Lawns, gardens or natural landscapes: What to know about the Louisville yard debate

Driving through the heart of Shively in late winter, LeTicia Marshall glanced out the window. What she saw made her angry.

Where there once was a community garden — one she had worked on for about two years, and many of her neighbors before that — there was now just scattered dirt. The raised wooden beds were gone.

At city council's next meeting, on March 6, newly elected Shively Mayor Maria Johnson said the garden was removed by her order.

Community members were blindsided. Marshall said there was no discussion between the mayor and the garden's caretakers before it was dismantled ― only a notice of the executive decision.

Community gardens, as well as gardens grown in private yards, can be a lifeline for equitable access to fresh, nutritious food — especially in places like Shively and other areas of Jefferson County that are riddled with food deserts. More than 77,000 people in the county are food insecure, Feeding America estimated in 2021.

And native plant gardens can act as much-needed oases for biodiversity and pollinator populations ― cornerstones of ecosystems and global food production ― amid Louisville's urban sprawl.

More outdoor tips: What's a 'yarden'? How your yard can help fight food deserts and aid pollinators

Yet in some areas of Jefferson County, variance from the lawn is taboo. Even healthy, well-maintained landscapes have sparked fierce debate. Clusters of pollinator-friendly shrubs and flowers have drawn complaints for breaking from traditional suburban aesthetics.

Pushback against lawn dominance has cropped up nationally.

Officials in drought-stricken California restricted the use of water on "decorative or non-functional grass" last year. And a Maryland couple, whose yard of wildflowers was under siege by their homeowners' association, went to court, ultimately changing state law in 2021 to limit HOA control over "eco-friendly yards," the New York Times reported.

Last year, Louisville Metro Council revised local weed ordinances, permitting residents to grow a "managed natural landscape" and protecting the cultivation of native plants and vegetable gardens, with some limitations.

But other municipalities, like Shively and Prospect, haven't followed suit. Homeowners' or neighborhood associations may also dictate yard aesthetics.

Ensuing schisms have made a battleground of the lawn. At stake: equitable food access, plummeting pollinator populations, and the look of Louisville's neighborhoods.

Shively's community garden called 'a sliver of hope'

The Shively community was already reeling from local store closures before its garden was lost. The Kroger at Shively's Southland Terrace shuttered in 2016, and a Walmart between Shively and Pleasure Ridge Park closed its doors for good last year.

The garden behind the library "was a sliver of hope," Marshall said. In the last two years, hundreds of pounds of produce grown in the garden was distributed for free at the library, and some of it was delivered to seniors who couldn't get to a store or access mobile grocery delivery options, she added.

J. Andrew Goodman, who worked at the nearby library at the time and helped lead efforts at the garden, said Shively city clerk Mitzi Kasitz would occasionally email him, telling him a resident had complained and ask that he tidy up the garden.

Then, in February, the email was different. Kasitz told him the new mayor had ordered the garden be taken down, Goodman said.

"I was actually very angry," Goodman recalled, upon hearing the news of the dismantling, "...and I think also a feeling of powerlessness."

The Courier Journal requested all records of complaints about the garden in the six months leading up to its dismantling from Shively city government.

No records were provided.

"There were complaints all the time," Kasitz said on a phone call responding to the records request. But all resident complaints were given to the city verbally, she said, and none were kept as written records.

For the lazy gardener: 3 things to know about fertilizer, plant diversity and bugs

Kentucky plants: KY botanist finds and grows rare native plants. Here's where you can get them

Shanell Thompson, a Shively City Council member and self-described green thumb, was "devastated" and "shocked" when she found out the garden had been dismantled. In June, she proposed an ordinance based on what Louisville Metro passed last year, enshrining the distinction between careless overgrowth and maintained gardening in the city's code.

The council voted it down. None of Shively's other council members returned calls or emails from The Courier Journal on the subject. The mayor also did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

"We don't always have to agree," Thompson said of the mayor's decision. "But it is nice to be able to have a conversation."

