Latino economy growing faster than the rest of nation's, report says

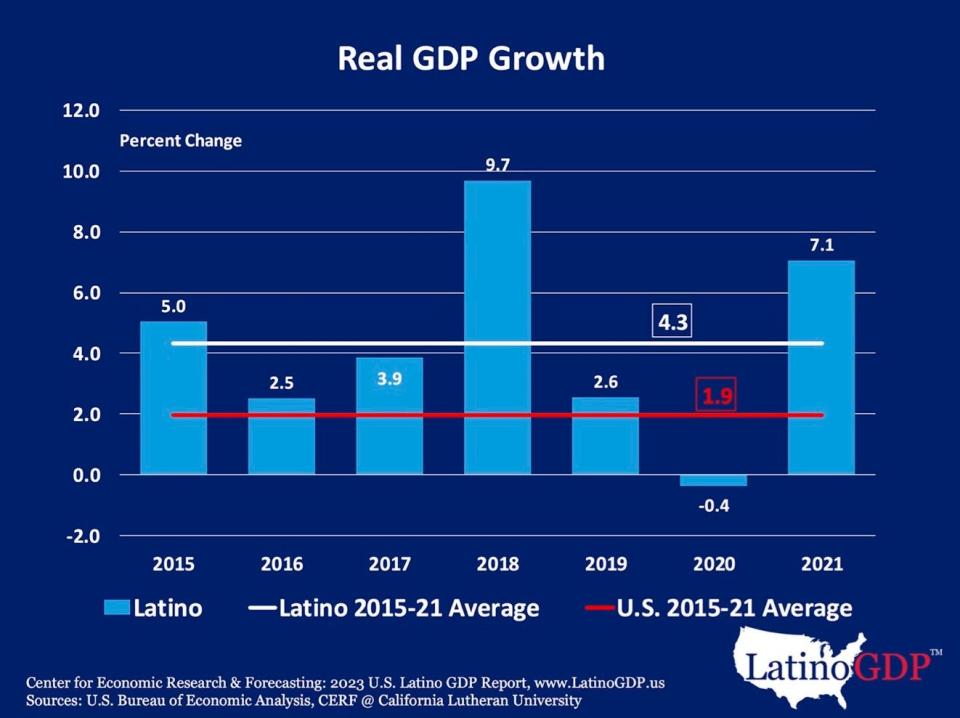

The economic impact of Latinos in the United States has been growing at more than double the rate of the overall U.S. economy, according to the latest Latino GDP report, released Wednesday by a team of researchers from California Lutheran University and UCLA.

Economists from CLU’s Center for Economic Research and Forecasting have worked with researchers from UCLA on the report since 2019. Their work measures the economic contributions of Latinos in the U.S., an impact that totaled $3.2 trillion in 2021, the last year for which data is available.

It’s the first time in the report’s history the figure has climbed above $3 trillion. If Latinos in the U.S. were a nation, its economy would be the fifth largest in the world, bigger than that of the United Kingdom, India or France.

And Latinos’ economic contributions are growing fast. From 2010 to 2021, Latino GDP grew by 3.5% per year, more than double the rate of the U.S. economy as a whole.

“The Latino economy is large, growing rapidly and very diverse,” CLU CERF director Matthew Fienup, one of the lead authors of the Latino GDP report, said during a presentation on the research at UCLA on Wednesday. “It’s more diverse than the broader U.S. economy.”

GDP stands for “gross domestic product” and represents the total value of all goods and services produced in a specific geographic region, or, in this case, by a specific group of people within a region. It’s the most common measure for the size of an economy, and GDP growth is the most common measure of the health of an economy, Fienup said.

“Increasing GDP, or economic growth, is highly correlated with things we care about deeply as a society,” he said. “It produces rising wages, higher standard of living and greater economic mobility.”

In many ways, Latinos have been holding up the U.S. economy, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020. Latinos showed 7.2% wage growth, adjusted for inflation, between 2019 and 2021, while the wages of non-Latinos shrank by 1.7%.

Latinos are more likely than other Americans to work or be seeking work; Latinos are responsible for 63% of the growth in the U.S. labor force since 2010, far more than their 19% share of the U.S. population, Fienup said.

Latinos are also, on average, younger than other Americans, and their rates of homeownership and college graduation have been growing faster than those of other Americans.

