'What I learned from my father,' the first Black secretary of the Army

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When I read that the first Black secretary of the Army, Clifford Alexander, had died at 88, I was disappointed that I knew nothing about this important civil rights hero.

His career progressed as Black people experience systemic racism throughout the United States amid national movements to advanced civil rights.

Alexander, who died last month, began his career in public service in the National Guard before becoming an assistant district attorney in New York and a foreign affairs officer under President John F. Kennedy. He was also a close adviser to President Lyndon B. Johnson, helping to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law.

Alexander did so much that a few paragraphs hardly do his legacy justice, so I spoke to his daughter, Elizabeth Alexander, president of the Mellon Foundation, about what he taught her about civil rights, love and justice.

Your father had a very prestigious education: Harvard, Yale Law. Why did he decide to devote his life to public service?

What I learned from my father of the privilege of a superb education is that you are supposed to use that for service. You are supposed to use that to empower other people.

A privileged education is not something that is given out fairly. So, you have to understand what it means to be at the table. Certainly he went to Harvard University and was president of the student body. But when he went there, the white person who was assigned to be his roommate, his parents said, "We don't want our child having a Black roommate." So, it's not like the university was 100% ready.

It was not assumed that they were welcome everywhere.

Opinion alerts: Get columns from your favorite columnists + expert analysis on top issues, delivered straight to your device through the USA TODAY app. Don't have the app? Download it for free from your app store.

After he went to Yale Law School, the big private law firms did not hire Black people. The late Leon Higginbotham has written a lot about this. On paper, he'd get all these job offers and then when he got there, the job was gone. So, for my dad, I think it was about how to turn opportunity denied into service.

There was the government and the community.

You've said your father was a feminist. Can you tell me more about that?

It began with his parents. His own mother was a fierce warrior woman, and she taught him about speaking and acting on behalf of others. His father, who was a gentler personality, showed my father the importance of service to everybody, recognizing that human beings were equal. That started in his home with his mother.

The way that he talked about and approached being secretary of the Army. When that happened, I couldn't get my head around it. He said, "It is a workplace, and a workplace where people needed to be treated fairly, and it is a workplace where women and people of color aren't treated fairly." Later on, he was a public voice in ending "don't ask, don't tell."

He had a simple belief that if we didn't make opportunity available to everyone, then as a larger community we wouldn't be as strong, able and problem solving that we could be.

What else would you want our readers to know about your father?

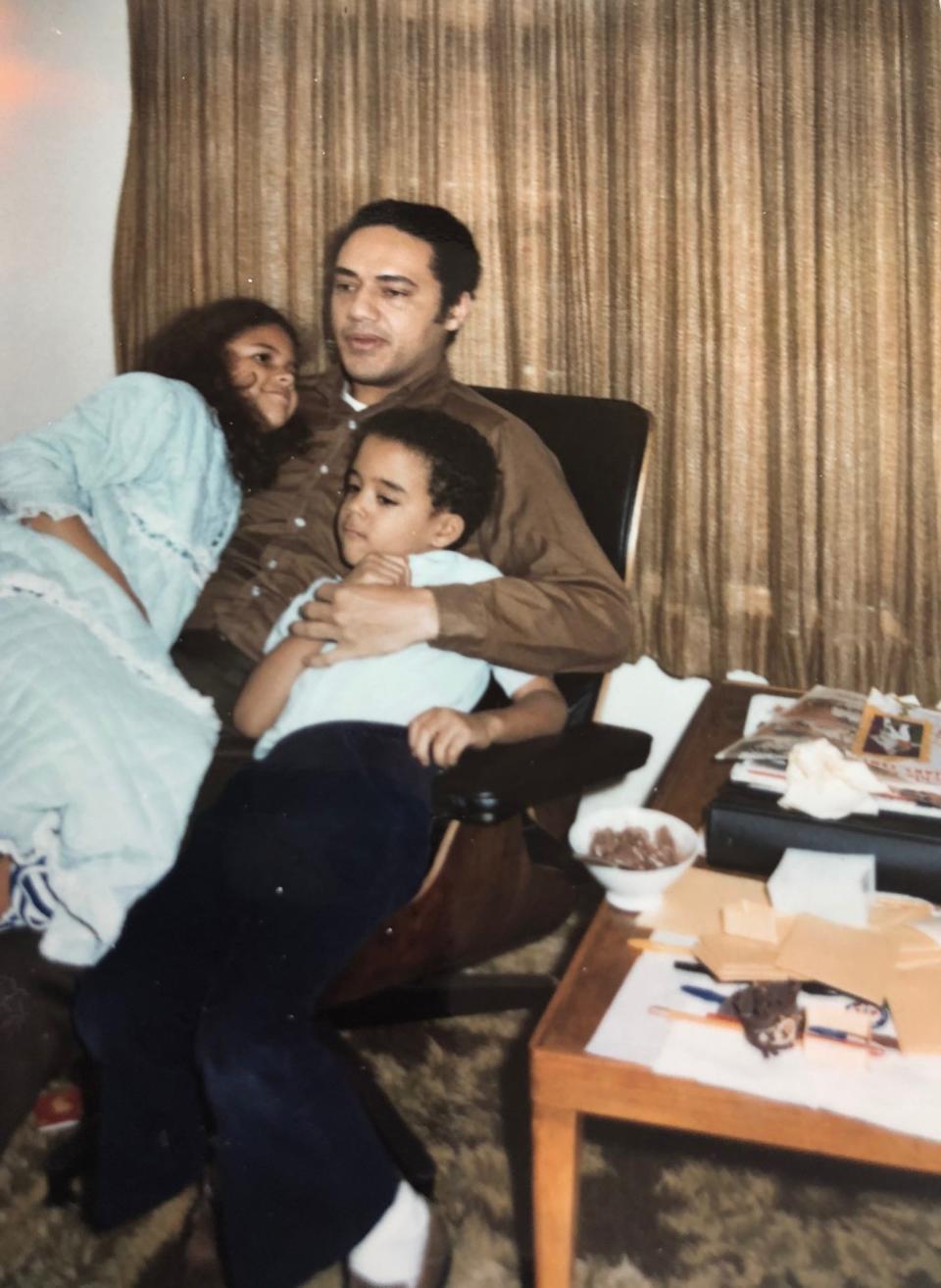

I want people to know that he was full of love. And that was a love that radiated outward. He was married to my mother for 63 years and they were absolute partners. To my brother and me, sometimes people would ask me, "Your dad had a big career and he was doing all these things. Did you see your dad?" He was so present when he was with us. He was so focused and loving. He never took his eyes off us. Everyone who encountered him encountered someone who walked in love and justice: Those two things were absolutely wedded.

Carli Pierson, a New York licensed attorney, is an opinion writer with USA TODAY, and a member of the USA TODAY Editorial Board. Follow her on Twitter: @CarliPiersonEsq

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: First Black secretary of Army dies: The life of Clifford Alexander