The last picture show

On a late January evening in 2023, as the end titles for the 2022 summer rom-com “Ticket to Paradise” rolled down the movie screen, nine patrons made their way out of the 550-seat auditorium, doing up coats in preparation for braving Tooele’s snow-laden Main Street. Ritz Cinema co-owner Mickie Bradshaw stood in front of a fireplace chimney to the side of the lobby, waving at the few familiar faces of longtime cinemagoers, before returning to her thoughts about the fate of the 84-year-old movie house.

Attendance at the theater had been dire since it had reopened 10 months after the pandemic began in Utah. “We are going to have to decide this summer whether to close or not,” she said.

As if in response, a deep, vibrant moan sounded within the wall. Bradshaw stepped away from the chimney, brushing at her shoulder for a moment, as if dislodging an unwanted speck of dust. “The ghosts don’t like to hear that,” she said, her sad smile tinged with irritation. “People bring ghosts in with them all the time,” she added, her 9-year-old dog Bo Peep wandering around her feet.

Alan and Mickie Bradshaw have worked at the Ritz all their lives. At 71, Alan Bradshaw was ready to call it quits. He’d had open heart surgery in 2021. “I’ve been working here since I was 11. So 60 years, that’s a long time.” His wife was more reluctant to turn her back on a theater and a building she felt was a part of their family’s emotional fabric.

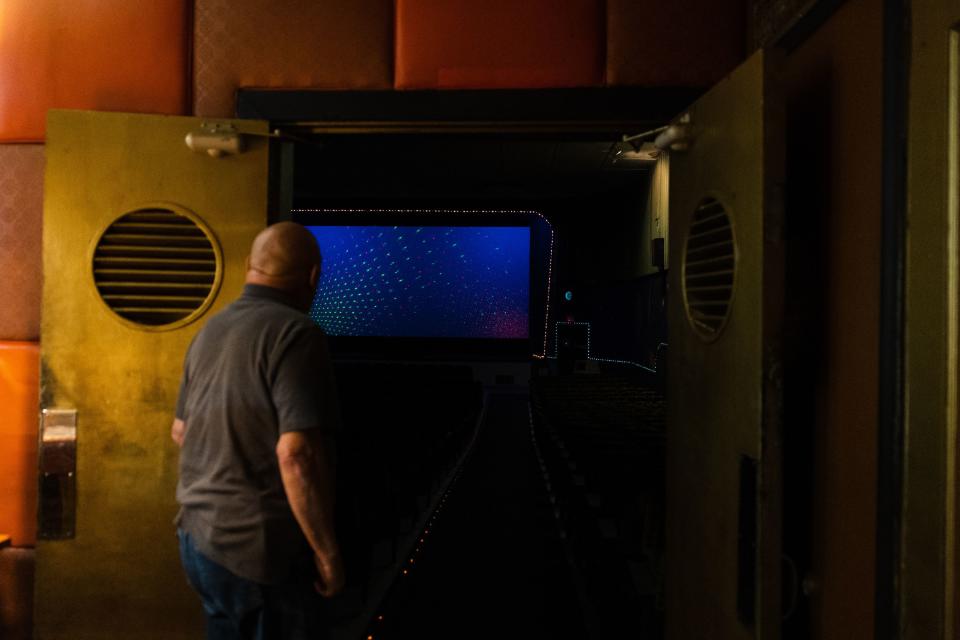

As time capsules go, the Ritz is a doozy. The early 1960s spray-painted mural that covers the auditorium’s side walls celebrates the dawn of the space race. The “cry room’s” dozen seats await nursing mothers so they can comfort squalling babies and watch the film without disturbing others. The male toilet has a decades-old stencil of a seated man leisurely smoking. But as much as the Ritz wore its years nonchalantly on its sleeve, it also had its more contemporary idiosyncrasies. If you lingered after a film ended, you might hear a leaf blower kick into gear as an employee ushered spilled popcorn along the aisles.

What brought the Ritz to its knees was a too-common story for independent cinemas across the United States. First a multiscreen cinema opened in 2000 a few miles away, siphoning off much of the Ritz’s business. The Ritz weathered that challenge by becoming a second-run or discount movie house. Then in the early 2010s the studios insisted cinemas switch to digital movies, with massive initial costs, even as the dominance of smartphones fundamentally changed viewing habits. With the pandemic and the global closure of cinemas, it was hard to imagine fate had any more catastrophic developments in the wings. But the most decisive blow, the Bradshaws said, was yet to fall.

