Latino Hoosiers lead Indianapolis' population growth among racial and ethnic groups

Miriam Acevedo Davis arrived in Indianapolis in 1988 as a graduate student at Butler University.

Born in Puerto Rico but raised in New York City, she was one of few Hispanics or Latinos living in Indianapolis at the time.

“I remember being at Butler,” Acevedo Davis said, “and not meeting a lot of other Latino students.”

Her options for cultural familiarities were limited.

There were very few restaurants offering Latin American food, Acevedo Davis said, except the occasional Mexican chain like Chi-Chi’s.

Indianapolis population changes: This is how the racial makeup of Indianapolis has changed since 1970 and up to 2020 census

If she wanted a dish that tasted like home – arroz con gandules (Puerto Rican rice with pigeon peas), for instance – she’d have to make it herself; but even that was a challenge back in 1988, when most major grocery stores didn’t have what she needed, she said. She’d have to drive out to an Asian grocer on the far east side to get Café Bustelo, adobo seasoning, plantains and other ingredients she wanted.

However, since 1990, Latino Hoosiers have seen the largest percentage increase in population among any racial or ethnic group in Indianapolis; growth Acevedo Davis said she really began to notice around the same time she became president of La Plaza, Indianapolis’ oldest Latino-serving non-profit, in 2004.

There were 7,681 Latinos in Indianapolis in 1990, comprising 1% of the city’s total population, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. By 2000, the Hispanic population size nearly quadrupled to 30,636. Twenty years later, 2020 census data revealed the Hispanic population to be 13% of Indianapolis, totaling 116,844.

“Latinos, like everybody else,” Acevedo Davis said, “have come here for a variety of reasons.”

And as the population has grown, the needs of the community have evolved, she added.

Although Acevedo Davis no longer needs to travel as far to find familiar food or faces, historical disadvantages faced by the Latino community continue, which La Plaza has been working to ease since 1971, despite rising prominence among Indianapolis Latinos.

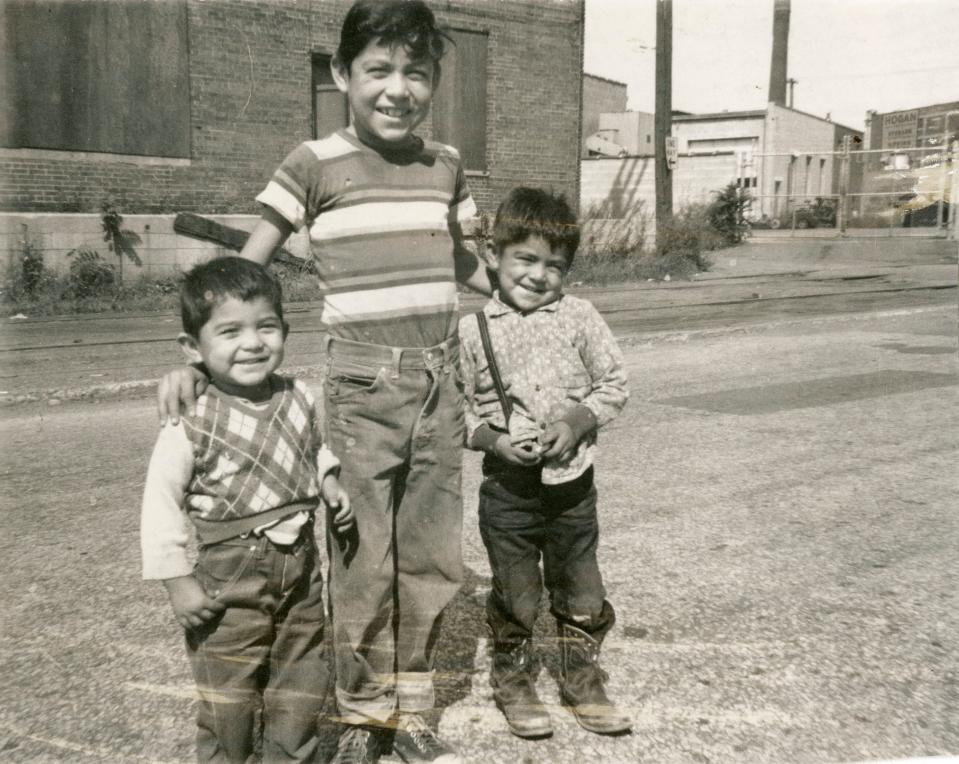

The initial migration of Hispanic Hoosiers

Nicole Martinez-LeGrand, a lifelong Hoosier, is the multicultural collections curator at Indiana Historical Society.

Like Acevedo Davis, she believes the answer to why Latinos started migrating to Indianapolis is multifaceted and complex.

“I look at immigration in three different forms,” Martinez-LeGrand said. “Push. Pull. Stick. What is pushing people out of where they are? … What is pulling them to different areas of the country? … What is that sticking factor that’s keeping people there?”