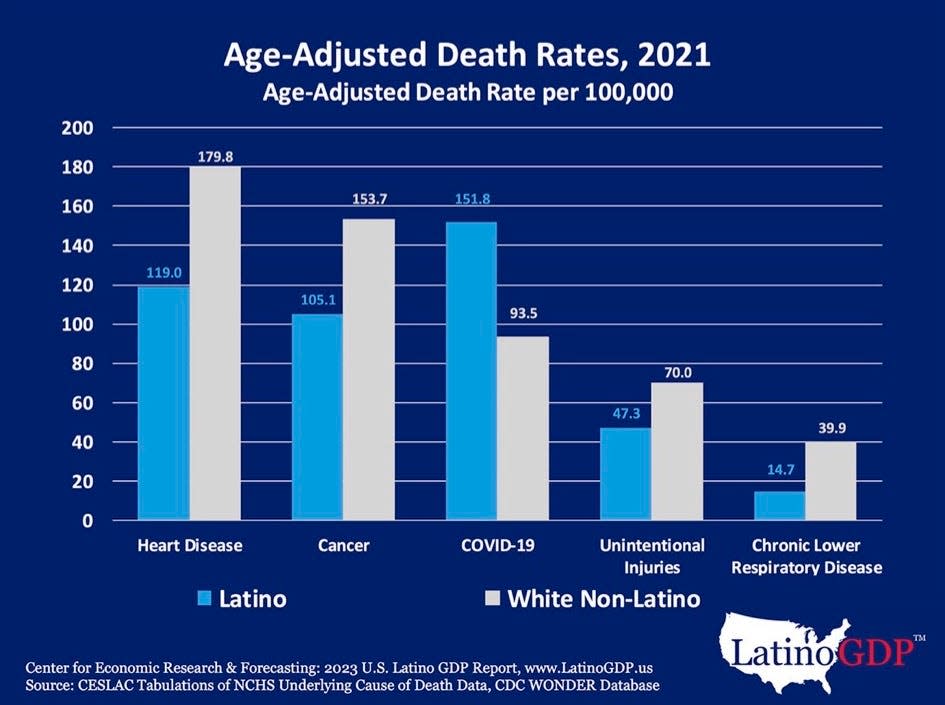

And Latinos are healthier than other Americans, though they suffered more than most from COVID-19.

Before the pandemic, Latinos had significantly lower death rates than other Americans from all the leading causes of death, including cancer and heart disease. In 2019, Latinos’ life expectancy was three years greater than that of non-Latino whites, according to the Latino GDP report.

But in 2021, COVID-19 was the third-leading cause of death in the U.S., and the age-adjusted death rate from COVID was 62% higher for Latinos than for whites. Latinos still had a higher life expectancy than whites, but the gap shrank to half a year in 2020 and a little more than a year in 2021.

“Latinos were working in front-line jobs, holding the economy up in the early days of the pandemic and catching COVID and taking it home to their families,” Fienup said.

At Wednesday’s launch event at UCLA, Fienup presented an overview of the data and then David Hayes-Bautista, a co-author of the report and the director of the Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture at the UCLA School of Medicine, gave a history lesson on Latinos in the U.S. economy.

Latinos have been active participants in the economy of what became the United States for more than 500 years, Hayes-Bautista said. Throughout the 1800s, the U.S. expanded into the western half of the continent, and the Latino economy became part of the U.S. economy.

“This is not a unique phenomenon, and it’s not recent,” Hayes-Bautista said. “This is a very old tale. It’s not that immigrants came to the U.S. economy — the U.S. economy came to Latinos and Latinos made it stronger, and we’ve been doing it for centuries.”

In recent decades, the Latino population has shifted from immigrants to their U.S.-born children and grandchildren. The new generations are more educated and are building more wealth, powering the fast-growing Latino GDP.

Antonio Villaraigosa, who in 2005 became the first Latino mayor of Los Angeles in more than 130 years, is an example of that shift. Villaraigosa sat on a panel that discussed the Latino GDP report at UCLA on Wednesday, and he said the picture painted by the data is “counterintuitive to what most people think we are,” which is still an immigrant-dominated population.

Education is the key to upward mobility, Villaraigosa said, just as it was when he was growing up.

“All four of us went to college in the early 1970s, and we did it because my mother said to us at a very young age that education was something they couldn’t take from us,” he said.

Tony Biasotti is an investigative and watchdog reporter for the Ventura County Star. Reach him at tbiasotti@vcstar.com. This story was made possible by a grant from the Ventura County Community Foundation's Fund to Support Local Journalism.

This article originally appeared on Ventura County Star: Economic impact of Latinos, Hispanics outpaces rest of US