New Latino Smithsonian museum moving forward after Republicans threatened funding

If telling a balanced story about Latino contributions to the United States is a difficult task, then doing it in a single building in Washington amid disagreement in Congress over how to tell that history may be downright arduous.

That’s what the leadership of the fledgling National Museum of the American Latino is learning as they attempt to secure funding and political support for the nation’s newest Smithsonian institution, which is still years from breaking ground.

The museum, led by Founding Director Jorge Zamanillo, the former CEO of HistoryMiami, received bipartisan criticism this summer over its first effort at a public display. Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives, including Miami’s Mario Diaz-Balart, were so incensed by the exhibit that they pushed legislation forward to pull the museum’s funding.

But following a meeting late last month that eased tensions, the museum’s leaders say they are learning from the friction, incorporating feedback into their programming and working to create a venue that represents and receives support from all Hispanic Americans.

“For the first time, we’re going to have a museum, a national museum that represents all Latino communities across the U.S.,” Zamanillo, a Miami Senior High alum, told the Miami Herald. “And I think at the end of the day, most people will see that as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to support us.”

The museum, approved by a bipartisan vote of Congress in 2020, is barely in its infancy.

There is not yet a specific site for its home, which must be built along or near the National Mall. For the museum’s first effort, they’ve opened an exhibit inside the National Museum of American History called “¡Presente!: A Latino History of the United States.”