The initial pull of Latinos, mostly Mexican, toward Indiana occurred in the early 20th century, Martinez-LeGrand said, when in 1918, in response to World War I, the U.S. government authorized 30,000 Mexican nationals to work in agriculture, railroads and other defense-related employment.

'I owe them my world': Central Indiana Latinos pay tribute to their immigrant parents

Shortly after, a push of Mexican immigrants north catalyzed, she said, resulting from economic instability in Mexico that occurred after the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1920, a decade-long war.

There were over 9,000 Mexican nationals living in Indiana by the 1930s, she said.

In the 1950s, larger numbers of Hispanics migrated toward Indianapolis in pursuit of increasing job opportunities in manufacturing; and the appearance of the first major predominantly Hispanic neighborhood formed, known as the Lost Barrio, on the eastern edge of downtown (later erased by the development of Interstate 65).

“Latinos are not a new Hoosier community,” Martinez-LeGrand said. “People just think we appeared overnight.”

Economic and civil unrest occurring across Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s generated a new wave of Latino immigration into the U.S., she said, diversifying Indianapolis’ Hispanic population.

What has kept many Latinos here, enabling the present-day population percentage, is a century-long effort to build and settle a community, Martinez-LeGrand said, as well as affordability, multiple universities and international corporations recruiting diverse talent.

La Plaza adjusts to meet changing needs of the community

La Plaza was established in Indianapolis as El Centro Hispano in 1971 to address the needs of the growing Hispanic and Latino community. In 2004, the organization merged with The Hispanic Education Center, FIESTA Indianapolis, to create one nonprofit, La Plaza Inc.

For 50 years the organization has helped Hoosiers find jobs and housing; gain access to healthcare services; find emergency assistance for rent and utilities; enroll kids in school; offer domestic violence advocacy and provide mental health resources.

Still, significant disparities persist for many Latino Hoosiers. An annual 2021 report found that the median income for Latino families is 20% less than white households; Hispanic children represent 11% of the state's child population but represent 15% of youth in poverty; Latino Hoosiers represent 4% of homeowners, three-fifths what they were in 1970.

The pandemic worsened conditions. Latinos held the highest number of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population cumulatively compared to white and Black Marion County residents, in 2020. And, the undocumented community was excluded from federal stimulus checks.

In 2021, to meet changing needs of an enlarged community, La Plaza launched new developments: a microenterprise initiative to aid increasing numbers of Latino Hoosiers starting a business; and, the Latino Opportunity Center, within it, a workforce development program to help Latinos – disproportionately impacted by poverty – obtain sustainable wages.

Indianapolis events schedule: Fonseca Theatre focuses 2022 shows around theme of healing

Acevedo Davis said this year La Plaza is looking to increase their staff by 50%, after having roughly the same number of employees, 10, since 2004. They are also seeking additional space.

La Plaza served approximately 2,200 people in 2019, Acevedo Davis said, and a total of 3,500 in 2021 – more than a 60% increase.

“We need a building,” Acevedo Davis said, “to accommodate the new staff, fully launch the Latino Opportunity Center and have a meeting place for the Latino community.”

Impact of the Latino community locally

The Latino footprint within the local economy has expanded alongside population growth, despite challenges.

In a 2018 article by Indy Chamber, director of the Indiana Business Research Center, Jerry Conover, described the Latino population boom: “The metropolitan population of Hispanics and Latinos has risen by 480% in the last two decades, 16 times faster than overall population growth,” Conover said. “... it’s like adding a community the size of Carmel since the turn of the century.”

Affordable housing: Indianapolis seeks to fund affordable housing in Hillside amid gentrification fears

Organized help: For 50 years, this organization has been helping and empowering Latinos in Central Indiana

Subsequently, Conover and his team at IBRC reported a total of 4,900 Hispanic-owned firms across the nine-county metro area in 2018. Combined, they generated $1.1 billion in revenue.

Latino Hoosiers have also risen within enterprise and government ranks: Juan Gonzalez, Central Indiana president at KeyBank; Rafael Sanchez, president of private banking at Old National Bank; and former state Rep. Rebecca Kubacki.

"As our community grows," Acevedo Davis said, "we've got to make sure there are pipelines for those jobs."

Contact IndyStar reporter Brandon Drenon at 317-517-3340 or BDrenon@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter: @BrandonDrenon.

Brandon is also a Report for America corps member with the GroundTruth Project, an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to supporting the next generation of journalists in the U.S. and around the world.

Report for America, funded by both private and public donors, covers up to 50% of a reporter's salary. It’s up to IndyStar to find the other half, through local community donors, benefactors, grants or other fundraising activities.

If you would like to make a personal, tax-deductible contribution to his position, you can make a one-time donation online or a recurring monthly donation via IndyStar.com/RFA.

You can also donate by check, payable to “The GroundTruth Project.” Send it to Report for America, IndyStar, c/o The GroundTruth Project, 10 Guest Street, Boston, MA 02135. Please put IndyStar/Report for America in the check memo line.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Indianapolis Latino population face disparities, La Plaza developments