Laws cited in Trump search warrant rarely lead to charges. In Trump's case, experts say they might

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

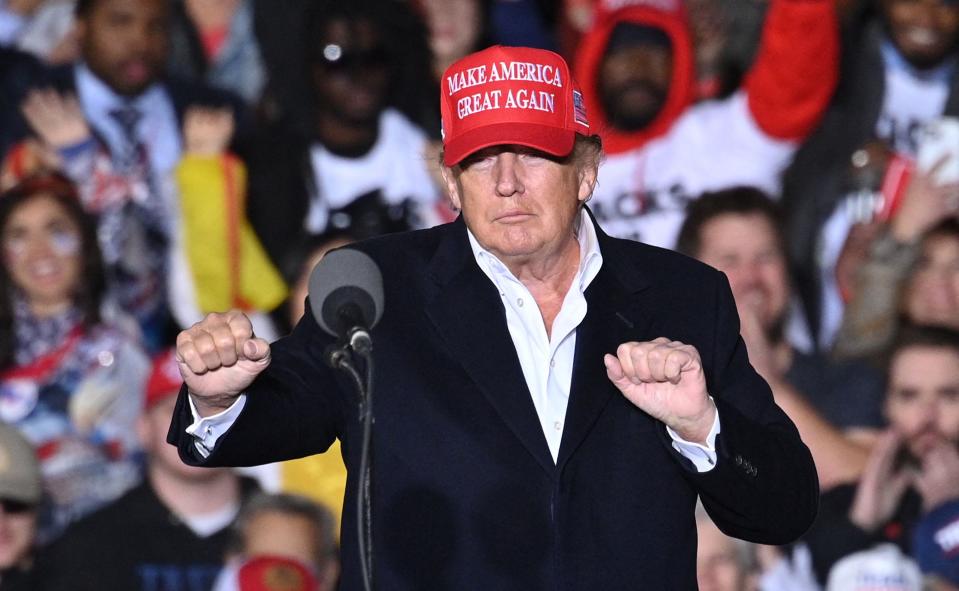

WASHINGTON – Criminal statutes cited by the Justice Department in the search of Donald Trump’s Florida estate for mishandled documents are rarely prosecuted, but legal experts say investigators may still be building a criminal case rather than simply retrieving classified records.

The FBI recovered 11 sets of “secret” and “top secret” records from Mar-a-Lago during the unprecedented search of the former president’s property. Authorities sought evidence of potential violations for mishandling defense documents, obstruction of justice and the Espionage Act.

Beyond recovering the documents, legal experts said reports of authorities interviewing Trump aides about whether documents were declassified suggest they continue to gather evidence to build a potential criminal case against Trump himself.

“I’m convinced they are building a case to determine if they can bring charges against Trump,” said Renato Mariotti, a former federal prosecutor now at Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner. “You just aren’t going to do that if your goal is to just primarily secure the documents and move on.”

Will Trump aides face charges?: Trump aides unlikely to face charges on their own in Mar-a-Lago probe, former prosecutors say

Paul Rosenzweig, a former federal prosecutor and senior counsel on the Whitewater investigation of President Bill Clinton, also said prosecutors wouldn’t pursue witnesses about Trump’s reputed standing order for declassification of documents if not to build a case.

“If they just wanted the paper back, they wouldn’t be doing that,” said Rosenzweig, who now manages Red Branch Consulting for cybersecurity. “Doing that means that they’re trying to block off defenses and lock people in."

Bradley Moss, a national-security lawyer, predicted Friday after reading the redacted affidavit that Trump would be indicted. Lawrence Tribe, a professor emeritus at Harvard Law School, said Attorney General Merrick Garland would have to prosecute Trump under the three statutes cited in the search warrant in order to uphold the rule of law.

“We have crossed the Rubicon,” Tribe said in a tweet.

Investigators weigh carelessness against negligence

The investigation of Hillary Clinton’s use of private email while serving as secretary of state was a touchstone case that legal experts cited in how prosecutors will weigh the evidence against Trump.

The FBI investigated 30,000 Clinton emails for whether her system improperly transferred or stored classified information. The probe found 110 emails contained classified information, including eight chains of messages with “top secret” information, according to then-FBI Director James Comey.

But after a review of similar cases, Comey called Clinton’s behavior “extremely careless,” but not “grossly negligent.” Comey said no criminal charges were appropriate because of a lack of willful mishandling of information, disloyalty to the United States or efforts to obstruct justice.

Daniel Richman, a former federal prosecutor who is now a professor at Columbia Law School, said the Clinton case illustrated that the nature of the documents and how they were handled will be factors in whether prosecutors pursue a case.

"It was the difference between just having documents inappropriately and making use of them," said Richman, who doesn't assume Trump will be charged.

How were other classified document cases handled?

Charges are rare under the statutes cited in the search warrant for mishandling documents.