“The studios were the goose that lays the golden egg,” said Alan Bradshaw. “They’d make the movies, release (them) in theaters, build up interest, go to second- and third-run theaters, and then be released on VHS or DVD, before going to TV. And the big companies said, ‘You know what? We’re just gonna send the movie straight to the family.’”

A lifelong loyalty

According to cinematreasures.org, there are currently 81 cinemas in Utah showing films, out of a historical total of 326 movie theaters. Of that 81, just under half are small-town independent cinemas located outside the Provo-to-Ogden corridor, with one or several screens to their names.

For those that have survived this far, the question dogs them: do the economics of small town cinemas still pencil out? Trevor Shriner, whose family owns a five-screen cinema in Vernal, thought so. His business in late spring 2023 had seen a sharp uptick in patrons compared to the year before. “A quote I hear in regards to streaming,” he wrote in an email, “is, ‘Everyone has a kitchen and we all like to eat out.’”

Survival was still possible, argued Codi Kruse of Clark Film Buying, albeit if theater owners were willing and able to adapt. Clark Film Buying represents 150 independent cinemas in their negotiations with studios to rent their films.

Movie houses were once essential to the thriving of small communities, she said. “They are the only entertainment options around for small towns. They need to remind locals this building is the heart and soul of your community, come here and experience it.”

Some, Kruse said, had heard their movie house’s call for help and rallied. “There’s been changes in ownership, with conversion to privately owned cinemas bought by wealthy benefactors, or to publicly owned cinemas bought by a city or community. Those involved know they will be running their purchased theater at a loss.”

If the Ritz’s owners didn’t have the money or energy to reinvent themselves, they still could lay claim to the eccentric passion for their cinema that so many in the independent movie house world display.

Their employees, their audience and their building all mattered to the Bradshaws. “A lot of our customers keep coming back until they die,” Mickie Bradshaw said. At the start of 2023, they lost another regular to cancer. That was why she preferred not to know their names. It made each death all the more personal. “My employees, the public, I take care of them. It’s part of me, it’s part of us, but we are worn out.”

The world of independent cinemas is about sacrifice and family, said Kruse. “You give so much of yourself to these jobs. You give up nights, weekends.” Even her own role, she said, reflected how she had inherited her father’s passion for supporting small town cinemas. “My dad started this company and here I am carrying on. It does lend itself to this idea of a legacy business.”

Tooele’s downtown district recently joined the national Register of Historic Places, opening the door to tax credits for downtown property owners interested in preserving and improving their piece of the neighborhood. The listing, however, did not protect registered buildings from being torn down. Mickie Bradshaw hoped that in the remaining months before summer a white knight might yet emerge to save the Ritz as a cinema. “We would love for somebody to come in and do what we do. Love her and take care of her and keep her open. But nobody can because it’s not making any money.”

A house with no eaves

Turn off I-80 West for Tooele and it’s a long drive past gas stations, cookie-cutter subdivisions and strip malls. It’s not until you hit downtown Tooele and landmarks such as the Ritz marquee at 111 N. Main Street that you feel you have found the town itself.

The Ritz theater was opened in 1939 by businessman Sam L. Gillette, followed by the Motor-Vu drive-in after the war. Alan Bradshaw was 11 when in 1962 his father, Ralph Bradshaw, sold their half of a drive-in they co-owned with Gillette in Tucson, Arizona, to their partner and bought from him the Ritz and the Motor-Vu. Alan Bradshaw grew up working in the Ritz, standing on milk cartons every 20 minutes to change the reels of 35mm prints on the projector.

Bradshaw’s family’s ownership of the town’s leading source of entertainment did not make life easy for him. His father would throw out rowdy kids, banning them for 30 days. The next day at school, the aggrieved teens would look for him. “I’m gonna bat your ears for you,” a kid would announce. Bradshaw quickly learned to stand his ground.

Two years after the Bradshaws took over the Ritz, 12-year-old Mickie Carter came to work there. Her father wanted to bring her out of herself, he’d told Ralph Bradshaw when he asked for a job for his bashful daughter.

