Lavell Lane struggled with mental health before his death. His family remembers his joy.

Anniversaries are usually something to celebrate. A marriage, a birthday or some sort of special occasion. The connotation of the word should be a happy one.

But the week of Oct. 3 is the first of many the Lane-Reese family wishes they didn’t have to commemorate. This week, they remember their son who died in Spartanburg’s county jail, a place where at least 26 people have died since 2015.

Lavell Lane, 29, was experiencing a mental health crisis when he was arrested one year ago for a “pedestrians on highways” violation.

Both his family and medical documents detail the struggles Lavell faced with his mental health dating back to 2015, including a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type.

There’s no question he needed help. The person who called 911 the evening of Oct. 2, 2022, about a near miss with a pedestrian on Chesnee Highway expressed concern someone might hit Lavell with their car, according to the audio from that night.

“I’d hate for someone to die,” they said.

The 911 operator agreed.

Instead, during the early hours of the following day, Lavell was found dead in his cell at the Spartanburg County Detention Center. A coroner’s autopsy report listed his death as neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a known, but rare, side effect of antipsychotic medications.

He received two shots of anti-psychotic medication at the jail just days before on Sept. 29.

In prior years, Lavell spent significant time at inpatient mental health facilities, often in the Upstate of South Carolina. His family described him as a “goofball” with an infectious smile while acknowledging the mental health issues he faced.

One hospital document from just days before his death reviewed by the Herald-Journal noted him as a “pleasant” individual with an unfortunate history of paranoid schizophrenia. His diagnosis at times prompted hallucinations, suicidal tendencies and erratic behavior.

Dr. Hayden Smith, professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of South Carolina, said Lavell qualified as having a “serious and persistent” mental health disorder, which consistently occurred throughout his life.

Initial jail intake and screening are critical in order to identify individual needs staff should be aware of, particularly in cases like Lavell’s, Smith said.

Six months ago, the criminal investigation into Lavell’s death was closed and absolved the sheriff’s office of criminal wrongdoing. But a civil lawsuit interrogating his death and the days preceding it calls into question the detention center’s knowledge of his mental health history and the facility’s intake procedures more broadly.

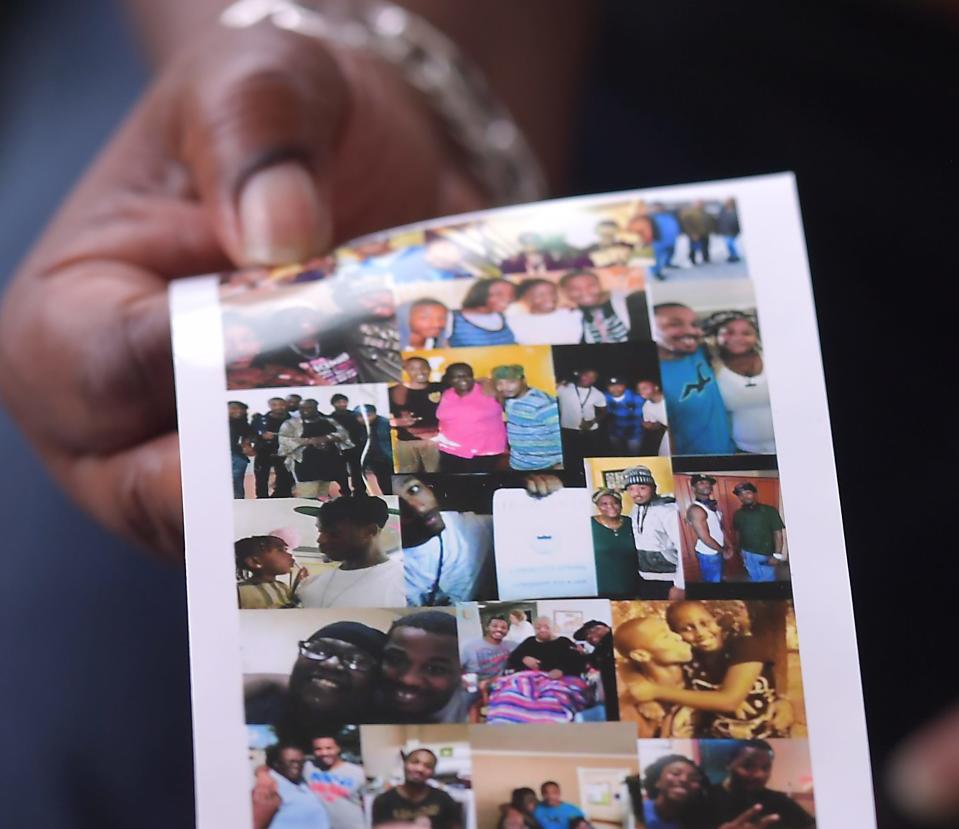

This week, the Lane-Reese family acknowledged the first anniversary of Lavell’s passing. For the past year, they’ve appeared outside the jail demanding answers about how he was treated. His medical and psychiatric past has been examined by state investigators.

But each day, all his family thinks about is how much they miss him.