'A garden is not a public nuisance'

At the other end of Jefferson County and in a completely different world from Shively, another garden has sparked controversy.

Jacquelyn Hawkins-McGrail's pride and joy sprouts from the soil around her two-story, brick colonial home in Prospect — another municipality proudly independent of Louisville Metro government, but where the median household income is four times higher than Shively's.

As Hawkins-McGrail wanders through her garden, pointing out the wealth of native plants and shrubs, bees buzz around her, gliding from flower to flower. In the colder months, when the garden is in a dormant state, it provides a feast of seeds for birds.

Last year, Prospect's code enforcement board levied a fine of $50 per day for the garden, deeming it a "nuisance interfering with the comfortable enjoyment of life and property of others," after a neighbor brought complaints.

Hawkins-McGrail has fought the fines tooth and nail, hiring a lawyer and bringing in environmental and real estate experts to testify in defense of her native plants as "ornamental, useful, or edible" in purpose — not weeds or public nuisances.

"And, as my attorney said, it's not like you're smelting iron in the backyard," Hawkins-McGrail said. "That would be a public nuisance. A garden is not a public nuisance."

Now, she's part of a committee revising Prospect's nuisance ordinances to better define managed natural landscapes.

As it stands, the revised ordinance would require at least half of every yard in Prospect to be a traditional grass lawn. She's disappointed by that language, calling it a step backward from existing codes that leave more ambiguity.

Her garden, she said, provides a buffet to pollinators, attracting bees and other species. A lawn doesn't achieve that, she said, and adding pesticides can produce harmful runoff.

A traditional grass lawn, "at its best, is a wasteland," Hawkins-McGrail said, "and at its worst, is a toxic wasteland."

Grass yards are good for recreation, and can serve as "negative space" in landscape design, bringing out the beauty in neighboring plants, said Paul Cappiello, executive director of Yew Dell Botanical Gardens in Oldham County.

Many centuries ago, in traditions originating in Europe, sprawling, carefully-manicured lawns were a status symbol. They indicated a property owner was wealthy enough to use their land for pleasure, rather than grow food on every inch.

Much later, the lawn became a hallmark of postwar American suburbia. But today, amid devastating habitat loss and with only a small fraction of U.S. land set aside for conservation, some experts argue conservation efforts will require private landowner buy-in — including letting go of lawn uniformity.

Varying rules for homeowners associations

Buried in the bylaws of Louisville's homeowners' associations, rules on yard maintenance are often vague and subjective.

Terms like "neat" and "attractive" make frequent appearances, as some communities "basically try to legislate taste and style," said Cappiello, whose residence in the Highlands neighborhood is HOA-free.

In Smoketown, Jody Dahmer's condo community had a shared outdoor space, mostly covered in grass. The condo association paid for it to be mowed regularly.

Dahmer, a community organizer involved with the local Urban Agriculture Coalition, sought to change the association's bylaws, which required association approval for any plants going in the ground.

A simple change read: "Gardening is allowed for HOA residents as long as maintained."

"Since we've changed the building bylaws, in two years, we have 30 different species of flowers and shrubs," Dahmer said. "We have reduced our mowing time from two hours to 30 minutes, and we're able to use that money on outside repairs ... everybody has been very supportive since that change."

Shawnee community garden

Harlem Dishman, 11, put it simply: The food tastes better when you pick it right off the vine yourself.

On a lot in Shawnee, Evelyn Spurley is working with kids in the neighborhood to build a youth community garden. Less than a year in the making, the soil here has already yielded squash, peppers, tomatoes and much more (the rabbits got to the strawberries first, Spurley lamented).

"It's bringing people together, and we're learning," said Ericka Seward, president of the Shawnee Neighborhood Association, in the shade of a thriving pear tree. "But then, we're in a food desert. So, when these things harvest, we can share them with the community."

