When the Left Attacked the Capitol

In the winter of 1971, you could still find vestiges of an age of innocence in Washington. The previous decade had been one of the most unstable in the country’s history, rocked by political assassinations, racial violence and explosions at public buildings. But at the U.S. Capitol, it was still easy to stroll through without having to empty your pockets or show a driver’s license. No metal detectors or security cameras. You didn’t need to join a tour. Which is why two young people who melted into the crowd of sightseers were free to scour the building for a safe spot to set their bomb.

They were members of the Weather Underground. Since 1969, the radical left group had already bombed several police targets, banks and courthouses around the country, acts they hoped would instigate an uprising against the government. Now two of these self-described revolutionaries wandered the halls with sticks of dynamite strapped under their clothing. They slipped into an unmarked marble-lined men’s bathroom one floor below the Senate chamber. They hooked up a fuse attached to a stopwatch and stuffed the device behind a 5-foot-high wall.

Shortly before 1 a.m. on March 1, the phone call came into the Capitol switchboard. The overnight operator remembered it as a man’s voice, low and hard: “This is real. Evacuate the building immediately.”

It exploded at 1:32 a.m. No one was hurt, but damage was extensive. The blast tore the bathroom wall apart, shattering sinks into shrapnel. Shock waves blew the swinging doors off the entrance to the Senate barbershop. The doors crashed through a window and sailed into a courtyard. Along the corridor, light fixtures, plaster and tile cracked. In the Senate dining room, panes fell from a stained-glass window depicting George Washington greeting two Revolutionary War heroes, the Marquis de Lafayette and Baron von Steuben. Both Europeans lost their heads.

Shocked lawmakers condemned the attack. Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-Montana), called it an “outrageous and sacrilegious” hit on a “public shrine.” House Speaker Carl Albert (D-Oklahoma) said the bombing was “doubly sad” because it would likely lead to tighter security at the Capitol and less freedom for visitors. The Washington Post’s editorial page lamented “the easy contagion of extremism in a time of dark frustrations and deep disillusionment.”

Fifty years later, we find the nation assessing the physical and psychic wreckage left by another Capitol attack, this one at the hands of the radical right. It would be wrong to give these events equal weight on the historical scale, to simply regard them as insurrections from opposite ends of the spectrum. Dangerous and criminal as it was, the bombing amounted to a kind of guerrilla theater, a symbolic destruction of federal property to protest the disastrous military intervention in Vietnam. The Jan. 6 mob that ransacked the Capitol, causing five deaths, embodied a far more perilous delusion: that a national election was fraudulent and should be overturned with threats and violence against lawmakers. “Stop the War” versus “Stop the Steal.”

Still, the attacks do share historical context. Each arose from a cauldron of political polarization and distrust of government. They were carried out by splinter groups that had abandoned faith in American democracy and would have been pleased to see the system collapse. Both led to heightened security in Washington. Thus it may be valuable to examine the events of 1971, and what lessons those days may hold for our new era of extremism.

One big difference is that the 1971 attack was meant to oppose, not support, the sitting president, Richard Nixon. Another is that the case remains cold. While the pro-Trump mob stormed the Capitol in broad daylight, their faces captured by security cameras, their own social media feeds or witnesses with smartphones, the Weather Underground set the bomb in secret. Members were much harder to track down, since they lived together in small cells under false identities.

Since the underground group leaned on above-ground radicals for shelter, money and communications, the FBI and Justice Department decided to squeeze the Vietnam antiwar movement for information. Agents interrogated dozens of people and convened grand juries in several cities. Apparently no one cracked. Even as the feds employed increasingly aggressive and unconstitutional tactics, they had little success. Eventually, nearly all the fugitives surfaced. Yet no one ever was charged with attacking the Capitol. A half-century later, the action that the radical group considered “probably the single most important Weather bombing” remains officially unsolved.

In the wake of the Jan. 6 rampage, at least 200 people have been charged so far. Thousands more scattered around the country remain sympathetic to the rioters’ cause. While the bombing of the Capitol represented an apogee of that era’s left-wing radicalism, the lifespan of right-wing violence, powered not by small cells of self-styled guerrillas but the demagoguery of a former president, might well persist longer.