At high school, Bradshaw and Carter briefly dated but sparks didn’t fly. Bradshaw went to college and then on a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to Canada and Minneapolis. When he returned, his engagement to his high school sweetheart ended. Carter was about to marry someone Bradshaw did not approve of, so he made a counter-offer. She turned him down, but a day later had a change of heart.

“She decided she’d give it a try anyway,” he said. “So it clicked.” They were married Jan. 19, 1973, in the Salt Lake Temple.

From the beginning, the Bradshaws were comfortable standing out in their community, despite Mickie Bradshaw’s shyness. Every summer, Ralph Bradshaw had made Alan get on a ladder and scrape and paint all the eaves on their home. “I swore my house would never have any eaves,” he said. “And my house has no eaves.” Shortly after they married, they built and moved into a geodesic dome, located next door to the Motor-Vu drive-in.

Alan Bradshaw shrugged. “Guess I’m just different,” he said.

He got a well-paid job at National Lead Co. and, when they could, he and his wife worked at the cinema and drive-in. But it wasn’t long until his father asked him to take a salary cut and help him run the family business full time.

Celluloid Christmas dreams

Alan and Mickie Bradshaw had four children and from the beginning, all of their lives were intertwined with the movie business.

When Mickie was pregnant with their first, she almost delivered at the drive-in. After the baby came, “we put him in a kind of cut down box on a little blanket right next to me and I took care of him while I worked.”

Cherie Black was the youngest. For her, the cinema was a second home where she could have fun and bring her friends. “It’s always been a part of me. It was a place to gather, to escape, to go with your friends into an imaginary world.”

Her favorite time was the day before Thanksgiving when the big holiday-themed movie would open, like Pixar’s “Toy Story.” It felt magical to her to go outside in the snow and look up at the movie title in the bright yellow marquee lights and have goosebumps at the festivities yet to come.

Along with pleasure, however, the children were also expected to work. It was labor that came with its own education. They learned to add and subtract from working the concessions stand. They learned to greet people and be courteous, although Saturday children’s matinees left them as adults with a lack of fondness for the hijinks of children.

Black worked the Ritz from 12 to 19. She manned the concessions, made popcorn and sold tickets from the street-side ticket-office booth. She would hire people and escort unruly cinemagoers to the door.

Working at the Motor-Vu drive-in, Black said, was starkly different. They cooked hot dogs, hamburgers, pizza and nachos. The children had to mop, sweep and empty the garbage. When they sold tickets, they would check the back of vehicles to make sure filmgoers were honest about their head count. Black would radio her father to eyeball a vehicle she thought held more people than they paid for.

“If we caught them, they had to pay triple,” said Black.

Discounted tickets

For 60 years, the Ritz was a first-run movie house, meaning it contracted with distributors to show any movie they put out when they were released. That came to a halt when competition came to town.

When word got out that a six-screen cinema would be opening five miles away from the Ritz, Black saw a change in her father and grandfather. “You could feel it, see the fear of the unknown in the faces of my dad and my grandpa, the worry they wouldn’t be able to operate the theater much longer.”

At the end of the 1990s, Ralph Bradshaw, who was battling cancer, and his son Alan hired Montana-based Verl Clark and his company, Clark Film Buying, to, as Alan Bradshaw said, “dicker with (studios) about what I could play.” Back then Clark had 250 independent movie house clients.

Up until the last week of his life, Ralph Bradshaw would go to the Ritz, take his place on the couch by the fireplace and greet filmgoers as they came in. When he died in November 2001, the family screened home movies and had a buffet-style meal laid out in front of the screen.

Alan Bradshaw realized things would have to change. “I am just a little guy. What am I going to do?” As the lesser-grossing theater, he would have much less negotiating power with the studios than his new neighbor. His accountant and bookkeeper told him the best option would be discount movies. “Then I could play almost anything I wanted that was older.”

The death of second-run movie houses

To Alan Bradshaw’s surprise, becoming a second-run movie house worked out. Initially he sold tickets for $1.50. They had so much product to choose from they could play two movies a week on each screen — they converted a driveway into a second screen in 1978 — and change them fairly often. Large families found the mix of cheap tickets and concessions an attractive option and regularly returned. “They felt like they could make a whole night out of it,” Alan Bradshaw said.