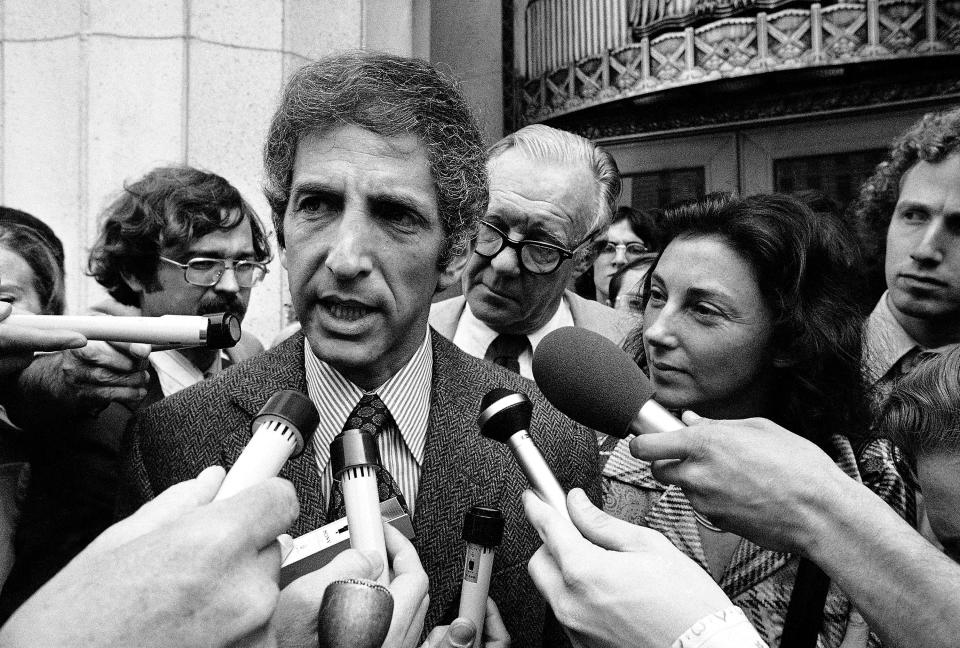

Previous cases in which such charges were pursued involve high-profile leaks about documents such as the Pentagon Papers about the Vietnam War, Wikileaks about State Department diplomatic cables or Edward Snowden’s release of information about National Security Agency surveillance.

But prosecuting those cases proved difficult.

In the Pentagon Papers case, the government dropped its charges against Defense Department analyst Daniel Ellsberg and after a mistrial featuring disclosures about undisclosed wiretaps and a government-ordered break-in at his psychiatrist’s office.

Snowden fled to Russia to avoid prosecution. The Justice Department seeks the extradition of Wikileaks leader Julian Assange from England.

When prosecuted, the cases can carry stiff penalties.

Chelsea Manning, a former Army intelligence analyst, was sentenced to 35 years in prison for providing a trove of State Department cables to Wikileaks. President Barack Obama commuted the sentence after about six years.

Jeffrey Sterling, a former CIA officer, was sentenced to 42 months in prison for revealing classified information to a New York Times reporter about a covert operation providing false nuclear blueprints to Iran.

Stephen Jin-Woo Kim, a former State Department contract analyst, was sentenced to 13 months in prison for disclosing classified information to a Fox News reporter about North Korea’s nuclear program.

More: Trump's relentless attacks on Mar-a-Lago search lack context. What he said vs. what we know.

But cases about mishandling documents have been pleaded down to lesser charges.

David Petraeus, a former Army general and CIA director, was fined $100,000 after pleading guilty to a misdemeanor for sharing classified documents with his biographer. Sandy Berger, a former national security adviser to President Bill Clinton, was fined $50,000 after pleading guilty to the same misdemeanor for sneaking classified documents out of the National Archives and destroying some copies of records.

“I would expect that any serious prosecutor will very much distinguish between the quantity of documents, the sensitive nature of documents, the use to which the documents were put,” Richman said. “What’s emerging is a story of utter contempt for government processes.”

Experts: DOJ 'too soft' with Trump

In Trump's case, the National Archives notified him in a May 10 letter that more than 100 documents comprising 700 pages were retrieved in January from Mar-a-Lago with classification markings.

"There are important national security interests in the FBI and others in the Intelligence Community getting access to these materials," acting Archivist of the United States Debra Steidel Wall said in a letter to Trump lawyer Evan Corcoran.

The letter revealed that Trump knew he had classified documents the archives sought months before the FBI search, which legal experts said could be used to illustrate criminal intent to allegedly mishandle documents.

Barbara McQuade, a former U.S. attorney and now a law professor at the University of Michigan, said the letter illustrated Trump hadn't been cooperative with federal authorities and that his claims of executive privilege to keep the documents confidential were wrong.

"If anything, they’ve been too soft," she said in a tweet.

Government demands for documents grew more urgent over time. Trump turned over the documents to the National Archives in January voluntarily, additional classified documents to federal authorities under subpoena June 3 and more documents – including 11 sets of classified records – under a search warrant Aug. 8.

Neama Rahmani, a former federal prosecutor and president of West Coast Trial Lawyers in Los Angeles, said the months of exchanges revealed criminal intent because Trump knew he held records the government sought.

