Lawsuit: Fripp Island security guards deleted body cam footage after shooting man in 2020

The wife of a man shot and killed by a Fripp Island security guard last year has sued the property owners association and two guards, alleging the guards overstepped their authority and conspired to cover up their actions.

The lawsuit was filed Monday on behalf of Tara Steffner, whose husband Thomas “Tom” Steffner was killed by Fripp Island security on Oct. 20, 2020. The suit said that after the shooting, the guards lied to investigators about what happened, deleted their body camera footage and manipulated the crime scene to shift the blame for the shooting to the victim.

Michael Finnen, a part-time security guard for the private community and a full-time firefighter for the Lady’s Island/St. Helena Fire District, fired the shots that killed Steffner. He told investigators with the S.C. Law Enforcement Division that he was responding to a domestic disturbance and fired his weapon after he saw Steffner drawing a gun.

The 14th Circuit Solicitor’s Office declined to bring charges against Finnen after SLED’s report, though the lawsuit calls into question Finnen’s version of events.

A reporter for The Island Packet and Beaufort Gazette left messages for Finnen and Fripp Island’s security chief Wednesday. Christian Stegmaier, a Columbia lawyer who represents the Fripp Island Property Owner’s Association, which employs the security officers, said they “have no comment on pending litigation.”

On the night of the shooting, a 911 call came in to Beaufort County Sheriff’s Office dispatchers reporting a domestic disturbance at the Steffners’ home, and the Sheriff’s Office asked that Fripp Island Security respond to the scene first while deputies were en route. That relationship is not unusual, both agencies said.

But a 2008 memorandum between the Sheriff’s Office and Fripp Island, included in the lawsuit, says Fripp Island security officers are not allowed to investigate the scene or interrogate suspects, and should only interview witnesses or victims on a limited basis.

The alleged domestic disturbance turned deadly shooting highlights the unclear role of security guards in law enforcement. In many parts of Beaufort County, a private security guard will often respond to a scene of an incident before police. Twenty private communities in Beaufort County have their own security forces.

The difference in training is significant. Sheriff’s deputies require hundreds of hours of training before they start their jobs, along with yearly refreshers on deescalation. S.C. security guards are required to have only eight hours of training to get a license, and another eight hours of training to be armed.

In September, the Beaufort County School District approved a contract to hire security guards for every elementary school in the district. The Fripp Island lawsuit cited that contract as “further underscoring the need to punish these Defendants to deter similar conduct from other private security agencies in the future.”

Inconsistencies?

Fripp Island, a gated community in Beaufort County south of Hunting Island, is home to many renters in the summer.

Tom and Tara Steffner had moved there in June, four months before the shooting.

They lived next to the beach, in a home at the very end of Tarpon Boulevard, a cul de sac.

On the night of Oct. 20, 2020, a man riding a golf cart to go star-gazing called 911 and told dispatchers he heard an argument escalating at the Steffner residence, including expletives and what he thought sounded like someone being hit, according to SLED’s report.

The Beaufort County Sheriff’s Office asked Fripp Island security to respond first while deputies made their way to the island.

At 10:45 p.m., security guards Michael Finnen and Dyana Watts were notified to head to the Steffner residence.

Once there, both Finnen and Watts reported they had problems with their body-worn cameras, they told SLED investigators after the shooting.

“Finnen attempted to activate his [body cam] but could not get it turn on, and he thought the battery was dead. He later realized [the camera] was upside down and he was hitting the wrong button, thus he never activated the device,” according to the SLED report.

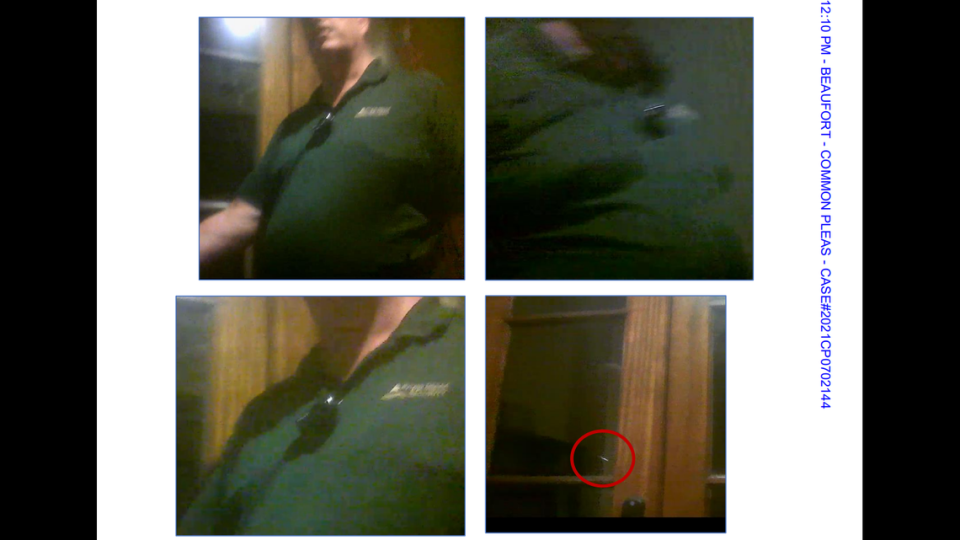

Watts’ body camera was activated prior to the shooting. In screenshots of that footage attached to the lawsuit, they appear to show Finnen’s body camera with a white LED light, indicating it was on and that it was in the correct, upright position, according to the lawsuit, which alleges Finnen lied to SLED.