The drive-in still showed first-run movies and each summer the Motor-Vu’s earnings helped subsidize the Ritz. “We earned enough in the summer to carry us through the winter,” Alan Bradshaw said. Patching it all together, somehow the Bradshaws made it work.

A new threat emerged in the early 2010s, when studios announced they would move from sending out film prints to digital. Cinemas had to purchase digital projectors that cost between $50,000 and $100,000 each.

For some small theaters which grossed annually around $30,000, such costs were prohibitive and they closed. The Bradshaws weren’t ready to give up. They struggled to gather the funds to switch to digital. A local fan organized a GoFundMe campaign that garnered $700 and a Tooele resident who worked for a Salt Lake film distributor got them a discount on a digital projector.

Right up until the end of 2019, recalled LaDawn Tracy, who rented the upstairs apartment above the cinema for the last 10 years, business was often brisk at the Ritz. On weekends, seeing the long lines from her window, she would go downstairs to help with tickets and concessions.

By the time the first COVID-19 cases appeared in Utah in March 2020, the Ritz had shown movies every single day from its opening in 1939. That ended when several Utah Board of Health employees came into the lobby and informed the Bradshaws they had to close the cinema down. All of the 150 locations Clark Film Buying represented also shuttered their doors. “That was a terrifying time for everybody,” Kruse said.

The Ritz was closed for 10 months.

“After COVID a lot of people didn’t come back here,” Tracy said. “They didn’t leave their houses to go to the movies anymore. Live streaming basically killed it.”

Kruse agreed. “The biggest impact of streaming has been that discount movie prices aren’t as desirable as they used to be when you can watch the same movies on streaming. It’s really killed the secondary market for theaters.”

The final blow to the Bradshaws was a 2021 property tax hike that left them no choice but to sell the Motor-Vu drive-in. The 2022 sale proved a turning point. “When they sold the drive-in, it was like they were giving up a child,” said Black, their youngest. Alan and Mickie Bradshaw had different reactions to the sale.

Alan Bradshaw had fought long and hard to keep the Main Street movie house going, to the point of not taking out a paycheck for years, his wife said. Now he was ready to call it quits. Paradoxically, Mickie Bradshaw, who had been ready to move on from the theater for years, after saying goodbye to the drive-in felt a fierce protectiveness for the Ritz.

“My mom really wants to see it continue, to be a theater, to be what it’s been, but the reality is, I just don’t think it can,” Black said. “They are not making anything. It’s almost like a handout, a charity right now for people to come.”

Faith in community and Hollywood

Kruse did find one upside to the pandemic for rural cinemas. “With people stuck at home, they really missed the socialization, the going-out.” The public craved movie theater popcorn. “We’re social creatures, we want to be out in a group, I think people remembered that.”

She argued that as more and more distributors of content came online it “fractured the ecosystem. People were overwhelmed. ‘Where is my streaming service? Where do I find a movie I want to watch?’ Theaters offer a nice convenience to that.” In the very act of showing a film, they elevated it to a celluloid event, rather than part of an endless stream of content.

Trevor Shriner is betting that small-town cinemas do pencil out, at least in Vernal. He owns the first-run movie house Cinemas 5. It’s the latest iteration of a three-generation theater business that in 2014 Shriner quit the oil and gas industry to take over managing from his father. Shriner credited his wife, who does the bookkeeping, with keeping the business going.

Shriner’s faith was partly in the support and care his community showed his business, one that he reciprocated with scholarships, donations and events to support community members.

That faith was born out in spring 2023, when April through May saw 1,100 more patrons than the same two months the year before. His belief in the economics of small-town movies was also based on the films themselves. He argued that the uptick in audience attendance was driven by better movies.

“I don’t think we’ll ever get back to where we were, but we’ll get back to better than it was the past couple of years. And as we’re going forward, I see nothing but better movies, better quality of movies and quantity.”

Investing in the future

For those discount movie house owners, like the Bradshaws, who can’t keep their business going but don’t want to see it close, sometimes, as in the Gem Theater in Panguitch, near Bryce Canyon, a white knight does emerge.

In September 2020, in the teeth of the pandemic, the Kaspar family bought the first-run theater from a local owner. The Gem, which opened in 1909, was originally a theater. When the Kaspars acquired it, the cinema had been remodeled after sitting vacant for 12 years following a fire in the 1980s that burned the cinema down to three walls, but left the marquee untouched.

