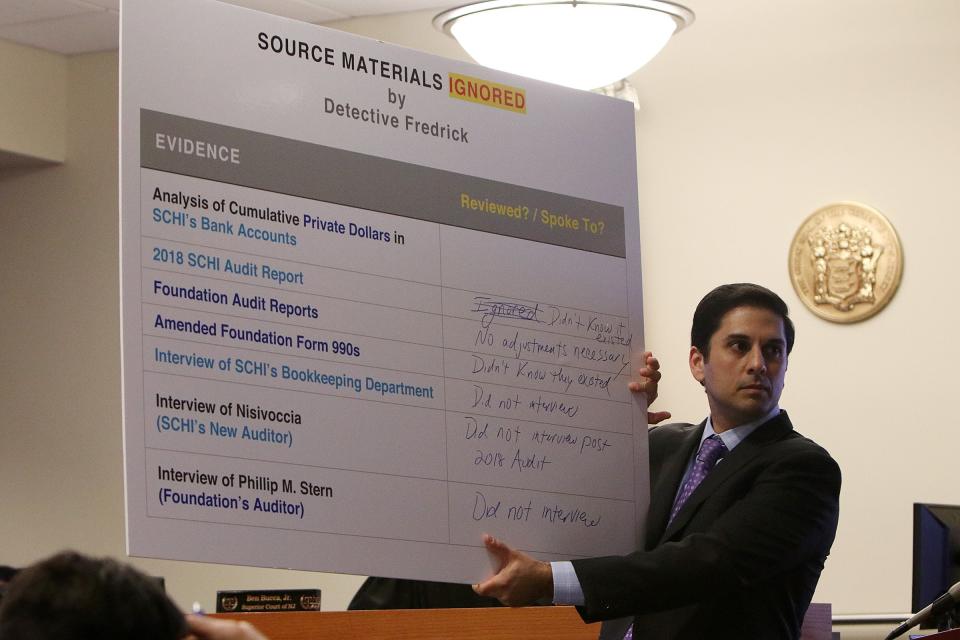

In the case of Lakewood public schools, the district sends most of its extraordinary special education students to the School for Children with Hidden Intelligence, locally known as SCHI.

Recent state data shows SCHI, a registered nonprofit, has an annual tuition rate of approximately $123,000, while the average annual cost of private schools for children with special needs in Ocean and Monmouth Counties is $85,000.

According to SCHI’s most recent tax return, 80% of its revenue came from public school placements.

SCHI officials declined multiple interview requests.

MORE: Why Lakewood SCHI founder, sentenced to jail in 2019, hasn’t spent a day behind bars

District records show that for the coming school year, 398 public school special ed students, or 8% of all district students, will be placed in private schools. In comparison, neighboring Jackson and Toms River Regional districts are each sending less than 1% of their students to private special education schools.

The number of students that Lakewood sends to private special education schools is remarkably high, said Stephen Genco, director of the K-12 education program at Georgian Court University, who served as superintendent in various area districts for over 10 years.

Typically, a child study team from the district along with the child’s parents determine if a student needs out-of-district placement regardless of how expensive that might be, he said.

“It shouldn’t matter how expensive (the school is) because the child's needs come first,” Genco said.

The auditor review stated that Lakewood’s special education costs are among the highest in New Jersey, noting that 33.4% of students are classified as “special education,” the second highest in the state and more than twice the state average of 15.9%.

In addition, Lakewood’s transportation costs for nonpublic students are more than $9.7 million, well above the second-highest district, Teaneck, in Bergen County, which spends $760,000.

A history of borrowing

The pending loan of $93 million would be added to Lakewood schools’ current debt of $123 million in state aid loans dating back to the 2014-5 school year when it first borrowed $4.5 million.

The district also borrowed $5.6 million in 2016-17; $8.5 million in 2017-18; $28.1 million in 2018-19; $36 million in 2019-20; $54.5 million in 2020-2021; and $24 million in 2022-23.

Currently, Lakewood has the highest outstanding state loan balance. Lyndhurst school district in Bergen County has the second highest at $2.9 million. There’s no interest charged on state aid loans and loan payments are automatically deducted from the school district’s state aid payments.

“The state can basically grant them amnesty on it and say at some point, you don't have to pay it back, which is effectively having given them that total sum of money in extra aid over the years,” said Pfeiffer of Rutgers.

Are local actions working?

But as the district cries poor, demands a change in the state funding formula, and seeks tens of millions of dollars in loans each year, it is also offering up increased pay for its highest administrators.

And while its proposed 2023-24 budget of $264 million represents a 30% increase over last year’s spending plan, it includes a property tax decrease even though the state allows districts to raise taxes up to 2% annually.

Inzelbuch, Lakewood School Board attorney and district spokesperson, earns more than $800,000 annually, while Superintendent Laura Winters recently received a contract extension through 2028 and a salary hike of $22,000 to $238,000 for this school year, along with a 3% raise each year after.

“We need to put everything in perspective,” Inzelbuch said via email when asked about the continued loan requests and spending increases. “Most importantly, the kids of Lakewood public schools are receiving a thorough and efficient education.”

Juan Carlos Castillo is a reporter covering everything trending. He delves into politics, social issues and human interest stories. Reach out to him at JcCastillo@gannett.com

Joe Strupp is an award-winning journalist with 30 years’ experience who covers education and several local communities for APP.com and the Asbury Park Press. He is also the author of three books, including Killing Journalism on the state of the news media, and an adjunct media professor at Rutgers University and Fairleigh Dickinson University. Reach him at jstrupp@gannettnj.com and at 732-413-3840. Follow him on Twitter at @joestrupp.

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: Lakewood School District needs $93 million to keep doors open