The Weather militants conceived the Capitol bomb as a curtain-raiser for the most intense season of dissent in Washington’s history. Various groups were coming to town for weeks of peaceful protests they’d named the Spring Offensive. It represented a last-ditch effort to end a war that over six years had already claimed the lives of more than 50,000 U.S. soldiers and hundreds of thousands of fighters and civilians in Southeast Asia. Picketing, marching and campaigning hadn’t stopped the killing. True, the antiwar movement had chased President Lyndon Johnson from the White House, and his successor, Nixon, had campaigned on a promise to end the war. But instead, Nixon expanded it into Cambodia and then, weeks before the Capitol bombing, into Laos.

In a communique, the Weather Underground said it had attacked “the very seat of U.S. white arrogance” to protest the Laos invasion. It wanted to prove its “solidarity” with the victims of American wars, hoping to “freak out the warmongers” and “bring a smile and a wink to the kids and people here who hate this government. To spread joy.”

Certainly, some on the left were joyful, but opinion within the antiwar movement was sharply divided about extremism. And of those planning the Spring Offensive, few could have been more distressed about the bomb than Rennie Davis.

At the age of 30, Davis, charismatic, serious and stylish—“elegant in a suede jacket,” as one columnist gushed—was one of the country’s more imaginative activists. His talent for oratory had earned him a leading role in Students for a Democratic Society, or SDS, the largest component of what came to be known as the New Left. He helped mount big demonstrations like the one in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic convention, after which the Nixon administration indicted him and seven others for conspiracy to incite a riot.

In the spring of 1971, Davis was back in Washington, where he’d grown up, to organize the finale of the Spring Offensive. Davis and his colleagues believed the movement needed to escalate tactics. He invented a slogan: “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government.” Under his plan, protesters who called themselves the Mayday Tribe would hit the streets on the morning of the first workday in May, blockading the city through civil disobedience. Participants would face arrest for obstructing traffic, but Davis and his co-organizers, especially veteran peace activist David Dellinger, promised to remain strictly nonviolent. Quakers conducted training to ensure no one would get hurt.

Now Davis worried the bomb undermined this promise of nonviolence and would bring the full force of the feds down on their heads.

His fears were justified. A few days after the explosion, two agents grabbed him as he left the Mayday headquarters at 1029 Vermont Avenue, a well-worn 11-story building a few blocks from the White House, where most peace groups had their D.C. offices. They pushed him up against a car parked in the alley and grilled him about the bombing. Davis told them what he’d been telling reporters: He was “absolutely not involved.”

One thing he didn’t mention: He’d learned about the attack in advance, and tried to stop it, as he acknowledged to me not long ago.

For Davis, the matter was personal. His younger brother, John, was a member of the Weather Underground. And he knew most of the others, because he’d worked with them in SDS, before the student group had disintegrated in 1969 as its factions battled over the proper path to social and revolutionary change.

The most militant cadres veered into guerrilla action. They saw the U.S. as a pretend democracy, structured to oppress the poor and the powerless at home and abroad. Isolated, intoxicated with self-importance, Weather took inspiration from peasant guerrilla movements in Vietnam and Latin America and from martyrs such as Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, Black Panthers who had been shot by Chicago police in their beds, an incident widely viewed as a cold-blooded execution. They felt kinship with John Brown, who led the 1859 antislavery raid at Harper’s Ferry. They taught themselves to make bombs with dynamite—“that most romantic of 19th century radical tools,” as one wrote later.

Even at the time, few leftists bought Weather’s idea that the U.S. had entered a pre-revolutionary condition that only needed some well-placed explosions and other violent confrontations with state power to spark a final uprising by the poor and working class. In the cold light of history, the group’s political and strategic analysis looks even more misguided and wacky. Yet even at its most unhinged, it promoted nothing as bizarre as the fringe theories we hear now about rigged voting machines, space lasers and international rings of satanic pedophiles.

A year before the Capitol bombing, though, Weather did take its own horrific dive down the ideological rabbit hole. One collective assembled a bomb, packed with roofing nails, intended for soldiers and their dates attending a dance at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Had they succeeded, they would have erased any question about whether they were terrorists. Instead, on the day of the dance, March 6, 1970, it was the bomb-makers who died. Somehow the device went off in their makeshift factory, in the basement of a townhouse in New York’s Greenwich Village. Three people blew themselves to bits. At least two escaped, including Cathy Wilkerson, whose father owned the house, and Kathy Boudin, daughter of a prominent liberal defense attorney.

