After latest attack, Colorado rancher asks state to kill wolves that killed his cattle

Update: Dec. 27: The rancher's request was denied by Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

Original story

The Colorado rancher who has suffered the most livestock losses to wolves is requesting the state kill the two remaining members of the North Park pack now that it recently became legal under a federal rule.

Over the last two years, Jackson County rancher Don Gittleson has had seven cattle killed or injured by the pack — the latest confirmed by Colorado Parks and Wildlife on Wednesday, when a lone wolf badly injured a heifer.

Gittleson, who has become the poster rancher in the state's debate over wolves' impact on livestock, is sending a request to the state wildlife agency for the lethal removal of the pack's breeding male and one of its male offspring.

The option of lethal removal became available Dec. 8, when a 10(j) rule under the Endangered Species Act made it legal for wildlife officials or livestock owners to kill wolves if they are caught in the act of killing livestock or are deemed chronic depredators. Under the rule, depredation includes both injuring and killing livestock.

"The decision they make regarding my request is going to send a message to the rest of the state as to how they will handle these situations going forward," Gittleson said. "This pack has been nothing but a problem over the last two years, and these wolves should have been taken out a long time ago.''

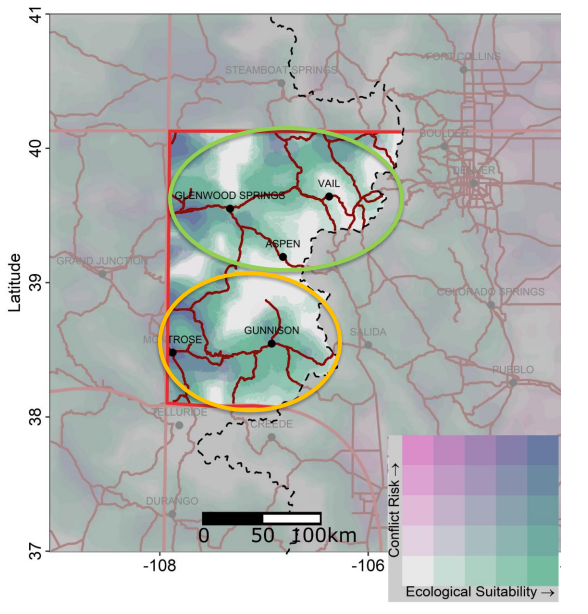

The request comes at an awkward time for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, which traveled to Oregon Sunday, Dec. 17, to begin work to capture and translocate up to 10 wolves to Colorado for its initial release of wolves in the Vail/Aspen area as part of the state's wolf reintroduction. The wildlife agency hoped to have wolves back in Colorado as early as Monday, Dec. 18.

More: Judge rules in favor of Colorado wolf reintroduction to continue

Key question in considering lethal removal of wolves: What constitutes chronic depredation?

Colorado Parks and Wildlife acknowledges the two wolves, both fitted with tracking collars, as the only verified wolves in the state. The wolves are believed to be the only remaining members of the North Park pack that once numbered eight.

The parents of that pack naturally migrated into Colorado in spring 2021 and later produced the state's first litter of pups in 80 years.

Members of the North Park pack have been confirmed by the state wildlife agency to be responsible for killing or injuring 20 livestock, including 14 cattle, three sheep and three working cattle dogs over the last two years.

Those depredations have occurred at six different ranches spread throughout Jackson County.

Other claims have been denied due to insufficient evidence.

Before the latest incident, Colorado had compensated livestock producers about $40,000 for their losses

Other states, such as Oregon and Washington, that Colorado used in part to model its own wolf recovery plan, have definitions of what constitutes chronic depredation. Those involve a certain number of depredations over a specified number of months.

Colorado chose not to define chronic depredation. Instead the state's wolf recovery plan says "CPW program managers will make the determination as to whether a situation is characterized as chronic depredation on a case-by-case basis.''

It adds the evaluation of chronic depredation will include:

Documented repeated depredation and harassment in a limited geography caused by the wolf or pack targeted.

Previously implemented practices to reduce depredation.

Likelihood that additional and continued wolf-related mortality would continue if control is or is not implemented.

Unintentional or intentional use of attractants that may be luring or baiting wolves to the location.

Gittleson said not having a definition of chronic depredation is a mistake that will cause further controversy and frustration. His losses have occurred despite the use of various nonlethal means to varying degrees of temporary success.

"I went before them during the planning process and told them they needed a chronic depredation definition,'' said Gittleson, who has been compensated for all but the most recent depredation. "They wanted flexibility, but you need a definitive line that if you cross over you can remove the wolves. If you have a definition, then there's no misunderstanding of the situation."

What wolf experts say regarding if Colorado wolves should be lethally removed

Colorado Parks and Wildlife, responding in an email to chronic depredation questions sent by the Coloradoan, said: "Discussions about whether the two collared wolves with territory that includes Jackson County would fit the definition of 'chronically depredating' have not yet occurred."

Diane Boyd is a Montana-based wolf expert who compiled a report commissioned by the National Wildlife Federation examining 40 years of extensive wolf research from across the country. The report "Lessons Learned to Inform Colorado Wolf Reintroduction and Management" was done in part to help Colorado wildlife leaders plan and manage wolf reintroduction.

She said her opinion hasn't changed since she first told the Coloradoan two years ago that members of the North Park pack should be removed after confirmed depredating on Jackson County livestock, especially given Colorado now has a 10(j) rule in effect.

"I don't like to see wild wolves killed, but this has gone on way too long," she said. "It is unacceptable ethically, morally and financially and an injustice to the wolves to allow this to continue. Wolves don't unlearn this habit. Colorado is going to have to accept the fact that some wolves will need to be removed and, as difficult as it is, if that means taking out the two remaining wolves from the pack, that’s what it means.''

Mike Phillips is the Montana-based executive director of the Turner Endangered Species Fund and has more than 40 years of experience working with wolves.

He believes Colorado needs to exhaust all properly applied nonlethal means with ranchers before turning to the removal of the wolves under the 10(j) rule.

He said if still proven a problem, the state should look at moving the wolves, not killing them.

Normally, he said, relocating wolves is not a good option because moving depredating wolves only moves the problem elsewhere and wolves normally return to the place from which they were removed. Studies have shown lethal removal of depredating wolves can temporarily reduce depredation in areas where viable wolf populations are present but is generally not considered a long-term solution.

However, Phillips said Colorado is in a unique place because it is already moving wolves into the state from Oregon as part of its reintroduction program. He said moving the two North Park pack wolves into the release area for the reintroduced wolves could help the genetic gene pool.

"Hey, sometimes you try a Hail Mary because sometimes they work," he said. "Colorado needs to be innovative and determined and not leave any stone unturned. There is no other way to justify their actions until you can say we gave it a fair shot."

Carter Niemeyer spent three decades studying gray wolf ecology, including killing wolves for the federal government, trapping wolves for reintroduction into the Northern Rockies and most recently helping ranchers with nonlethal means of dealing with depredating wolves. He is retired in Idaho and served on Colorado Parks and Wildlife's Technical Working Group for the reintroduction.

He said past experience has shown wildlife agencies are reluctant to kill or remove wolves at the beginning of when such actions are authorized under the 10(j) rule. He added removal of the two wolves might be a valid solution, but it comes with significant ramifications.

"They will be damned if they do and damned if they don't address the problem," he said. "It doesn't make a big difference in the big picture, but the symbolism of their action will create political fallout."

This article originally appeared on Fort Collins Coloradoan: Latest attack prompts Colorado rancher to request state kill wolves