Larry Jackson Jr., entrepreneur and creator of Black Visitor’s Guide to KC, dies at 76

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Some 30 years ago, few knew Kansas City’s Black business community better than Larry Jackson Jr.

The lifelong city resident and bootstrap entrepreneur was a “walking Rolodex” of the day’s places and faces, his son, Scott Mason, 53, said. “If you needed X, Y or Z, he could usually rattle off a couple names.”

Jackson could tell you where to go to get a haircut, a fine meal, a bag of groceries — anything — from a Black person.

He understood, too, what it meant to run one of these storefronts. In the 1980s, he and a friend opened JAM Distributors, a wholesale beauty supply shop on Minnesota Avenue in Kansas City, Kansas, that, according to a newspaper clipping saved by the family, kept the “contemporary Black woman and her needs in mind” with brands like Ultra Sheen, Posner’s Lusters and Lustrasilk. The name represented the combination of his last name with that of his co-owner, Lloyd Mason Jr.

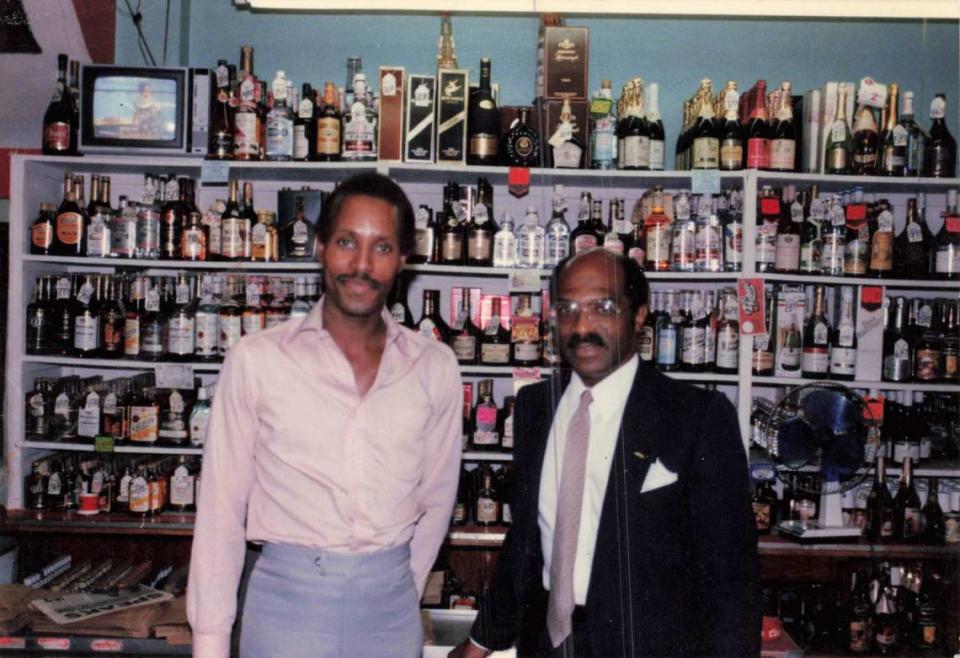

This was far from Jackson’s only venture: He was also a concert promoter, using his knack for writing to get out radio ads on big acts coming to town like Roy Ayers and The Jackson Five. He was the owner of a liquor store, Jackson Liquors — once owned by his father — in the 1970s and 80s; then, in the early 2000s, a convenience store called Basic Commodity Merchandisers.

Jackson, who died on June 10 at the age of 76, “knew how to get from A to B” when launching a business, taking big, bold swings and putting in the work to see his ideas through, Mason said.

He did some of what he considered to be the most meaningful work of his career at the marketing firm he started in the early 1990s, named SEDIC (Specialized Entertainment and Distribution Inc.).

Headquartered in the Lincoln Building at 18th and Vine — a historic center of Kansas City’s Black culture — the company produced campaigns for brands as large as the Missouri Lottery, Budweiser and Sprint, Mason said.

Black Visitor’s Guide to Kansas City

But the project that perhaps best exemplified his ambitions was smaller, highlighting the hardworking colleagues of his home: The Black Visitor’s Guide to Kansas City.

The visitor’s guide, produced in partnership with Kansas City’s tourism department, was a pamphlet featuring a comprehensive list of Black-owned businesses, Mason recalled. Residents could pick them up in the Lincoln Building, or from newspaper stands across the Kansas City metropolitan area. For people of color, they were like a blueprint for navigating a community that was deeply segregated — and still is.

Mason sees the visitor’s guide as his father’s effort to fill a “market niche,” giving out-of-town visitors a handy reference they “could pick up and quickly thumb through and identify some different minority-owned businesses.”

Damon Jackson, another of Jackson’s three sons, said his father was driven by a desire to help his friends.

“I think he just really meant to do something for the community,” the 45-year-old said. “At the time, there wasn’t a list, or a place where you can go and find Black businesses.”

Mason has spent the past few weeks scouring every inch of his home for a copy of the guide. So far, no luck. If he closes his eyes, he can still see it — A skinny thing, about six or eight pages, with a reddish cover and big black text. It was filled with pictures and short descriptions.

To those who knew Jackson, the guide was a perfect representation of who he was, distilling his life-long love of his community into a neat little brochure. Around his neighborhood, he was a gregarious presence, Mason said; he would say hello to every single person he passed on the street, smiling and charming and “schmoozing.”

