Lebanese revolt against their leaders in rare sign of unity

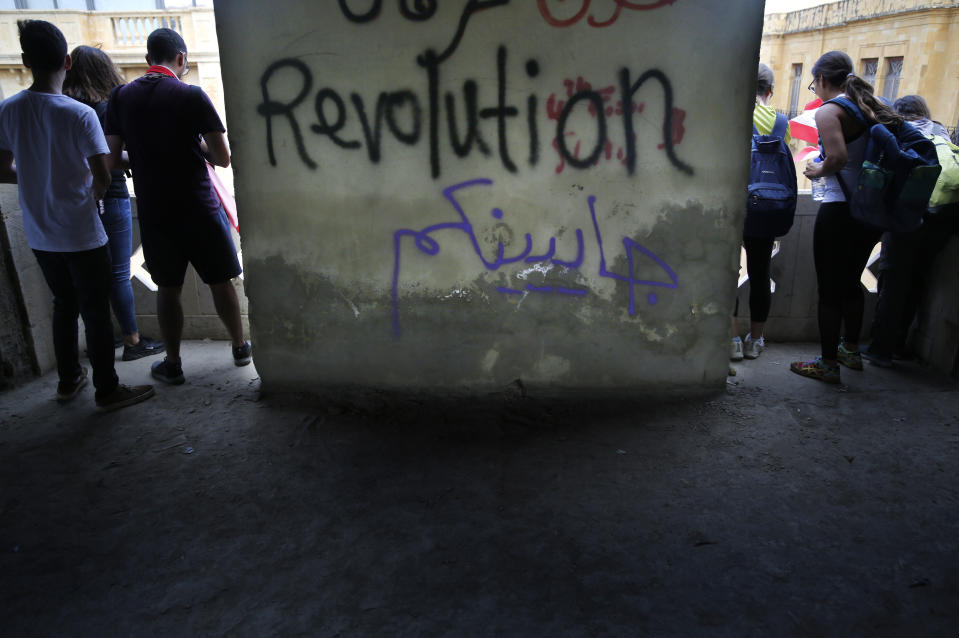

BEIRUT (AP) — Hundreds of thousands thronged public squares in the capital and across Lebanon on Sunday in the largest protests the country has seen since 2005, unifying an often divided public in revolt against traditional leaders who have ruled for three decades and brought the economy to the brink of disaster.

Ditching party flags and carrying only white and red Lebanese flags with a cedar tree in the center, they flooded streets in Beirut, the northern city of Tripoli, in eastern Baalbek as well as cities, towns and villages near the southern border with Israel and along Syria's border in the east.

In downtown Beirut, the scene was reminiscent of the days after Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was assassinated by a massive bombing in 2005, triggering a mass uprising against Syria's occupation of Lebanon after Damascus was blamed for the killing. That uprising briefly unified Lebanese from all religious sects and eventually led to the withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanon — after which society fragmented once more into bitterly divided camps.

The uprising began four days ago after the government announced new tax proposals. The announcement turned long-simmering anger into outright fury at a ruling class that has divvied up power among themselves and amassed wealth for decades but has done little to fix a crumbling economy and dilapidated infrastructure.

The target was clear: Lebanon's sectarian-based and elite-dominated political system, which has mostly kept the peace since the 1975-1990 civil war but has also spawned political paralysis and endemic corruption. In Lebanon the president is a Maronite Christian, the parliament speaker a Shiite while the prime minister is a Sunni. Cabinet and parliament seats are equally divided between Christians and Muslims.

For the first time, protesters openly took aim at powerful sectarian leaders from their own communities, turning against warlords previously regarded as untouchable and challenging them in their own strongholds. The warlords have long guaranteed loyalty by styling themselves as their sect's protectors and passing out patronage to its members.

"They (politicians) have been stealing from the people for 30 years. They stole and stole and stole and they still don't have enough," said Claire Abu Rached, protesting with her two sons, aged 10 and 8, north of Beirut.

In Tripoli, a predominantly Sunni city, some protesters chanted against and tore posters of Saad Hariri, the current prime minister and a Sunni.

Another target was Nabih Berri, the 81-year-old Shite speaker of parliament who has held the job for a quarter-century and embodies Lebanon's political status quo. On Saturday, protests in the southern city of Tyre, a stronghold of Berri's Shiite Amal movement, turned violent when his supporters attacked protesters who named him among corrupt officials and tore down his posters.

In several incidents in southern Lebanon, residents defiantly stood in front of armed Amal members, telling them they won't stop the protests even if they get shot.

Even the powerful leader of Hezbollah hasn't been spared, although he was not directly insulted during protests in the group's Shiite stronghold in southern Beirut. "All of them, and Nasrallah is one of them," they shouted.

"Thieves, thieves, thieves" the protesters in Beirut and elsewhere chanted, naming almost every senior Lebanese politician, cursing them or demanding they step down.

The atmosphere among demonstrators was euphoric and unbridled. In one often-repeated chant, a list of names of politicians was read out over a megaphone, and after each one the crowd shouted a particularly ripe obscenity. Christian leader Gebran Bassil, the foreign minister and son-in-law of President Michel Aoun, bore the brunt of that.

Rallies turned into parties with music blaring and protesters dancing, singing and chanting, "The people want to bring down the regime." In the mornings, young men and women carried blue bags and cleaned the streets of the capital, Beirut, picking up trash left behind by the previous night's protests.

"People cannot take it anymore," said Nader Fares, a protester in central Beirut who said he's unemployed. "There are no good schools, no electricity and no water."

Lebanon suffers from high unemployment, little growth and one of the highest debts ratios in the world, standing at 150% of the gross domestic product. Public services have been stagnant for years. Across the country, people rely on generators for electricity for much of the day because central power stations remain dilapidated — partly, many say, because politicians profit selling fuel for generators. The proposed new taxes that sparked the protests were part of stringent austerity measures aimed at tackling crisis, measures that critics say fall mainly on the struggling public.

Politicians are now racing to put forward a rescue plan they hope will help calm the unrest. In a speech Friday night, Hariri gave his partners in the government until Monday to come up with convincing solutions to the economic crisis.

On Sunday, the Progressive Socialist Party of Druze leader Walid Joumblatt said his two Cabinet ministers would only stay in the government if it enacts reforms. Those include no new taxes and no deductions from retirement salaries, plus an end to overspending.

On Saturday night, a Lebanese Christian leader asked his four ministers in the Cabinet to resign. Samir Geagea, who heads the right-wing Lebanese Forces Party, said he no longer believes the current national unity government can steer the country out of the economic crisis.

Hariri is expected to call for a Cabinet meeting on Monday to put forward a reform plan.

But many protesters say they don't trust any plan by the current government. They call on the 30-member Cabinet to resign and be replaced by a smaller one made up of technocrats instead of members of political factions.

"The only good thing you've done is unite us," one woman at a Beirut protest screamed. "We are all Lebanese and we all hate you."

___

Associated Press journalist Andrea Rosa contributed to this report from Beirut.