Ledger Art that gave voice to Cheyenne prisoners, on exhibit in Albany

ALBANY – It was an afternoon full of history’s color.

In the Old Jail Art Center courtyard, the Oklahoma Fancy Dancers performed in the late June heat for guests. Representing southern plains tribes like the Kiowas and the Comanches, the five members of the Connywerdy family presented a variety of traditional dances wearing brightly-colored garments.

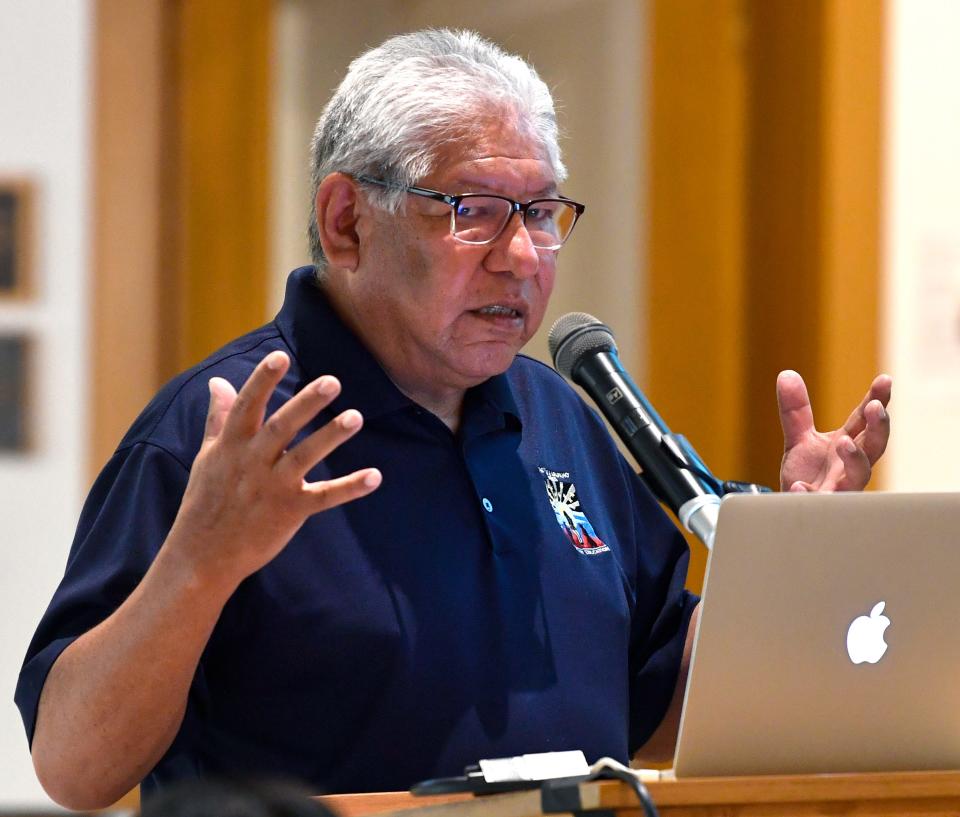

But even when they concluded their performance, demonstrations of the vibrant art of Native culture continued inside the museum as Gordon Yellowman began a lecture on the OJAC’s current exhibit, “Cheyenne Ledger Drawings: Stories of Warrior Artists,” which runs until Aug. 26.

“My traditional role for my people is I'm called a Cheyenne Chief, a member of the Council of Forty-Four, the peacemakers in the Cheyenne Nation,” he said. “I'm also a contemporary ledger artist drawing in the same style, doing contemporary narratives in my drawing which tell the story of today like when they did their drawings in 1875 to 1879.”

Visual history

Ledger art takes its name from the ledger books carried by military outfits in the 1800s which were often traded, or sometimes claimed with the spoils of battle. Their original purpose were as log books, recording a unit’s movement or cataloging expenses.

But their portability and varying sizes appealed to Native people for an entirely different reason. They made excellent drawing books.

Before the books came along, warriors would depict their accomplishments on hides made from deer, elk or buffalo. But upon the establishment of trading posts and stable communities like Bent’s Fort in Colorado, Native artists saw the utility of blank paper, especially when it came bound in book form.

“They were drawing on hides, tipi liners, tipi doors, tipi themselves,” Yellowman said.

He gestured to a standard 9-inch by 16-inch ledger book from that era, indicating that even on those tipi hides they didn’t draw much bigger than what a book like that would contain anyway.

“You would think with a big tipi, they would have bigger images,” he said. “It wasn't like that, it was the same scale of images on the tipi as you're gonna see in these books.”

Assimilation

The illustrations at the OJAC are representative of 72 Native prisoners arrested in the wake of the Red River War in 1875. Consisting of warriors from Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho and Caddo tribes, the group was sent to Fort Marion near St. Augustine, Florida for three years.

The prisoners were forced to cut their hair and dress in military uniforms in an effort to assimilate them into the society of the day.

