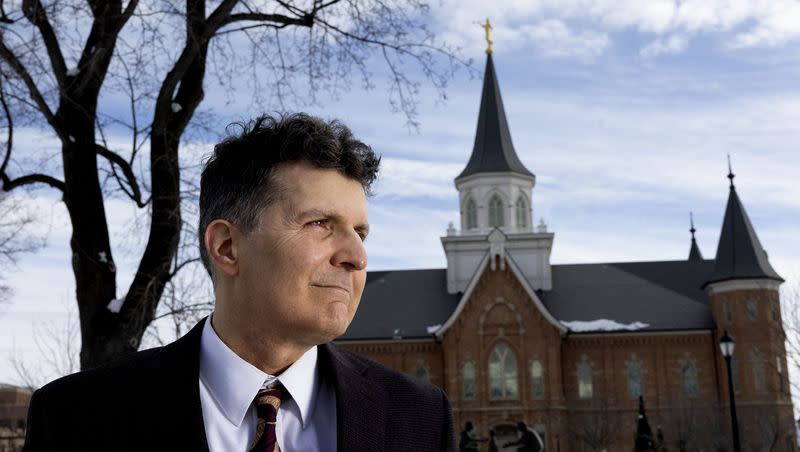

This Latter-day Saint historian left his faith. Here’s why he returned

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Don Bradley became something of a regular at the Church History Library by the time he was 18 years old. This wasn’t unusual, at least for him — he started reading Latter-day Saint thinkers like Truman Madsen and B.H. Roberts in his young teens, out of curiosity about his faith.

One day he took the bus to the library and was about to cross State Street in downtown Salt Lake City, near the headquarters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. But before he started walking he heard a warning in his mind to not cross. So, he waited and a car sped right past where he would have been walking. To him, it was a sign of God’s watchful protection.

Even though Bradley would eventually step away from religious involvement, his faith journey didn’t end there. Indeed, it was his continued study of Latter-day Saint history that eventually would influence his return. During an era when religious disaffiliation often catches headlines, Bradley’s story of reconversion is a phenomenon rarely highlighted.

Related

Coming back stories

By 2070, U.S. Christians are projected by Pew Research to compose less than half of the population. Over the last two decades, some estimate 38% of people born into Christian families have stepped back from faith. Although there’s ample attention and research focused on religious disaffiliation, there are only limited examples of research on those who actually return to faith after leaving.

But on a winter’s night in Springville, Bradley, surrounded by books, shares with me a deeper glimpse into the experience of someone who left, returned and has since worked on the Joseph Smith Papers project and published extensively on the Book of Mormon.

Unique curiosity

In his childhood, Bradley recalled his mother instilling in him deep curiosity. “I have about a dozen memories up to the age of 31⁄2. All but one have to do with curiosity.” As a child, he was naturally inclined toward science, but his devotion to faith led him to explore religious history as well.

His family moved to South Bend, Indiana, and at 15, he had an early spiritual awakening in early morning seminary, a class for Latter-day Saint teenagers. His study of sacred texts during seminary propelled his interest in all things related to the church.

When he was 17, his father took the whole family to Deseret Book. He sauntered around sections of the bookstore and still remembers the exact shelf where he saw a copy of B.H. Roberts’ “Studies of the Book of Mormon.”

This conjured new curiosities about Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon, which led Bradley to the church archives. His subsequent research extended from Ricks College to his mission in Houston and eventually to Brigham Young University. It was there he met Royal Skousen, a scholar known for Book of Mormon textual criticism who would also became a mentor.

A shaken faith

In one research project examining early sermons by Joseph Smith, Bradley was struck by the remark on “one of the grand fundamental principles” of the faith “to receive truth, let it come from where it may.” This fueled Bradley’s interest in diverse sacred texts.

When he was 29, he began wondering if faith was sufficient evidence for certain claims — concluding that if there was a “somewhat decent” naturalistic explanation, it ought to override faith-based arguments. Bradley was also impacted during this time by working on what were believed to be legitimate historical documents that turned out to be forgeries.

His faith began to collapse.

When he turned 30, Bradley said he no longer believed in God, and felt “deeply disillusioned.” He wrote a letter to his bishop explaining the decision to leave that was so harsh he thought there was no way he could ever return.

Still seeking

Even so, Bradley continued his work in church history and studied Joseph Smith more than ever. He almost gave up his research due to his personal religious frustrations, but opted to move on to graduate school at Utah State University, studying under scholar Phil Barlow.