The disaster didn’t dissuade Weather from building more bombs, but from then on, “we were very careful … to be sure we weren’t going to hurt anybody,” one said later. When Davis caught wind of the D.C. plan, he tried to head it off. He cranked up his considerable persuasive power. As a teenager he’d been famous in his Virginia hometown for talking his way out of a speeding ticket, telling a judge he’d just been racing home to finish homework. Rennie contacted his brother and others in the group. This would be no gift to the antiwar movement, he argued. Quite the contrary: A bombing now would undermine the careful preparations for the Spring Offensive.

Weather wouldn’t budge. “That was a nightmare for me,” Davis told me.

The radical group gave the action a code name: Big Top. At first, it looked like a failure.

It’s unusual that we know so much about this particular attack. Even now, ex-Weather members appear to honor an omertà about their activities. Perhaps it was youthful pride that led them to reconstruct the caper in the mid-1970s for the documentary “Underground,” directed by Emile de Antonio. They identified themselves by name, while keeping their faces obscured. Over the years, additional details have emerged from associates, friends and relatives of the bombers, who spilled anonymously to historians and authors including Susan Braudy (Family Circle: The Boudins and the Aristocracy of the Left), Ron Jacobs (The Way the Wind Blows), Bryan Burrough (Days of Rage) and Peter Collier and David Horowitz (Destructive Generation).

So we know Big Top became a project for two teams. One team posed as tourists and scouted the building. A trash can? A closet? A tunnel? Finally, they found the 5-foot wall. Full of dust, so it probably wasn’t checked regularly. On Saturday, February 27, 1971, the two members of the other team strapped the dynamite and timer to their bodies and assembled the device in the bathroom. As they lifted it into its hiding place, it didn’t sit securely. “There was a ledge where the people who did it thought there had been a shelf,” Weather member Jeff Jones explained in the documentary. “It fell several feet.” After a sickening few seconds, they let out their breath. The bomb appeared intact, still set to go at 1:30 a.m. They left the building.

The group had mailed copies of a letter to the New York Post and The Associated Press, taking responsibility. Sent by special delivery, it carried the group’s logo, a rainbow with a lightning bolt. That night, they placed their warning call. The Capitol police searched, found nothing. Zero hour came and went, and no bomb exploded. The fall must have broken the timer.

“So the organizers had a series of quick calls around the country and came up with a plan,” Jones said, “which was to take a much smaller device and go back in, and put it on top of the one that had been put there the day before. Sort of like a little starter motor.”

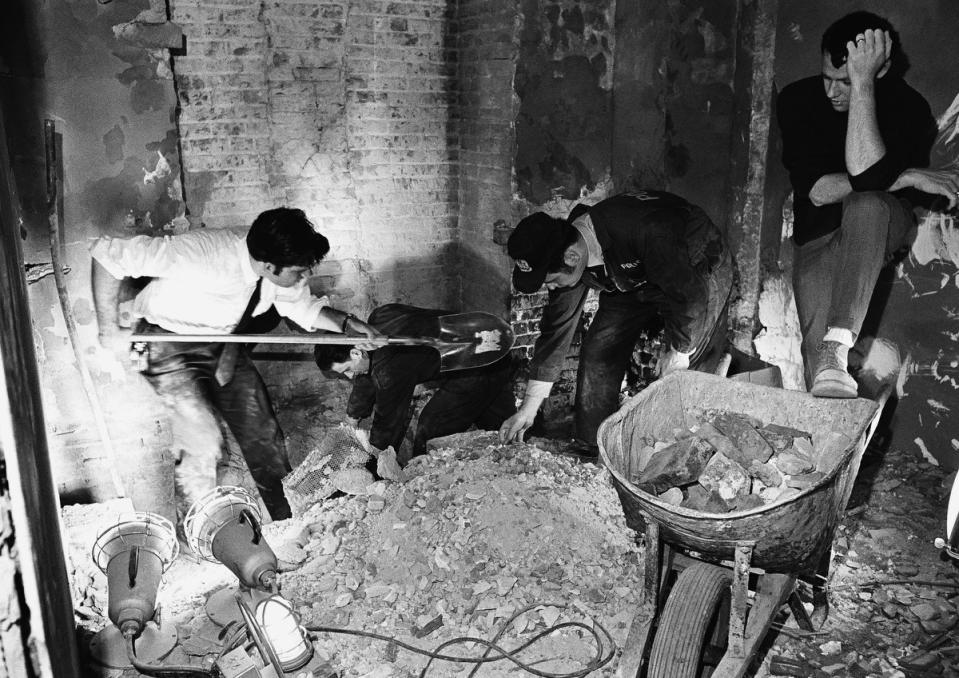

The next day, Sunday, the bombers returned, placed the new device, and called the switchboard again. U.S. Capitol Police searched as many rooms as they could in half an hour. According to an FBI report, one man checked the bathroom that held the bomb, saw nothing, and moved on. Only seven minutes later, it blew. Damage was estimated to be at least $100,000, equivalent to $650,000 today. (This week, officials put the cost of the Jan. 6 riot at $30 million.)