Roger and Ruth Kaspar live in California. On Ruth’s side, the family claimed deep roots in Panguitch. One of her maternal ancestors had bought the land the cinema sat on. Her grandmother played the organ during the silent film era at the Gem. Her pay was five movie tickets a week. The family would pay a dime for popcorn and share it. “The wholesome nature of that sort of movie theater deal is out the window these days,” said one of the Kaspars’ children, Chris Kaspar, who initially ran the cinema for his family. “So when you come to my theater, you kind of get to step back” in time to a perhaps more innocent era.

Roger Kaspar, a biochemist, pursued investments that his son said were focused not on significant financial returns. Rather, Chris Kaspar said, they were about returns “on the goodwill of the world.” One project Roger Kaspar was involved in was trying to acclimate quinoa to Panguitch so that local farmers might have alternatives to growing alfalfa.

Chris Kaspar was studying physics in his senior year of college, which due to the pandemic he was attending remotely, while living in Panguitch and fixing up a garage into an apartment. When his father had committed fully to purchasing the Gem, Kaspar volunteered his services. “I mean, how can you pass up running a movie theater in a small town?” That said, he added, buying a movie house during a pandemic “is a terrible time (to do it).”

The Kaspars wanted to help strengthen the community, “and we recognize that if you put in capital investment that could go a long way,” Chris Kaspar said. Shortly after the Kaspars bought the Gem, Roger Kasper also acquired the Two Sunsets hotel across the street from the movie house. The Kaspars hoped that by putting money into the town they would attract tourists. Bryce Canyon National Park is just 21 miles away from Panguitch and many of the hundreds of thousands of tourists who weekly flock to the red rock canyons stay in nearby towns. By upping Panguitch’s game, with a reinvigorated cinema and hotel, the Kaspars hope more tourists “will stay there and eat at the local restaurants and spend money there.”

Chris Kaspar found in Panguitch a vibrant Latter-day Saint community with active wards and sporting events. The only thing that briefly alarmed him about small town life was whenever there was a state championship there would be a parade. “Why are there so many fire trucks on the road?” he wondered.

The Kaspars knew going in they would not make money on the Gem. His father’s instruction was to try not to lose more than $10,000 a month in those first months. “So the bar was very, very low,” Chris Kaspar said. “The economics don’t work out for only one theater, for only one screen,” he continued. “But it’s close. Basically it’s a labor of love. It’s a lovely labor but it’s a labor of love.”

They looked at the Gem in terms of what value they could add. They decided to open a Utah rock shop, along with a Mexican eatery that boasted what Chris Kaspar called five flavors of “killer tamales” brought in from Arizona. They also had exotic ice cream from rare fruits that Roger Kaspar grew, which he and Chris made together.

They had a bumpy soft-opening during COVID-19, closing briefly when Garfield County saw a surge in infection rates.

They officially opened with “Wonder Woman 1984” in Christmas 2021. The staff were Kaspar, three high school girls and occasionally one of his brothers. That opening night the cinema was packed. It was the only time, Chris Kaspar said, he remembered them selling out.

Then Hollywood shut down, “so the next three months after that we were awfully lonely at the theater,” he recalled. It was a brutal winter, with a $700 monthly gas bill to heat the cinema. A government stimulus check and an employee retention credit both helped the Gem soldier on.

After that first disastrous winter, the Kaspars decided the cinema would close each winter. Having graduated with his degree in 2021, Chris Kaspar had no plans of being a movie house manager all his life. “I should go and get on with my life,” he thought. In autumn 2022, they hired a new manager who was local. “She is the most popular person in town,” he said.

With his replacement in place, Kaspar left Panguitch to work remotely doing secondary research on the origins of life for Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo while traveling in the U.S. and South America. He planned to have his phone on for the next year so the new manager could reach out to him when she needed help.

“There’s going to be a lot of hard truths,” Chris Kaspar said. “There’s going to be a lot of popcorn gone into the trash can, as they say.” While they hired one person, it would still be a family affair. “They’ve got a bunch of kids and they’ll be involved.”

Resident ghosts

By early May the prospect of having to close the Ritz in Tooele loomed only larger. “The Ritz is the same,” Mickie Bradshaw wrote in an email. “If it’s a movie people want to see they will come.”