Here’s what happened, according to the SLED report:

Finnen said he announced himself as Fripp Island security at the front door but got no answer. Dressed in a green polo shirt with a Fripp security logo and khaki pants, Finnen said he heard music and went to the back of the house.

The security guards climbed the stairs of the Steffners’ home to the screened-in porch where Tara and Tom Steffner were sitting at a table.

“Finnen felt they were not engaged in a fight but merely bickering, and he proceeded to walk up to them,” the SLED report said. He also said they sounded intoxicated.

Finnen told SLED that Tom Steffner walked inside the house and had a “f--k this b-lls--t” look on his face. Tara Steffner told Finnen that nothing happened and she was fine. Finnen kept asking to speak to her husband.

Steffner walked back in looking “highly angry,” Finnen told SLED, and had “his hand tucked under his shirt and wrapped around what Finnen thought was a gun.”

Finnen began demanding that Steffner show his hands.

“Hey, what-a you got in your hand there?… Drop it. I’ll f----g kill ya,” Finnen said, as heard on Watts’ body camera.

That’s when Steffner drew a gun, Finnen told investigators, and Finnen fired four shots. Two shots hit Steffner.

Watts’ account largely matched Finnen’s.

But a forensic investigation commissioned by Tara Steffner’s lawyer, Christopher Lempesis of Beaufort, found inconsistencies in Finnen and Watts’ accounts of the shooting, according to the lawsuit.

▪ Steffner was holding a broom in his right hand, which was found with a bullet-sized hole in the handle. The SLED report does not mention this.

▪ Steffner was right-handed. Finnen and Watts said he was holding a gun in his left hand.

▪ Finnen said they recovered the gun from his left hand after he hit the floor, even though he fell with enough force to sustain a concussion and bruising.

▪ One of the shots entered Steffner’s back.

▪ Both Finnen and Watts said four shots were fired, though five shots can be heard on Watts’ body camera footage. SLED’s report said five bullets were missing from Finnen’s gun.

During the shooting, Watts was on the stairwell and told SLED investigators that the dogs rushed out as a result of the noise.

Watts said the dogs knocked her over and that she fell down the stairs, causing her body camera to be removed and for the device to be shut off.

“Watts then lied to SLED and stated that her [camera] was recording but was turned off ‘accidentally’ when immediately after the shooting she fell down nearly fourteen (14) feet of steep steps onto a concrete pad,” the lawsuit alleges.

Watts was uninjured from the fall down the stairs, the lawsuit states. The Post and Courier newspaper reports Watts told SLED she was “a little sore” the next day but was not injured and did not see a doctor.

Twelve minutes of Watts’ body camera footage were missing, though the footage captured some of the shooting. She said she reactivated the device after her fall, but there wasn’t an accurate timestamp showing when it was reactivated.

After the shooting, Tara Steffner went to a friend’s house while security guards were stationed at the house.

The lawsuit alleges that while she was away, someone, at the direction of the Fripp Island Property Owners Association, “thoroughly cleaned and cleared the scene of the shooting — in an attempt to erase as much information as possible to cover up these heinous events.”

Tara Steffner told SLED her husband did not have a gun on him the entire night.

Role of security in Beaufort County

Steffner’s lawsuit seeks an unspecified amount of damages from Fripp Island POA and the security guards.

On top of suing for negligence and obstruction of justice, the lawsuit states the guards lacked authority to step onto the Fripp residence.

Previously, Maj. Bob Bromage with the Sheriff’s Office said it is routine for private security to “supplement us in the initial response” because security officers are typically close by.

In the SLED report, Fripp Island Security Chief Glenn Tabasko said his security agency does not have a memorandum of understanding with the Beaufort County Sheriff’s Office. They have a working agreement that Fripp Island security responds first, making preliminary contact, and the Sheriff’s Office arrives after to handle the actual call.

The lawsuit says that’s not true, citing a memorandum signed in 2008 between Fripp Island and Sheriff’s Office.

The MOU, attached to the lawsuit, lays out how security officers should operate with incidents in progress:

“The security officer, using established communications means, shall notify BCSO of the situation and request immediate assistance Under no circumstances should the security officer attempt any type of investigation of the crime scene or any type of interrogation of any suspects. Interviews of witnesses or victims should be strictly limited to obtaining a description of the suspect and determining the health and safety of the victim,” the MOU states.

The lawsuit states that Security Chief Tabasko and the guards should have known about the memo and, if it had lapsed, to have entered into a new one with the Sheriff’s Office.