Bradley excelled. Already a mature writer upon entering the program, it was Bradley’s “deep and rare” knowledge of primary sources that stood out to his new adviser. “His competence and vision of projects he wanted to take on was so ambitious that I had a hard time reining him in to a focused, manageable project for a master’s thesis,” Barlow remembers.

His source sleuthing didn’t go unnoticed by other scholars in the field. Brian Hales, an anesthesiologist and noted Latter-day Saint historian, needed help on a project about Joseph Smith and plural marriage with a goal to track down every source on the subject. Bradley happened to reach out when Hales was looking. “I called him Sherlock many times,” Hale said, referring to Bradley’s knack for finding sources.

Each week they would meet after Hales’ choir practice for the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square and Bradley would hand over research materials. They sometimes talked about their interpretations of the sources, which often differed from each other.

Related

Disrupting his doubts

Even though the two would disagree, Bradley couldn’t deny Hales’ commitment to examining all available sources seriously. Bradley admired Hales’ faith, reflected in his willingness to make everything public. While working together, Bradley said he also noticed Hales had something in his life that he didn’t have at the moment: a kind of inner peace.

At about this time, Bradley recounts reading an argument against the earth’s creation by a prominent atheist. Ironically, it was then Bradley learned how small the odds were for the existence of the earth and life, and he didn’t think alternative explanations were more convincing than God.

In another interview, he said it was “as much a shock to believe in God again as it had been to lose faith.” Bradley began to believe in God once again. Soon after he regained belief and became involved in the Baha’i faith.

That’s when something tragic happened in his life — his brother Charles died. Although his views of the afterlife at time were uncertain, he knew he wanted to reconnect with his brother. This punctured his former skepticism and nurtured new curiosity about the possibility of universal resurrection. As he recounted in another interview, “I had a reconversion to Christ.”

Other pivotal realizations

This left Bradley at another crossroads — which Christian church should he join? He experimented with Protestantism and dabbled in reading the Book of Mormon more and revisiting the First Vision account.

Previously, he thought Smith’s account arose from the 1830s or 1840s context in which he lived and wrote. But on closer inspection, he began to notice new confirmations he hadn’t appreciated. For instance, Smith had reported not praying aloud vocally in his early history — which aligns with Smith’s brother William implying that Joseph Smith Sr. led family prayers during this time.

Another story from Joseph Smith’s childhood stood out to Bradley — an experimental surgery where around 20 pieces of bone were chiseled and sawed out of his leg. Although without any kind of substance to numb the pain during this surgery, the young boy refused the liquor and said he would be fine as long as his father held him.

“Extraordinary people often have extraordinary childhoods,” a graduate school instructor once told Bradley. When he came across an early source about Joseph Smith Sr.’s struggle with drinking, it made sense that this young boy’s refusal of liquor may also have been a way of helping his father. “Young Joseph is trying to signal to his father, if I can handle this without alcohol, so can you.”

As Bradley would later reflect, “our questions direct our attention, and our attention determines what we perceive. So when I was pursuing the model of Joseph Smith as an opportunist, I was always asking of everything Joseph Smith said and did, what was in it for him.” It was when Bradley “broadened his questions” that he saw Smith through a different lens.

“On historical grounds alone” he had no doubt that “Joseph Smith is vastly bigger than the cynical caricature of him and that he was a sincere seeker after truth and a magnanimous soul.”

Related

Coming home again

After half a decade of not being able to figure things out, Bradley’s decision to return to his faith came together quickly.

Yet Bradley feared the letter he sent to his bishop in 2005 would mean he couldn’t return. He called his bishop and expressed his fears. The bishop said it wouldn’t be the Lord’s church if people weren’t forgiven and Bradley rejoined with fresh eyes.

This time, he said, the people in his congregation seemed more considerate, and Sunday School lessons more impactful. “I kept thinking to myself, since when have people in the church been so insightful and thoughtful in their comments?” He realized he was the one who changed.

After returning to the church, Bradley continued his research and published the book “The Lost 116 Pages: Reconstructing the Book of Mormon’s Missing Stories.” It received widespread praise by fellow scholars. Barlow said, “Don’s years of ingenious sleuthing resulted in a landmark contribution.”

Now Bradley’s working on a book about Oliver Cowdrey’s relationship to the processes of revelation and translation. He’s also working on writing more about Joseph Smith. “A huge thing in my life has been my relationship with Joseph Smith,” he said. “And as a historian, I can tell he’s religiously sincere.”

In the patterns of Joseph Smith’s behavior, he explained, “he does things that would not make the slightest bit of sense if he were not actually religiously sincere.” Bradley paused and said softly, “So he was religiously sincere” — words that could have been spoken about himself.