Neither Jones nor anyone else in the documentary named the bombers. However, at least three published accounts have identified them as two women then in their late 20s—Kathy Boudin, one of the survivors of the Greenwich Village explosion, and Bernardine Dohrn, a graduate of the University of Chicago’s law school whose looks, brains and take-no-prisoners attitude had made her a romantic icon within the left. Neither Boudin nor Dohrn has publicly admitted or denied placing the Capitol bomb. Neither responded to questions for this article.

According to Destructive Generation, it was Dohrn who called Rennie Davis in 1971. A few years ago, I visited Davis at his Colorado home as I researched my book MAYDAY 1971, about the clash between Nixon and the antiwar movement. His memories of the old days were generally quite sharp, except when it came to the Capitol bomb. He confirmed he’d been alerted about the attack in advance, but said he wasn’t told where or when it would blow. He also said he didn’t remember who called him, and he didn’t recall, if he ever knew, who actually placed the device. Davis died earlier this month from cancer, at the age of 80.

Three days after the bombing, Dohrn, already on the FBI’s most-wanted list for other crimes, nearly had been captured in the Bay Area, when she and others picked up some money wired to a Western Union office. A federal agent recognized them, but they sped away and later switched cars to elude the authorities. One of the drivers was Rennie’s brother John. His were among the fingerprints the FBI later found in a San Francisco apartment where the band had been handling explosives.

But the bureau hadn’t identified Dohrn as one of the possible Capitol bombers. The FBI and Justice Department remained focused on Washington.

As recent events have borne out, the federal government often underreacts to perceived security threats from the right and overreacts to those coming from the left.

The 1971 bomb blew at a crucial moment for Richard Nixon. On that particular morning he was winging his way to Iowa to shore up political support in the heartland. The president was struggling politically, his approval rating dropping. Republicans had lost a slew of congressional seats and governorships in the 1970 midterms, despite Nixon’s hope that moderates would approve the way he was handling the Vietnam War—stepping up the fighting while slowly withdrawing U.S. troops. Next year’s reelection campaign was looking fierce; polls showed him trailing the presumed leader among the Democratic challengers, Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine.

Nixon had largely built his career on antipathy to liberals and the left, and he didn’t need any additional fuel for his visceral distaste of the antiwar movement. A successful Spring Offensive threatened to not only complicate his Vietnam policies, and thus his second term, but also could distract from his grand plan to reopen diplomatic ties with China and remake the Cold War world.

One of his aides, Egil “Bud” Krogh Jr., who would later run the notorious White House “Plumbers” unit that plugged damaging leaks to the media and sought to undermine the president’s opponents, fired off a memo suggesting the Capitol bomb could be a rare opportunity. Handled right, it might counter the trend of “softer” support for the administration’s Vietnam policies from “middle of the road Americans.” The explosion, wrote Krogh, “is a chance for us to point out that we have not been tough for nothing. A bomb detonating in the breast of the Senate is as close as one can get to the heart of super-liberal thought in this government.”

Early in his presidency, Nixon had urged the FBI and Justice Departments to crack down harder on the antiwar movement, even contemplating giving written approval to illegal tactics such as burglarizing the homes and offices of activists. Before the Spring Offensive, Attorney General John Mitchell insisted the protests would turn out to be violent, no matter what organizers said. He secretly authorized warrantless wiretaps on the Mayday Tribe and three other groups. Now, the bombing fed the president’s belief that there wasn’t much difference between underground militants and peaceful protesters. Reporting to Nixon on the FBI’s hunt for the bombers, his chief domestic policy adviser listed the suspects: “It’s the Bernadette (sic) Dohrn, Rennie Davis bunch.”

The FBI shifted agents from all parts of the Washington field office to the case. They tailed Mayday activists, including four young people who drove north the day after the bombing, finally stopping them on a Pennsylvania highway. The agents, brandishing shotguns, searched their car but found no reason to detain them.

