Lawsuit alleges Shelby County jail has 'unwritten rule' to hold inmates longer than needed

The parents of a man who was killed by another inmate inside the Shelby County Jail at 201 Poplar one year ago are suing the county over allegations that staffing shortages post a security risk. The suit also states the jail keeps defendants eligible for release in custody too long.

The lawsuit, filed in federal court in Memphis on Friday, was brought on behalf of Marcus Donald, who was strangled by another inmate last November. Earlier that day in November, Donald had entered a guilty plea and was eligible to be released, but instead of going home right away, he was held for multiple hours at the jail and placed in a new cell.

The suit names Shelby County Sheriff Floyd Bonner, Chief Jailer Kirk Fields, multiple corrections officers and Shelby County Government as defendants. Bonner and the Shelby County Sheriff's Office oversee the county's jails.

According to the lawsuit, Donald was placed in a cell with Stephen Robinson, a man previously charged with murder, and placed on lockdown at 5:30 p.m. on Nov. 17, 2022. The corrections officers that led Donald to the new cell told him he would spend the night there, the lawsuit alleges.

Before 10 p.m. on Nov. 17, Donald told a jail staff member that he should have checked out hours ago and "feared for his life locked in a cell with Robinson," according to the lawsuit.

The staff member responded with indifference, the lawsuit alleges. "'That ain't got [expletive] to do with me,'" the lawsuit contends the staff member said. "'I ain't coming to work tomorrow, no way.'"

A new shift took over at 10 p.m. that night, according to the lawsuit. When a corrections officer checked in on the pod at 10:45 p.m., the lawsuit said Donald "pleaded with her to take him out of the cell because he did not feel safe." That officer said she would try to get help, and did according to the lawsuit, but the sergeants on duty for that night "told her to ignore the escalating situation and continue making her rounds."

The lawsuit goes on to state that guards are supposed to make security rounds every 30 minutes, and to staff relief officers for each shift. However, the suit alleges those policies only existed "on paper," and that other records "suggest jail leadership stopped staffing the 2nd through 5th floor control rooms sometime prior to December 21, 2021." That, according to the lawsuit, meant there were 85 vacant guard positions to hire for.

Lawsuit outlines new details in case

According to the lawsuit, the guards that brought Donald to the new cell wrote in an incident report that they were conducting timely security rounds, but surveillance footage cited in the lawsuit allegedly indicates they were gone for almost an hour and 20 minutes — 50 minutes longer than they were meant to be away.

"The recorded video feed from 3-E pod, however, tells a more troubling story," the lawsuit said. "The truth is that no guard set foot inside 3-E for an hour and nineteen minutes, during which time Marcus Donald and Robinson began arguing, then started to fight. Robinson got control of Marcus Donald in the cell and, by his own later admission, grabbed his throat. As other inmates in 3-E tried desperately to summon the guards for help, Robinson, in his own words, slowly 'put him to sleep.'"

That signaling from nearby inmates, some of whom the lawsuit said will testify to what they saw, began at 11:12 p.m. and carried on periodically over the next hour and 10 minutes. Two inmates, according to the lawsuit, resorted to "a deliberate disciplinary infraction" by throwing things from their cells to try and get the attention of guards. Eventually, guards arrived in the pod at 12:23 a.m. — about an hour after Donald had been strangled, according to the lawsuit — and immediately took Richardson away in handcuffs.

According to this account, it was not until 12:28 a.m. — five minutes after guards arrived in the pod — that they attempted to give medical aid to Donald, and paramedics would not arrive until 12:42 a.m..

"Although SCSO policy mandates jail staff to 'assist, as much as possible, in expediting all required actions to deal with a medical emergency,' Hawkins, Wallace and other jail guards who appeared on the scene stood around Marcus Donald's helpless, strangled, unconscious body for five minutes," the lawsuit read. "They made no efforts to expedite anything."

