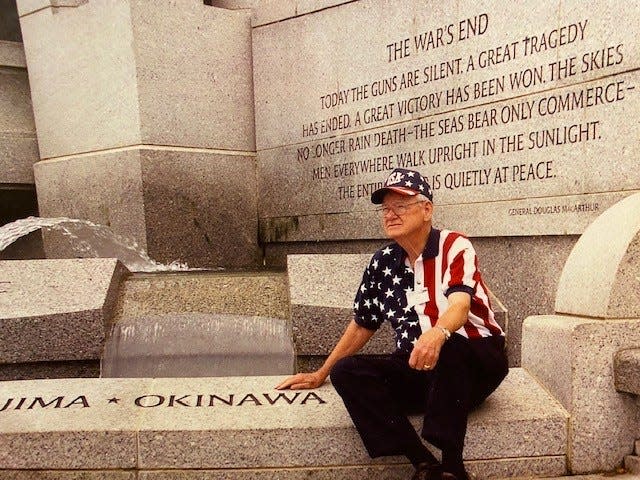

The last battle: Sudan native recalls fighting on Okinawa during WWII

Joe Shuttlesworth had no way of knowing it at the time, but the then 19-year-old Marine was about to engage in the last major battle of World War II.

Now 97, the Sudan native recently recalled the 81 days he spent on the on the Pacific Island of Okinawa.

The island, just 350 miles from mainland Japan, was only 466 square miles of dense foliage, hills, ravines, and trees. It was to be the site of the last stand of Japan’s 32nd Army, some 130,000 strong. They awaited the arrival of the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet and more than 180,000 U.S. Army and Marine Corps troops. Among them was Shuttlesworth.

Shuttlesworth was born “in an underground home” where his family resided in Sudan, Texas. His father, James Marshall and mother, Birdie Lee arrived in West Texas from Alabama in a covered wagon. The house was eventually built over the dugout and had 13 rooms which Birdie rented out to help make ends meet. Joe was the last born of seven siblings.

“This was during the Depression - It was hard to feed a family that large,” he recalled. “I had a rifle when I was only 8 years old. I would sit outside the barn and shoot the mice when they would come out. I became pretty good at it. I attended school in Sudan. I played basketball and football. I hurt my neck trying to tackle one big old country boy 50 pounds heavier than I was. My neck always bothered me.”

Graduating from high school at age 17 in 1942, Joe tried to volunteer for the Coast Guard.

“Dad wanted to ‘keep me out of (the war),'" Joe recalled. “I had one brother in the Army and one in the Army Air Corps. When I turned 18, I got my draft notice and went down to the courthouse in Lubbock to sign up, take exams and a physical. Three Marines came through and asked for volunteers. Everyone was quiet as a mouse. No one wanted to join. Finally, they called me and two other local guys up and one of the Marines said, ‘We have selected you to join the Marines!’ So, they sent the three of us to El Paso on a bus. We waited in a hotel room for three days before being inducted.

“We finally got signed up and were sent by train to San Diego for eight weeks of basic training. As soon as we got off the bus, they started yelling at us and later cut all of our hair off. We wound up doing 10 weeks of basic. I qualified expert marksman and thought I was going to be a sniper. After that I was told to be a telephone guy. I learned how to climb a telephone pole with spikes on my boots."

During his time there, he recalled training with a group of Navajo Native Americans who were going to be code talkers.

"We had to jump off a tower into the pool, fully clothed, take off our shoes, socks and pants and tie the pants up to be used as a flotation device," he said. "That was hard to do! The Navajos refused to do it.”

It’s estimated that the U.S. Marines used over 400 code talkers during WWII. The Japanese were never able to break their code.

After training, Joe was assigned to the 1st Division, 7th Marines, 7th Regiment. He and his fellow Marines boarded the USS General Harry Taylor and headed for the Pacific. When they passed the equator, the sailors and Marines onboard ships became card carrying Shellback members. That tradition (in the U.S. Navy) dates back to at least 1775.

“The ship was so full of men that I slept topside on a cot under a hanging smaller boat. It rained so much that my boondockers (boots) were full of water," Shuttlesworth recalled. "I went below to get a set of dry ones from the storeroom which was guarded. I finally convinced the guard to give me new boots, but they were way too small. I always had trouble with my feet after wearing those. We stayed in Guadalcanal and did jungle maneuvers for 10 days.”

The date to invade Okinawa was called Operation Iceberg and was set for Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945.

“We were brought in on amphibious boats," Shuttlesworth said. "The invasion was so noisy, you couldn’t talk to anyone, you had to just keep moving. The big guns from our ships were going off and you could see the large shells flying through the air towards their targets on the island. We were put on shore with the Navajos. I could read (American) code, so my job (as a message center man) was to take a coded message from the regimental commander to the Navajos on the front line with my radio and they would relay the message to the troops on the frontline. I was going along a trail when someone yelled at me. It was Colonel Gormley (later promoted to General). He told me, ‘Don’t go up there, there is a Japanese sniper on the trail up ahead and he’s been picking off our men. The Japanese were always bombing us, so we moved from place to place and would dig a hole with a buddy in the hole next to you that you shared."

He said one of his duties when the island was secured was working in a large tent.

"It was so hot in there that I passed out and must have hit my head on a rock," he recalled. "When I woke up, a medic was treating me, but I don’t know what he gave me. He said he ‘had to move on.’ He didn’t make a report of that incident. Also, one night, a major in a neighboring tent was killed by Japanese artillery.

“If you were wounded or hurt, they would put you in a small boat and take you out to a hospital ship. I saw dead marines stacked up at least six feet tall.”

The bloody Battle of Okinawa finally ended on June 22 after the Japanese commanding Generals Ushijima and Cho committed suicide. The casualties were staggering: American forces suffered 45,000 casualties including 12,500 killed. Japanese deaths were estimated at over 100,000. The battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa helped convince President Harry S Truman to approve use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

Joe said, “We were waiting in Okinawa to go to (invade) Tokyo. They kept putting us off and didn’t tell us anything about the bomb.”

Not long after the Japanese surrender, on Sept. 26, 1945, Joe’s unit was sent to Tangku, China and accepted the surrender of the Japanese there on October 6, 1945. After returning to the states in April 1946, Joe was discharged from the Marines on May 6, 1946.

Joe worked for a time near San Francisco in a cannery and an oil refinery. He returned to Sudan and met pretty young Zell Dean Harris in the local grocery stored owned by her dad. The first time he met her he said, “I’m going to marry you.”

Shuttlesworth recalled her saying she, “wasn’t going out with someone like him.” Joe finally “won her heart over by asking her to go for a Coke."

They married in April 1947. They had two sons and one daughter. Joe eventually bought a small store of his own in Goodland, (south of Muleshoe) for two years. They moved to Wolfforth and Joe attended Texas Tech and got his degree. He would work for Furrs Grocery Store for 40 years.

Zell Dean died in July 2002. Joe eventually married Billie Pectol and they now live at the Southhaven Assisted Living facility in Lubbock. Joe, never one to be idle said, “You can come here to die, or you can do something to keep yourself busy.” True to his word, Joe is “still busy” at age 97 building colorful birdhouses which he builds onsite and gives one away to the winner of the weekly bingo games. Joe A. Shuttleworth – a survivor of 81 days on Okinawa and life

This article originally appeared on Amarillo Globe-News: The last battle: Sudan native recalls fighting on Okinawa during WWII