Most nights would be just a handful of people, typically regulars. When 51 people came to see “Dungeons and Dragons” it was a shock to the Bradshaws, who felt swept off their feet.

By the end of May, Alan Bradshaw had made up his mind. The final day would be June 29. They’d hold back on announcing the closure until later in the month. While the Bradshaws hoped for a private sale to someone who wanted to keep the Ritz’s doors open, ultimately they needed to dispose of the property. “So whenever something happens to me or both of us, it’s not going to be a problem to our kids, our grandkids,” Alan Bradshaw said.

After years of sacrifice and not taking out a paycheck, he felt he faced a stark choice. “I try to keep it running and it kills me or I stop and sell it. And maybe enjoy a couple more years, you know?”

As much as Cherie Black knew that it would hit her hard when the Ritz closed, she was already grateful for the time she was enjoying with her father. Away from work, he wasn’t the gruff taskmaster but rather enjoyed life. One day, he took Black and two employees fishing for rainbow trout in a small boat on Strawberry Reservoir. The men refused to gut the fish, so Black had to do it herself, but she relished her father’s laughter and how much he enjoyed the company.

Mickie Bradshaw wondered what she would do with her newfound freedom. Perhaps find a hobby, she thought. Out of all the things it would be hard for Mickie Bradshaw to say goodbye to — the cinema, employees, the popcorn, a few of their patrons — one thing not on her list were the ghosts. “I won’t miss them,” she wrote in an email.

The Bradshaws have a myriad of ghost stories. Alan Bradshaw and daughter Cherie Black, who was then 13, had all but closed up for the night when Bradshaw looked inside the auditorium one last time. A man sat with his arm around a woman, as if they were waiting for a movie to start.

“Who’s sitting in the theater?” he shouted out at an employee. “I thought you got everybody out.”

Black stared at the couple, then her father and when they looked back the couple were gone.

Bradshaw turned on the lights revealing an empty auditorium. He turned off the lights and called out, “Well, when you’re done doing what you’re doing make sure the lights are off when you leave.”

None of this surprised LaDawn Tracy. She became interested in the paranormal in the early 2000s after her sister invited her on a ghost hunt at Asylum 49, formerly the Tooele hospital.

In 2012, Tracy moved into the upstairs apartment in the Ritz building. She said she can sense ghosts and her sister can see and hear them. “We do have resident spirits, two ushers in No. 1,” Tracy said. She suspected they were former employees. “They liked their job so they just stayed.” Despite Mickie Bradshaw’s initial reluctance, she agreed to Tracy organizing ghost hunts for paranormal investigators in return for a little more income.

The Bradshaws accepted their spectral visitors without dismay or judgment. “It’s just part of any old building, you know,” Mickie Bradshaw said.

“They’re just people,” her husband added.

Phoenix rising

In late June, the Bradshaws pronounced the Ritz’s fate on the movie house’s website. “From our heart and soul we are excited to say great changes are up and coming. While we cherish our memories from the last 84 years, we look to the future of new memories to be made with friends and family. Last day will be June 29, 2023.”

The announcement provoked reminiscences online from those with memories of the Ritz dating back to their childhood and youth. In its last days, audiences dramatically returned. Some were curious to see what they had missed, while regulars wanted one last screening. In total, 800 patrons came to the last four days’ screenings of the final film, the adaptation of the Nintendo game, “The Super Mario Bros. Movie.” Nostalgia, it seemed, was a powerful marketing tool. One customer even tried to steal a sign from the front entrance that proclaimed 35 cent admission. Luckily, Alan Bradshaw had screwed it in tightly, so she was denied her memorabilia.

But even with the doors closed and the marquee no longer advertising that week’s screening, Alan Bradshaw vowed to still check in daily on “the old gal,” as his wife called her, and Mickie Bradshaw would pop her head in the beauty salon property they owned behind the movie house.

Mickie Bradshaw remained hopeful a white knight would appear, someone who wanted to ensure it was still a home for entertainment, the community, and yes, perhaps even the resident ghosts in Tooele’s historic downtown district.

“The Ritz has her dignity and deserves respect,” Mickie Bradshaw said. “So she’ll hang out, she’ll do her thing. She’ll show her best side for sure. She’s like the phoenix. She’ll be so excited to have people back.”