A giant stuffed teddy bear, gifted by a close friend in Lavell’s memory, sits in Beverly Lane-Reese's living room. It sports a T-shirt custom printed with a poem about loss.

A short walk out the door to the garage and she encounters another item that pays homage to Lavell, specifically his running skills ― the shoes he was wearing the last time she saw him.

Beverly saw him walk out that door on Sept. 19, 2022. The shoes still sit propped against the door over a year later.

Lavell Lane remembered as joyful, despite mental health battle

Lavell Najah Lane was born at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, the seventh of what would become nine children for Beverly Lane-Reese.

Beverly described her youngest son as joyful.

“He was a happy person. You couldn't be sad around Lavell,” Beverly said. “He was upbeat. He was a jokester, a prankster.”

Andrea Reese, 21, the youngest of the Lane-Reese family, said Lavell was a dependable figure in her life who often doled out life lessons and top-tier older brother advice.

Much of his early interests revolved around sports, which his family said eventually earned him a track scholarship at a Division I college after graduating valedictorian from Acorn High School in Brooklyn.

Beverly and Andy moved down to South Carolina with Gladys Reese, Andy’s mother, and Lavell followed shortly after. Gladys and Lavell were extremely close, the family recalled.

The exact origins of Lavell’s struggles with his mental health and diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, isn’t known for certain. However, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the onset of related symptoms in males often happens in their early 20s and can be linked to a traumatic event.

Gladys died in January 2016, shortly after Lane turned 23.

“Really, that started it all,” Andrea said. “Losing somebody is not easy at all, especially someone you’ve depended on your whole life. They see you before you see yourself.”

The next year, Lavell was admitted to Patrick B. Harris Psychiatric Hospital in Anderson.

“He and my mother had a special bond,” Andy said.

Although Lavell remained outgoing, Andrea said she watched his behavior change. He initiated communication less, prompting her to reach out, and voiced feelings of being overwhelmed.

According to medical and psychiatric documents, starting in 2016 until weeks before his death, Lavell often recounted struggling with his grandmother's death. He often experienced auditory hallucinations and paranoia, the documents say.

“I’m doing good, but I just (get) depressed sometimes. It’s been hard to cope since my (grandma) died,” Lavell said, according to an intake form at Spartanburg Area Mental Health Center, an outpatient facility operated by the SC Department of Mental Health. The report is from Sept. 22, 2022, just eleven days before the coroner knocked on Beverly’s door at her Gaffney home.

Initial clinical assessment documents from a Cherokee County mental health clinic in Nov. 2016 reported a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder. A counselor reported he had no prior mental health treatment.

However, there are a few signs that predate Gladys’s passing.

The same documents show that Lavell self-reported the onset of symptoms beginning in June 2015 and expressed signs of paranoia. He also claimed he went to the roof of a building in New York as part of a suicide attempt that year. This is one instance where he claimed he heard voices, something Beverly also remembers.

Lavell also self-reported intermittent drug use in 2015 and 2016, noting that it worsened his symptoms. However, he denied using drugs in later years, and a drug screen at Spartanburg Medical Center on Sept. 27, 2022, was completely negative, including urine tests for cannabinoids, cocaine and amphetamines.

A post-mortem toxicology report collected the morning of Oct. 3 was also negative for all substances except chlorpromazine, an anti-psychotic he was prescribed, and aripiprazole, one he was administered on Sept. 29 at the jail, just days before his death.

Documents detail past mental health struggles

The criminal justice system acts as a de facto mental health system, according to Smith, who specializes in research on mental health issues in jails and prisons at USC. In prisons, he said that approximately two-thirds of female inmates and one-third of male inmates have a diagnosable mental health condition, though several factors contribute to underreporting.

“Overall, (jails and prisons) are settings that are not designed for people with mental health issues,” Smith said.

Lavell also spent time in non-carceral facilities prior to his death. He bounced around facilities in Upstate, SC, for several years, while also traveling to and from New York.

Starting in August 2018, Lavell spent roughly three years at Midway Residential Facility, a Department of Health and Environmental Control Community Residential Care Facility in Moore. Before that, he stayed at Patrick B. Harris Psychiatric Hospital in Anderson for 10 months.

On one of his returns down south, Andrea observed he underwent a noticeable weight loss.

“You could tell he wasn’t himself when he came back down here,” Andrea said.

While traveling from New York to South Carolina in July 2017, he missed his stop in Gaffney and was arrested in Beaufort County for trespassing at a hotel. While in custody, he had difficulty responding to questions and reported auditory hallucinations, according to an assessment from a Lowcountry liaison with the SC Department of Mental Health.

Lavell was admitted to Patrick B. Harris in Sept. 2017 after he reported hearing voices telling him to hurt himself. Documents from the inpatient facility described him as hyper-religious and guarded. Multiple documents testified that faith was a very important part of his life.

In August 2018, he was admitted to Midway because he was not suited for the less-structured environment of Patrick B. Harris, documents say. He spent several years at Midway until he abruptly left for New York in July 2021.