Donald was eventually taken to Regional One Hospital, and was "nonresponsive, in cardiac arrest" when he arrived, the lawsuit said.

The lawsuit alleges that violence among inmates is part of an ongoing trend due to low staffing and not having constant supervision over inmates. Further in the suit, three incidents from 2020, 2021 and 2022 — each preceding Donald's death — are cited as "attributable to the jail's understaffing." Two resulted in deaths, and one left an inmate with "serious brain damage," according to the lawsuit.

Holding inmates eligible for release

Attorneys for the Donald family said in the suit that 201 Poplar has "an unwritten rule" that has existed for years to hold inmates who are eligible for release in jail for longer than necessary.

The Shelby County Sheriff’s Office, according to this lawsuit, says that the average time to be processed out from 201 Poplar is about two hours. The lawsuit alleges this is not true, citing a criminal court judge advising defendants who are eligible for immediate release that they should not expect to be released for another 10 or 15 hours.

"Nothing legally requires an inmate's return to the jail for processing after the disposal of his case through acquittal or dismissal, or in the event that, like Marcus Donald did on the morning docket on November 17, 2022, he entered a negotiated plea for a time-served sentence," the lawsuit reads. "Indeed, unlike Shelby County, the sheriffs of other counties in Tennessee do not mandate post-disposal custody as an unwritten rule."

It also alleges that the county, and SCSO, will say the onus was on Shelby County General Sessions Court and the Shelby County General Sessions Court Clerk for not being able to release Donald when he was eligible.

"Specifically, plaintiffs anticipate that [Chief Jailer] Kirk Fields will blame the delay on a failure to receive paper copies of Judge [Sheila] Renfroe's orders entered that day," it read. "He will claim his deputies cannot release inmates until someone from the court delivers those papers to their physical possession. That will be a lie."

According to the lawsuit, that court order is available online, and that jail personnel have "easy, immediate access" to that system.

"Surely an express refusal by the county to release inmates within a reasonable amount of time following their release eligibility deprives those persons of their liberty without just or probable cause," the suit reads. "In the face of the county’s persistent, unjustified and well-known failure to release eligible inmates from the jail within a reasonable amount of time, the county’s refusal to take action amounted to a constructive refusal to timely release inmates."

Shelby County's role in this, the lawsuit says, is complacency with the operation of the jail, even as they are informed through monthly reports called "jail report cards" that track staffing and jail populations.

"SCSO has provided the county commissioners and the Shelby County mayor with monthly 'Jail Report Cards,'" the suit reads. "These documents report the number of in-custody incidents (including inmate assaults and death), reflect (under) staffing patterns and put both the county commission and the mayor’s office on notice of the disturbing trends the jail report cards presented. Despite having notice of the jail’s chronic understaffing and correlated increase in inmate assaults and death, the mayor’s office has declined to intervene, propose any significant increase in funding for jail personnel, or request the assistance of outside law-enforcement agencies."

The lawsuit does not name a specific amount of money in damages be paid to Donald's parents, but asks for it to be "determined according to the proof," and for attorney's fees to be paid out.

When asked about the allegations in the lawsuit, SCSO said they were unable to comment on pending litigation.