Yet at the same time, an aspect of their culture was recognized as necessary by U.S. Army Capt. Richard Henry Pratt, whom Yellowman said brought the prisoners to Fort Marion. Pratt encouraged the men in their art.

“He wanted them to stay focused,” Yellowman said. “They had the time to produce art, he wanted them to share their uniqueness and talent that they had as artists.”

In fact, Pratt had ordered the supplies of blank ledger books and colored pencils a year in advance of the prisoners’ arrival. The captain knew there would be a market for the drawings, one from which the Natives could benefit, but also the nation if trading the works drew the artists deeper into society.

“Ladies would come in with umbrellas and white dresses, and the men would be sitting there drawing and they would sell those to the ladies,” Yellowman said. “Whatever they sold the drawing for, they would save the money to either buy material things from Florida to send home, or they would send the money to their families.”

Bartering for trade

Over time, the men would gauge the value of their drawings based upon what they could get with them. A tea kettle or coffee pot might go for four drawings, but a fancy parasol for sending back home might fetch more.

French parasols had always been a big hit. In the Bent’s Fort era in the years before the Civil War, the fancy umbrellas weren’t just for shelter from the sun.

“The umbrellas were given to the wives and the more parasols she had, the richer that warrior or hunter,” Yellowman explained. “It was a value system, ‘My husband's a good hunter, that's why I got four parasols.’”

A window to Native life

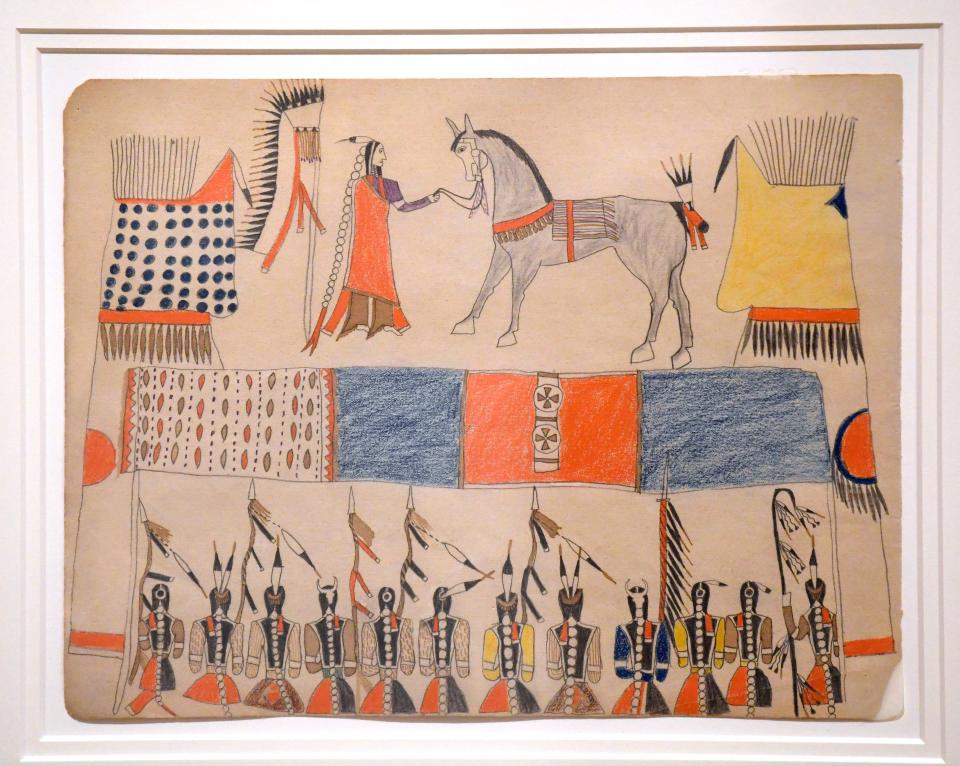

The 52 illustrations in the exhibit consist of the work of three of the Cheyenne tribesmen. The exhibit comes from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, formally known as the Cowboy Hall of Fame. The work is part of the Arthur and Shifra Silberman Collection.

Yellowman and Eric Singleton, the Curator of Ethnology at the museum, curated the exhibit with the Cummer Museum in Jacksonville, Florida where it was displayed before making its way here.

When Yellowman first saw the drawings as they were being matted for display, he was entranced by the sight of the illustrations when they were taken out of their original glass frames.

“What really struck me was I could see the actual pencil lead on the drawings, and they would glisten,” he said. “That's what really made it so powerful, to see that.”

The drawings depict the things important to a young man. Feats of courage, scenes of home, the sight of a large sailing vessel.

“Or it was courting,” Yellowman offered. “The love and compassion of courting a girl to become a wife or companion.”

“They were very romantic, very beautiful in how they documented their life stories in these drawings.”

This article originally appeared on Abilene Reporter-News: Ledger Art that gave voice to Cheyenne prisoners, on exhibit in Albany