The people on his block had always been closer to family, ever since he was a kid, Damon Jackson said. Growing up an only child, with almost no relatives to speak of, he used to refer to the adults as aunt or uncle. A school friend could be like a brother.

“He knew everybody,” Damon Jackson said. “Everybody knew him.”

‘That entrepreneurial bug’

Born December 16, 1946 in Kansas City, Kansas, Jackson grew up an only child. His father operated the liquor store on 13th Street and his son took an early interest in the business.

He also loved basketball; after entering Wyandotte High School, he became a key role player, working with star Lucius Allen — who went on to have a historic NBA career — to win the Class AA State Championship in Kansas in 1964.

If basketball taught him to be a part of something, to work together toward a common goal, his father taught him the importance of being strong and independent.

“I think he got it from his father,” Damon Jackson said. “He kind of had that entrepreneurial bug about him; he always wanted to do his thing.”

Larry Jackson Sr. died in the mid-1970’s, leaving his second-eldest son the liquor store to run. Jackson had three boys of his own at the time, raising them as a single father, constantly worrying what would happen if the profits began to dwindle. He felt he “couldn’t just let the proceeds sit there,” Mason said. He took his income and invested in new ideas.

His various ventures — from beauty, to advertising, to food and convenience — were the result of a lot of research and a lot of learning-by-doing. He was sort of like a “serial entrepreneur,” Mason said: He would try something, put everything he had into it until it petered out, then move on to the next thing. But business, of course, wasn’t his entire life.

He loved people, and majored in psychology at Park College. He was an advocate for civil rights, marching and demonstrating alongside activists like the late Rev. Fuzzy Thompson, once the executive director of the Martin Luther King Urban Center in Kansas City.

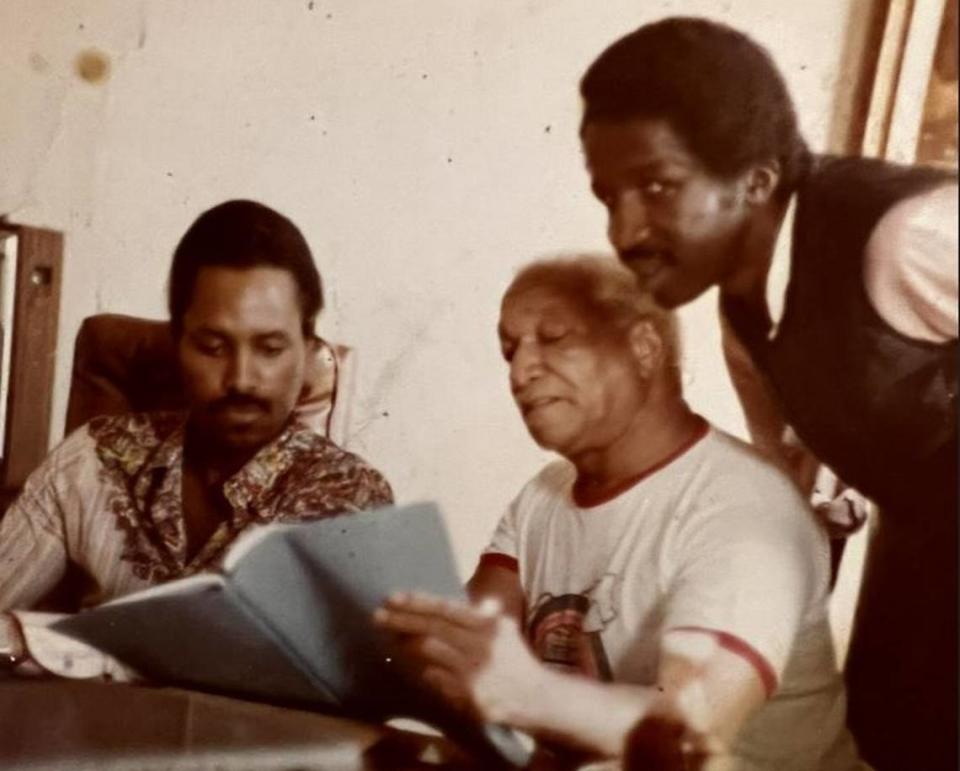

Writing was a passion, too; Jackson moved to Los Angeles briefly after college to try to write for TV shows, one time meeting the actor Redd Fox. A family photo shows the two hunched over a thick blue script.

In his 50s, Jackson took on an entirely new career — he became a substitute teacher in the Kansas City, Kansas, school district, working with kids of all ages, eventually focusing on students with special needs. He had a lifetime of learning to draw from.

“I think he used it as an opportunity to teach them some lessons — life lessons,” Mason said.

After he died of pancreatic cancer earlier this summer, some former and present staff of KCK schools showed up to his funeral, held June 24 at Thatcher’s Funeral Chapel. They recounted the effortless connection he had with the kids. They discussed how, by raising his voice, he helped substitutes in the district secure their retirement benefits.

Jackson was a favorite of many principals, and served long stints at certain schools when teachers became sick. He “had a way of connecting with kids that was unique to him,” Mason recalled. He was warm and patient.

Entrepreneurism, the thrill of starting something new, was a big part of who he was.

Really, though, it was always about people. And home.

“This is really the only community he ever knew,” Mason said. “He was always connected.”