After all the investigating, only one person was taken into custody in connection with the bombing. She was a tall 19-year-old blonde from California named Leslie Bacon, who had been helping book musicians for the rallies. The FBI found witnesses who said they saw Bacon in the Capitol the day before the blast. When she denied it, she was charged with lying to the grand jury. Weather wrote an open letter to Bacon’s mother, saying she was innocent: “Mrs. Bacon, we cannot turn ourselves in to save Leslie. She is a committed revolutionary and understands this.”

At least a dozen other activists were subpoenaed before grand juries in New York, Detroit and Washington. All refused to answer questions. Some taunted the feds, like Judy Gumbo Albert, the driver of the car stopped in Pennsylvania, who declared of the bombing: “We didn’t do it, but we dug it.” Prosecutors had to decide whether to bring Bacon to trial anyway. But by the time the matter came up, the Supreme Court had issued a decision that effectively would have forced the government to disclose details of its surveillance. The Watergate burglars had just been caught, and the last thing the administration needed was another bugging scandal. Nixon himself ordered the Bacon case dropped. She and the other activists went free. Bacon has continued to say she had nothing to do with the bombing.

The Weather Underground continued to stage nonlethal bombings in the 1970s, notably a blast inside a Pentagon bathroom and at the State Department. (They called ahead on those, too.) When the Vietnam War finally ended, the group lost its center of gravity. By 1980, Weather had effectively disbanded. Dohrn, along with her husband and fellow member, Bill Ayers, came out of hiding. They didn’t go to prison. The government had dropped most charges against them for the same reason they couldn’t prosecute Leslie Bacon, and also because agents on a desperate hunt for clues had been caught conducting illegal break-ins at homes of the fugitives’ friends and relatives. The FBI’s overreach had backfired, but the era of left-wing extremism imploded on its own.

Kathy Boudin was one of the few who remained underground. In 1981, she helped a group called the Black Liberation Army rob an armored Brink’s truck outside New York City. Two police officers and a guard were killed, the militants were captured. Boudin and her romantic partner, David Gilbert, went to prison. She left their 14-month-old son to be raised by her closest friends, Dohrn and Ayers, who became academics in Chicago.

A grand jury subpoenaed Dohrn in the Brink’s case. When she refused to give a handwriting sample, she was jailed for eight months. Her friend Boudin spent 22 years in prison, winning parole in 2003, and now serves as co-director of the Center for Justice at Columbia University.

Neither has disclosed anything specific about Weather’s activities, but Dohrn has spoken in general about those days, with some regret if not quite an apology. “Now, nobody in today’s world can defend bombings,” she said in a November 2008 interview with Amy Goodman of “Democracy Now.” “How could you do that after 9/11, after, you know, Oklahoma City? It’s a new context, in a different context … the context of the time has to be understood.”

In the same interview her husband said: “I think that if we’ve learned one thing from those perilous years, it’s that dogma, certainty, self-righteousness, sectarianism of all kinds is dangerous and self-defeating.”

As a slogan of the 1960s went, what goes around comes around. That 14-month-old son who Dohrn and Ayers raised for Boudin? He became a Rhodes scholar, a lawyer and a public defender. In 2019, he was elected district attorney of San Francisco, a job once held by Vice President Kamala Harris. And on Jan. 6, as the pro-Trump mob attacked, Chesa Boudin sent out a tweet: “Hoping everyone who works in the Capitol is safe from this despicable effort to take down our democracy.”

Fifty years on, it seems remarkable how fast the 1971 attack faded from collective memory, even as it exercised a profound effect on the end of an era of political activism that would be unrivaled until the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. The bombing supercharged Nixon’s paranoia, leading the president and his aides to ramp up their crackdown on the New Left. They ordered the biggest, and most unconstitutional, mass arrests in U.S. history during the Mayday protests, rounding up more than 12,000 people. And then weeks later, the White House launched illegal measures to discredit Daniel Ellsberg, leaker of the Pentagon Papers. On Labor Day weekend, Krogh dispatched operatives to break into the office of Ellsberg’s former psychiatrist in Beverly Hills, searching for compromising material. Nixon’s men were field-testing the tactics they’d soon be caught using against their political opponents in the 1972 election. Thus, you can draw a line, if a dotted one, from the bombing to the demise of Richard Nixon in 1974. Donald Trump, meanwhile, still awaits the consequences of the Jan. 6 attack.