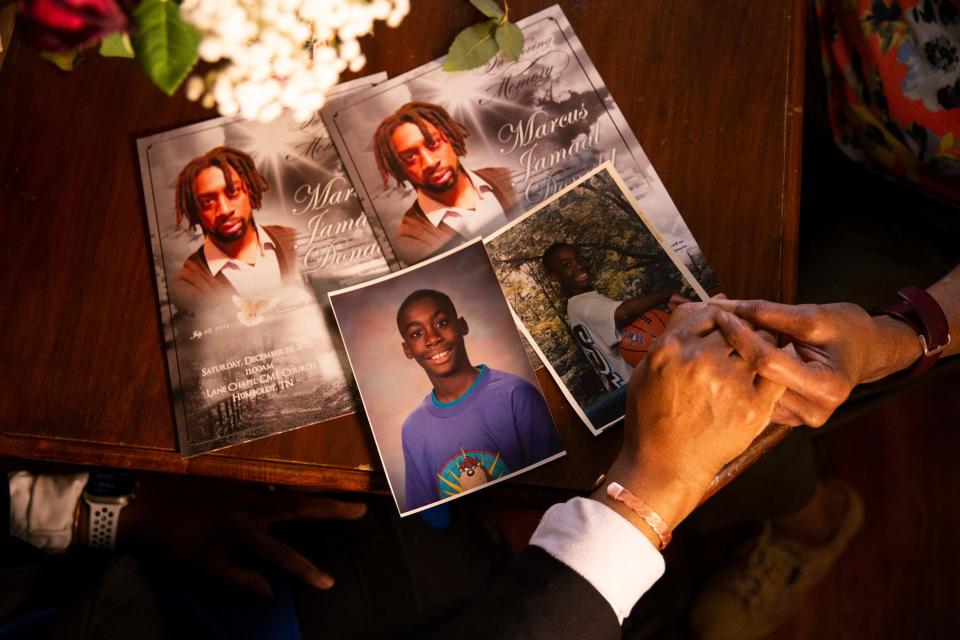

Who was Marcus Donald?

Donald was a 38-year-old Memphian who, according to his mother Marilyn Donald, was sweet and inquisitive. He played football in high school and loved his pets. His pets ranged from a dog to iguanas and hamsters.

A few years before he died, Marcus Donald converted to Judaism and fully embraced the religion, its holidays and stayed Kosher.

Although always dealing with mental health issues, according to Marilyn Donald, his mental health began to decline during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neighbors told Marilyn Donald that he was behaving oddly. Marcus Donald thought the neighbor's dogs barked too loud. He threw tomatoes at the UPS driver, and sometimes sheriff's deputies would come talk to him.

The Friday after Mother's Day 2022, a deputy called Marilyn Donald on her phone, saying they were going to take her son for a mental health evaluation. She agreed to it.

An affidavit said Marcus Donald had pointed a gun at, and then followed, a neighbor. Deputies arrested Donald and took him to 201 Poplar, where, according to records, he waited for months for an inpatient mental health stay. The pandemic pushed back court dates with illnesses. Social distancing requirements at the jail made his stay longer.

Marilyn Donald got a call at 11:15 a.m. on a Friday, 12 hours after Marcus Donald had been strangled, from a doctor at Regional One. The doctor told her that her son was at the trauma center. When Marilyn Donald arrived, she learned what had happened.

The lawsuit filed Thursday is the second civil lawsuit against SCSO and Bonner related to a death at the jail in recent months, and reflects wider community concerns over the safety of the jail.

In October, Gershun Freeman died after an altercation with corrections officers after he ran out of his cell as the officers delivered food. Nine of the officers that could be seen on footage released in March from the incident have been criminally indicted.

Two other corrections officers were indicted Tuesday for a May assault on an inmate. That inmate did not die, but sustained severe injuries, according to his attorney.

Since 2016 there have been 52 deaths at the Shelby County Jail at 201 Poplar or in transit from 201 Poplar to the hospital. Nearly 70 people have died in SCSO custody, including people shot by deputies outside of the jail and two women who died in Jail East, the county women's jail.

The mortality rate has grown over the last three years, surging past the national average. In 2022, the Shelby County Jail reported a mortality rate of 5.8 deaths per 1,000 inmates.

Lucas Finton is a criminal justice reporter with The Commercial Appeal. He can be reached at Lucas.Finton@commercialappeal.com and followed on Twitter @LucasFinton.

Katherine Burgess covers government and religion. She can be reached at katherine.burgess@commercialappeal.com or followed on Twitter @kathsburgess.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Shelby County jail lawsuit: Inmates kept longer than needed