Discharge notes from Midway state that Lavell displayed a good awareness of coping skills. He was also in the beginning process of transitioning to a lower level of care with Midway staff before he left. Assessments of his daily living activities, such as maintaining physical health and communication skills, were fairly constant during his time at Midway.

He didn’t return to South Carolina for another 14 months. An investigative report from the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division states that Lane visited a hospital in New York before being sent to a behavioral health center on Sept. 19, 2022.

The report says that Lavell was provided a bus ticket from New York back to South Carolina and arrived at Midway on Sept. 20, 2022, for a final stay.

Spartanburg jail faces lawsuit, broader issues

The screening process when an individual is admitted to jail is crucial for Lavell and others who may be experiencing a mental health crisis, Smith said. The intake process should identify someone in crisis with the goal of preventing poor or dangerous outcomes.

In the first couple hours, staff should ask the individual a list of what Smith called standard questions. These should inform housing and determine how much observation an inmate needs or whether external agencies should be contacted.

Despite Lavell’s history, documents show he laid mostly still for several hours before jail staff attended to him after he appeared visibly agitated.

Attempts of self-harm or any recent visit to a physician or medical treatment are marked “no” on a Spartanburg jail Inmate Risk Assessment form for Lavell signed Oct. 2.

Generally, correctional officers must keep an eye out for warning signs, such as disorganization in thought or speech, manic behavior, and signs and symptoms of suicidal behavior, Smith said.

The lawsuit against Spartanburg County, on behalf of Lavell, alleges the jail failed to provide appropriate medical care for Lavell as required by the U.S. Constitution and the Minimum Standards for Local Detention Centers in the state.

The Minimum Standards section on medical screening states that facilities must immediately screen inmates upon admission and have the responsible medical authority approve the findings. The jail should inquire into pre-existing conditions and health problems, medications taken, behavioral observation and mental status and refer inmates to qualified medical personnel on an emergency basis.

A jail nurse said they were unable to take Lane’s vital signs “due to his behavior,” in a statement to SLED’s investigator. Documents from the detention center state that Lane attacked another inmate in the booking area and that medical staff believed he was on drugs after he allegedly reported using crack cocaine for the past ten years.

Lane’s blood sample, collected for toxicology the next morning, was negative for cocaine and all other drugs except for anti-psychotic medications.

The lawsuit claims jail staff did not investigate or learn of Lavell’s medical history to discern whether the injections given to him were medically appropriate.

The county denied those claims in the response and said staff provided detainees the correct medical care under state and federal regulations.

A report supported by USC Law School found Lane’s death was one of 23 at the Spartanburg County Detention Center between 2015 and 2022. There have been three thus far in 2023.

The report found that statewide, in-custody deaths at jails or prisons were “overwhelmingly” due to medical reasons. In Spartanburg’s jail, 14 of those 26 deaths were considered medical in nature.

Detention centers that fail to meet the minimum standards are at risk of being shut down by the state Department of Corrections.

'God doesn't make mistakes'

While litigation continues, Lavell’s family does their best to keep his memory alive.

At Beverly and Andy’s home in Gaffney, they laugh about how he loved to run, and how he loved to eat.

Andrea recalls a time when Lavell ate the candy out of her Easter basket. This laid the foundation for a running joke between them about Easter baskets for years to come.

“It hits a little different now because there’s no more of that,” Andrea said.

Less than two weeks ago, Andrea celebrated her 21st birthday. She said on her birthday last year, Lavell sent her a voicemail singing “Happy Birthday.”

“That brought me tears because I can’t hear that no more,” she said.

Beverly insists that Lavell was arrested for a “citation offense” ― walking in the middle of Chesnee Highway. She also doesn’t blame the 911 caller for their concern over the safety of someone in the road.

But what happened at the jail has left a deep impression on the family. Beverly said that once litigation has concluded, she wants to get out of South Carolina.

The memories are too painful.

During his final hours, Lavell was locked in an isolated cell after several altercations with jail staff. Smith said isolation often hurts more than it helps.

“Many of the conditions of confinement or incarceration can aggravate symptoms of mental illness,” Smith said. “They can also filter into more punitive segregation units, lockdown units.”

Close and constant observation by jail staff, especially in the first several hours of incarceration is critical, Smith said, especially if the intake process has identified an inmate as someone with a history struggling with mental health.

The coroner’s report states that Lavell spent over three hours sweating profusely and breathing heavily, while “visibly agitated and striking out at the air and walls.”

Andrea and another sister, Roxann, watched 20 minutes of footage of Lavell’s final hours in the jail. Andy and Beverly declined to view any of it.

Although she still grieves losing him, Beverly hopes her son’s death is a reminder that different people with unique needs are filtering through the penal system.

She also believes God doesn’t make mistakes.

“Lavell's death might save somebody coming behind him, somebody with mental illness. That's my purpose, is to make it known that you have to treat people accordingly," she said.

Chalmers Rogland covers public safety for the Spartanburg Herald-Journal and USA Today Network. Reach him via email at crogland@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Herald-Journal: Family remembers man who died at Spartanburg jail one year later