“They needed to be more robust and aggressive," Rahmani said. "They really took this sort of white-glove approach with Trump."

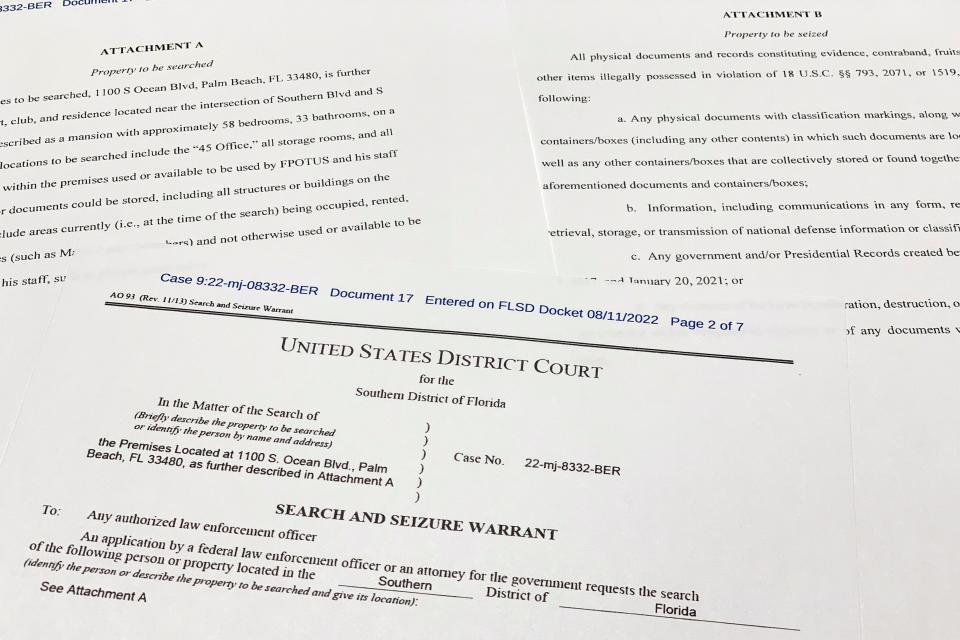

U.S. Magistrate Judge Bruce Reinhart authorized the search after the FBI notified him that the January documents included 67 marked confidential, 92 marked "secret" and 25 marked "top secret." That trove of documents included markings for clandestine human sources of intelligence, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, "NOFORN" information that can't be released to foreign governments and "ORCON" information that can't be released beyond pre-approved U.S. entities, according to the redacted FBI affidavit used to justify the search that was unsealed Friday.

Corcoran argued in a May 25 letter to Jay Bratt, the head of the counterintelligence section at the Justice Department, that Trump as president had “absolute authority to declassify documents." Because of a president’s ultimate legal authority under the Constitution, Corcoran argued his actions dealing with classified documents “are not subject to criminal sanction.”

“Beyond that, the primary criminal statute that governs the unauthorized removal and retention of classified documents or material does not apply to the president,” Corcoran wrote.

But authorities have found no documentation Trump declassified the documents. Even if he had, the statutes cited in the search warrant deal with defense and government documents, not necessarily classified records.

Andrew Weissmann, lead prosecutor for special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election and a law professor at New York University, said Trump’s claims the documents were declassified or protected under executive privilege could help prosecutors prove he knew holding the documents was wrong.

“The series of bogus defenses Trump is raising makes the criminal case against him only stronger and the discretionary factors in favor of DOJ deciding to proceed with prosecution that much weightier,” Weissmann said in a tweet.

Experts stress importance of keeping classified documents secret

While waiting for more details about the documents at stake, legal experts said the government must weigh whether prosecuting Trump would reveal more secrets.

McQuade, the former U.S. attorney, said before the release of the affidavit that the government may be reluctant to file charges against Trump for fear of “graymail,” the risk of exposing secrets during litigation. Defendants, lawyers, the judge, jury and court staff review documents used as evidence at trial, she said.

“That possibility often causes members of the intelligence community to balk at the idea of criminal prosecution,” McQuade wrote Aug. 18.

Sharon Squassoni, who specialized in nuclear arms control and security policy while working at the State Department and is now a research professor at George Washington University, said Trump’s handling of classified documents sounded alarming.

“Dumping these documents in boxes for movers to take them is just very sloppy and reveals a lack of respect for procedures and security and worse, it reveals a misguided notion of power,” Squassoni said. “You can get people killed if that information falls into the wrong hands.”

But she said we won’t know the extent of the impact until learning more about what documents were at stake. A trial could reveal more about the documents that authorities want to keep secret.

“Finding out a little more runs the risk of further damage," Squassoni said.

Richman also said pressing charges risks expose the secrets in the documents.

“If you charge an offense that requires proof about the nature of the material, you run the risk of disclosure of at least some aspect of those materials,” Richman said. “The government is wary of doing that.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Trump classified documents case: Mishandling charges rare, experts say