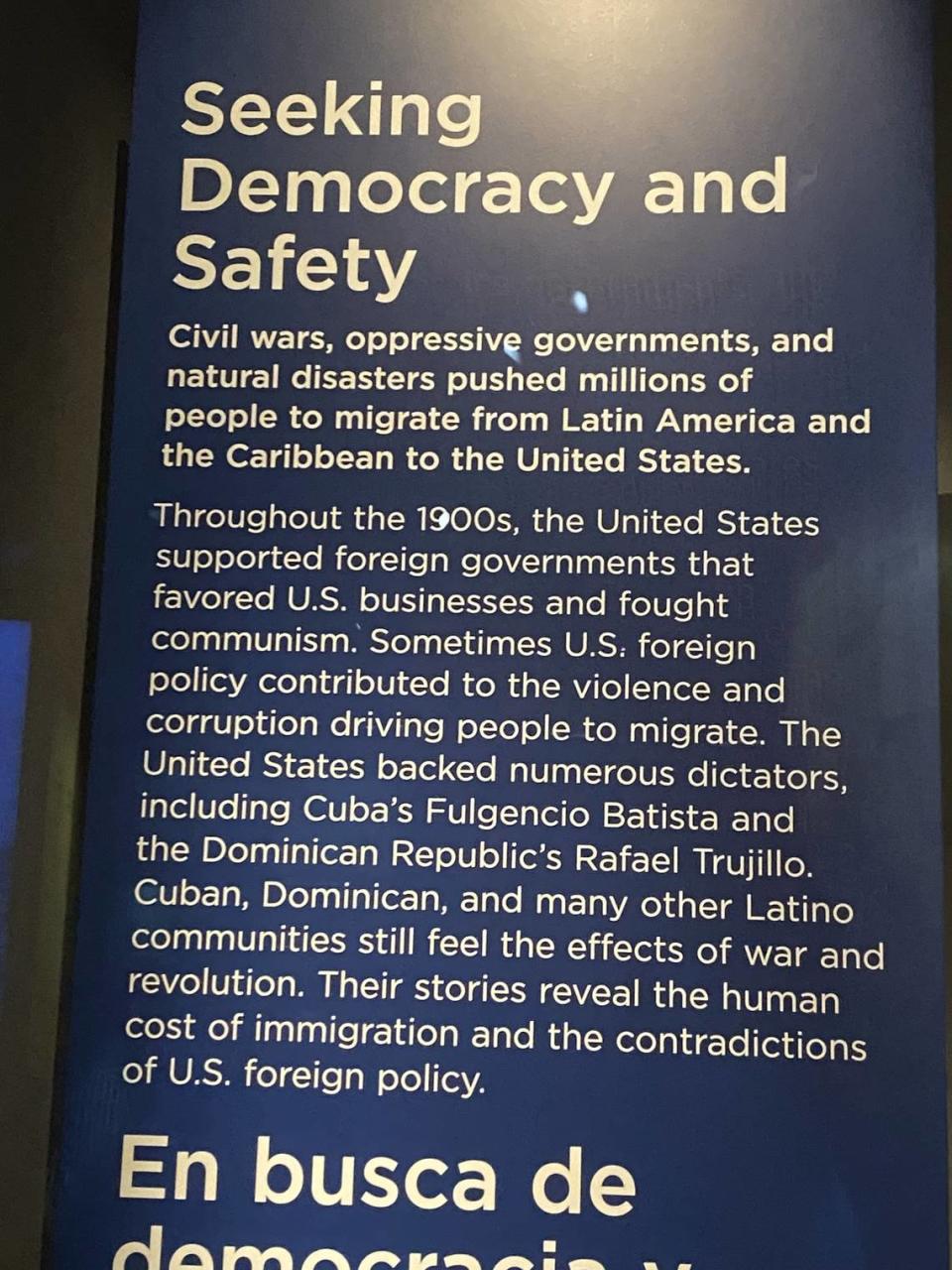

The exhibition, housed in a 4,500-square-foot gallery, was the product of years of planning and touched on 500 years of history, including colonial legacies and wars of expansion, according to a museum spokesperson and materials on its website. Interactive displays featured personal stories from Latinos about their own contributions to the country.

But about a year after it opened last summer, Republicans began to openly protest. Following visits, they said the exposition provided a one-sided picture of Latinos as “victims” and glossed over important and complex aspects of history.

Diaz-Balart, a member of the House Committee on Appropriations, described the exhibition as “patronizing” and “quasi-racist” during a subcommittee hearing last month in which lawmakers voted to block federal funding of the museum and the exhibit. He said he’d been trying to get the Smithsonian’s attention since December, and canceling the museum’s funding was the only way to force the issue.

Diaz-Balart, who is Cuban-American, protested the inclusion of a military deserter and was frustrated by a small display on Cuban balseros that in one text attributed flight from the communist, authoritarian island to economic reasons. He also objected to, he said, the inclusion of information about U.S.-backed dictatorships but not the leftist regimes largely responsible for the ongoing migration crisis.

While the frustration regarding the exhibit was bipartisan — U.S. Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, D-Weston, agreed that it was “offensive” — the debate over the depictions underscored an ongoing tug-of-war over how to tell the story of Latinos in the U.S., the struggle between left and right in the Americas and the United States’ own history of intervention in the western hemisphere.

“We are all going to be offended in one way or another by something that comes out of this museum because we are so different in so many ways,” said California Congresswoman Norma Torres, a Democrat who was born in Guatemala. “But we can’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

Moving Forward

Republicans have since dialed back their pressure. Following a meeting late last month with Smithsonian leadership, Diaz Balart announced that changes were underway and that funding would not be blocked.

“What we did is we cut the funding, and immediately [the Smithsonian] responded, and then we had a very positive meeting, and now are moving forward,” Diaz-Balart said in a subsequent interview. “I wish I didn’t have to do that in order to get their attention, but that’s what it takes sometimes with big federal bureaucracies.”

Even with the dust-up in Congress apparently settled, public condemnations of the museum’s works could be a financial problem, with the Smithsonian required to find half its funding for the new institution from outside the federal government. But the museum’s leaders say they’re continuing the work of creating programming, securing financing and building community support.

Museum trustee Alberto Ibargüen, the outgoing head of the Knight Foundation and former publisher of the Miami Herald and el Nuevo Herald, said the job is difficult, involving “a complex set of communities.”

“All of us have a Hispanic background. Not everybody looks at the world in the same way,” he said. “And there are going to continue to be honest differences of opinion.”

Zamanillo said he takes responsibility for presenting “a fair and balanced story moving forward in everything that we do” at the museum. He said part of his job will be to build and maintain political support from both Democrats and Republicans.

“I got hired here a little over a year ago. I was tasked to build a museum, to raise funds and develop that program for what you will see in any museum and it opens in 10 or 12 years. So I need to build that relationship with Congressman Diaz-Balart and others, and on both sides of the floor to make sure that they can trust me,” he said. “They can trust me to make sure that that task that I’ve been assigned to is carried out in a fair way.”

Estuardo Rodriguez, president of the Friends of the National Museum of the American Latino, created as part of the years-long effort to win authorization for the museum, said the job will not be easy.

Rodriguez, who has been working for over 19 years to make the museum a reality, said that he has heard from people across the country who also have worries that their particular perspective of Latino history will be overlooked.

“There’s always going to be a specific view of history that’s going to contrast against those who actually lived it in more modern history,” said Rodriguez. “That is the challenge for the Smithsonian. The curators need to be given: one, the benefit of the doubt, and two, the talent to do the work that is necessary to ensure that they present the most inclusive narrative possible that brings everyone together in celebration.”

McClatchyDC staff writer Gillian Brassil contributed to this report.