The last thing Idaho needs is for the Ammon Bundy standoff to turn into Ruby Ridge | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The similarities are inescapable.

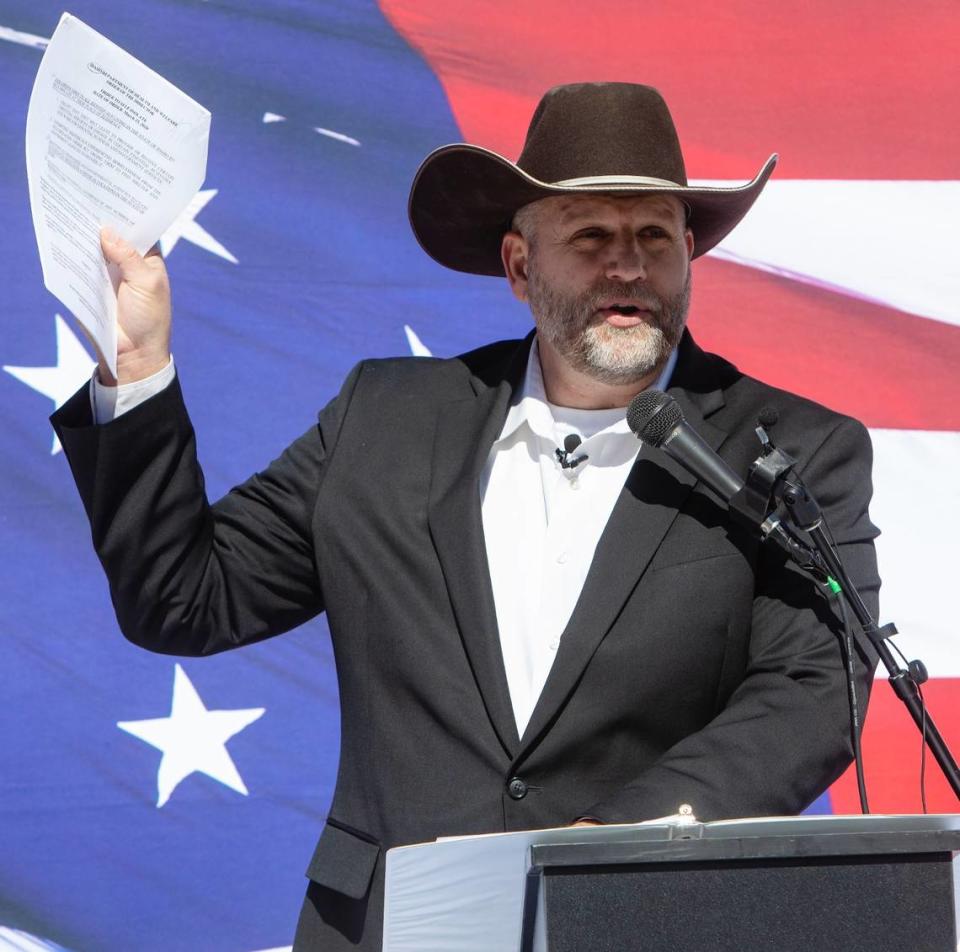

A far-right figure with a deep distrust of the federal government and a high degree of moral and religious certainty feels he’s being wrongly persecuted by the state and refuses to participate in court proceedings against him.

Ammon Bundy shouting at police officers, “Stay the hell off my property,” has eerie echoes of Randy Weaver’s response to a U.S. marshal during the Ruby Ridge standoff in 1991: “Stay off my mountain.”

The cases are different. Weaver was charged with violating federal gun laws and faced criminal charges. Bundy, no stranger to criminal charges, is embroiled in a civil matter this time, being sued by St. Luke’s for defamation.

In the Ruby Ridge case, federal authorities, including the FBI and the U.S. Marshals Service, were after Weaver. In Bundy’s case, only the Gem County Sheriff’s Office has been involved in trying to serve papers to Bundy because he has refused to respond to the lawsuit.