Reenaja Reeves, 13, shared a story she learned while working in the garden. The story of "The Three Sisters" — corn, beans and squash — originated from indigenous agricultural practices, in which the three crops are planted together to support each other's growth.

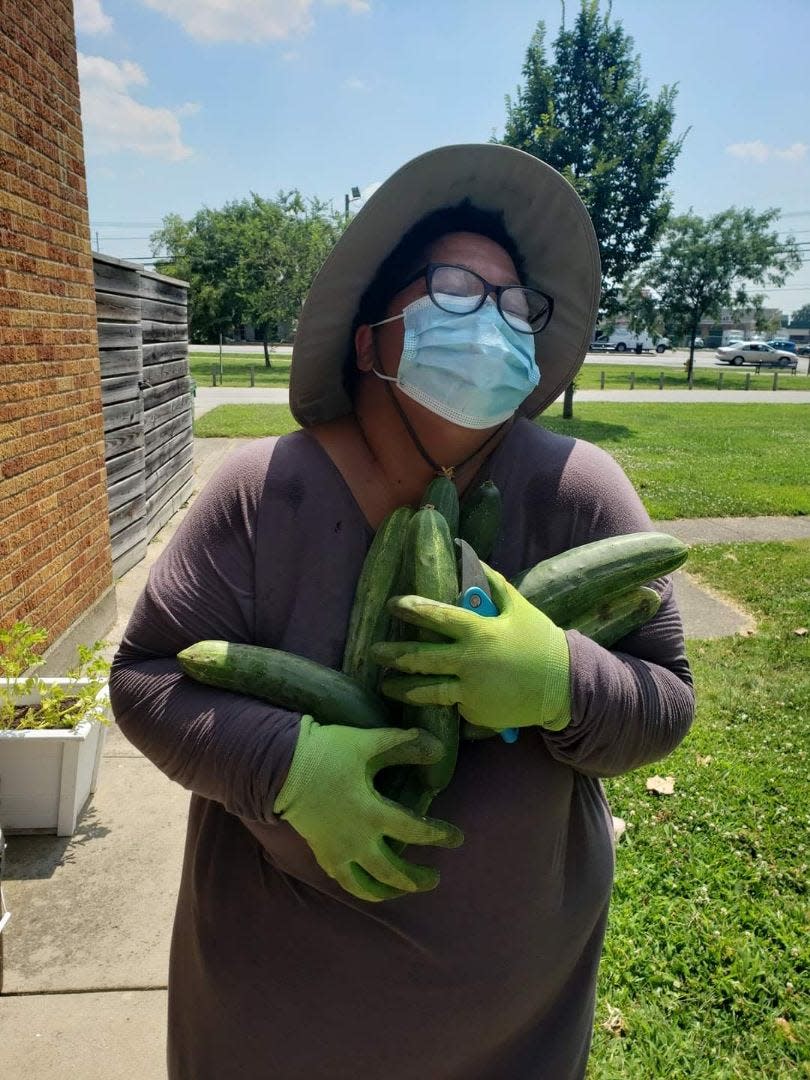

Reeves and her fellow young gardeners are each responsible for one of those three crops in the garden. On a recent summer morning, they tended to the crops, checking soil moisture under the unforgiving July sun and harvesting several plump squashes.

Like in Shively, Shawnee faces inequitable access to healthy food options. This garden helps fill that gap, but Spurley said she also hopes it teaches kids lifelong skills, responsibility and leadership.

"They're our future."

Connor Giffin is an environmental reporter for The Courier Journal and a corps member with Report for America, a national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on under-covered issues. The program funds up to half of corps members’ salaries, but requires a portion also be raised through local community fundraising. To support local environmental reporting in Kentucky, tax-deductible donations can be made at courier-journal.com/RFA.

Learn more about RFA at reportforamerica.org. Reach Connor directly at cgiffin@gannett.com or on Twitter @byconnorgiffin.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Debate over lawns vs. natural landscapes comes to Louisville area