But the similarities and possibility of escalation are enough to raise concerns.

Bundy’s People’s Rights Network, consisting of tens of thousands of followers, this week sent out an alert that Bundy’s property in Emmett was being surrounded by law enforcement. It wasn’t. This came after Bundy had a confrontation with Gem County sheriff’s deputies who were on his property legally to serve him with court papers.

Bundy is being sued by St. Luke’s for defamation because Bundy leveled preposterous accusations against the health system in connection with a state welfare intervention on behalf of a malnourished baby who is the grandson of Bundy’s friend and co-provocateur Diego Rodriguez.

In newly published bodycam footage from the 4/6 Bundy process servicing incident, Ammon exposes his violent temper and inadvertently reveals who actually owns the property. Bundy repeatedly calls it "my property" and shouts, "I bought the place, not you!" pic.twitter.com/uX9wXmXvIC

— Devin Burghart (@dburghart) April 22, 2023

Dozens of Bundy supporters showed up at Bundy’s invitation for a “barbecue” at his property, and one supporter in attendance is recorded as saying they need to take shifts protecting Bundy from government action.

It’s unclear what the next steps are for the sheriff’s office in this case, but it’s clear Bundy is surrounding himself with his followers to deter being legally served with court papers. In an interview in December, Bundy said that he would “meet ’em on the front door with my friends and a shotgun.”

When Gem County sheriff’s deputies once served papers on an angry, aggressively yelling Bundy, they beat a hasty retreat, expressing deference and politeness. Some have criticized the deputies for that, but they played their cards right, de-escalating what could have been a more serious situation.

Law enforcement hopefully learned the lessons of Ruby Ridge, in which Weaver refused to appear in court in 1991 on a gun charge in Idaho. That led to an 11-day standoff with federal officials.

Federal agents used military tactics and surveillance to surround Weaver’s mountaintop home and were given orders to shoot on sight any armed male on the property. It led to the deaths of three people: Weaver’s wife and son, and a marshal. It also led to the wounding of another man.

As it turned out, once Weaver finally faced the gun charges, he was acquitted on the grounds of entrapment.

The justice system, of which Weaver was so suspicious, worked in his favor.

Four years after Ruby Ridge, Randy Weaver testified before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Subcommittee hearing about the standoff, how it happened and how government agencies failed.

At one point during the hearing, Weaver had an interesting exchange with then-Sen. Herb Kohl, D-Wisconsin.

“You finally did go to court, you were basically acquitted and exonerated, the laws of justice rolled on, and just in terms of what you were hauled into court for, you did all right by the American system of justice on that, didn’t you?” Kohl asked Weaver.

“Absolutely,” Weaver responded.

“You have some new feelings about our system of justice today?”

“It worked for us very well,” Weaver said.

“Do you perhaps wish that you had allowed it to work earlier?”

“Oh, yes. Oh, yeah. If I could change, believe me, I would. I’d give my life to have my son and wife back.”

“Had you allowed that system to roll on earlier – as most Americans do and are obligated to do – then justice would have been done by you. Is that a fair statement?”

“Yes, sir,” Weaver said.

Bundy believes himself to be above the law, above the rules that the rest of us follow. He believes St. Luke’s did something wrong, and it was within his authority to do something about it. Now that he’s being held to account for his actions, he is avoiding accountability.

Perhaps Bundy should listen to the words of Weaver after Weaver had time to reflect on the situation.

In his opening statement, Weaver offered what could be taken as a wise piece of advice for Ammon Bundy.

“If I had it to do over again, knowing what I know now, I would make different choices,” Weaver said. “I’d come down from the mountain for the court appearance.”

Ammon should come down from his mountain.

Statesman editorials are the unsigned opinion of the Idaho Statesman’s editorial board. Board members are opinion editor Scott McIntosh, opinion writer Bryan Clark, editor Chadd Cripe and newsroom editors Dana Oland and Jim Keyser.