Legal immunity for police misconduct, under attack from left and right, may get Supreme Court review

WASHINGTON – The brutal death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police has re-energized a national debate over misconduct by law enforcement officials that the Supreme Court may be poised to enter.

The justices could announce as early as Monday that they will consider whether law enforcement and other officials continue to deserve "qualified immunity" that protects them from being sued for official actions.

The high court itself established that protection in a series of decisions dating back several decades, letting police off the hook unless their behavior violated "clearly established" laws or constitutional rights. Lower courts have used that standard to uphold almost any actions not specifically forbidden.

But in recent years, justices, lower court judges and scholars on both the left and right have questioned that legal doctrine for creating a nearly impossible standard for victims to meet and a nearly blanket immunity for those accused of misconduct.

The justices have been reviewing more than a dozen cases involving public officials' invocation of qualified immunity with an eye toward choosing one or more to hear next term. If they move ahead, it would indicate that at least several justices want to cut back on such immunity.

The timing of their review process on the heels of Floyd's death in Minneapolis is purely coincidental. But the 46-year-old African American man's treatment puts the issue in the spotlight.

"It's a vivid and tragic example of our culture of near-zero accountability for police officers," says Jay Schweikert, a criminal justice analyst at the libertarian Cato Institute, one of the leading advocacy groups seeking to limit or eliminate qualified immunity. “People understand that officers are rarely held to account.”

In one case the high court is reviewing, a Tennessee man was bitten by a police dog unleashed on him while he was sitting with his hands in the air. In another, a 10-year-old Georgia boy was shot in his backyard by police pursuing an unarmed criminal suspect. In a third, police in California searching for a gang member used tear-gas grenades rather than the house key given to them by his ex-girlfriend.

"You're supposed to have a warrant when you do stuff like this," says Robert McNamara, a senior attorney with the Institute for Justice, a libertarian law firm representing the California homeowner.

Police usually win

The Supreme Court has given police and other public officials considerable leeway in most cases where their conduct has come into question. In February, the court's conservatives ruled that the family of a Mexican teenager fatally shot by a U.S. Border Patrol agent cannot seek damages because of the border that was between them.

In 2018, they ruled that an Arizona police officer was within his rights to shoot a woman who refused to put down a kitchen knife. Three years earlier, they ruled that California police were equally entitled to protection after they forcibly entered the room of a woman with a mental disability and shot her.

A Reuters investigation earlier this month found that qualified immunity has shielded police accused of using excessive force in thousands of lawsuits.

And William Baude, a University of Chicago Law School professor and leading scholar on qualified immunity, documented in 2018 that in 30 cases spanning more than three decades, the Supreme Court found official conduct violated clearly established law only twice.

"Nearly all of the Supreme Court’s qualified immunity cases come out the same way – by finding immunity for the officials," Baude wrote.

Two of the court's current justices have pushed back against that trend from opposite ends of the ideological spectrum.

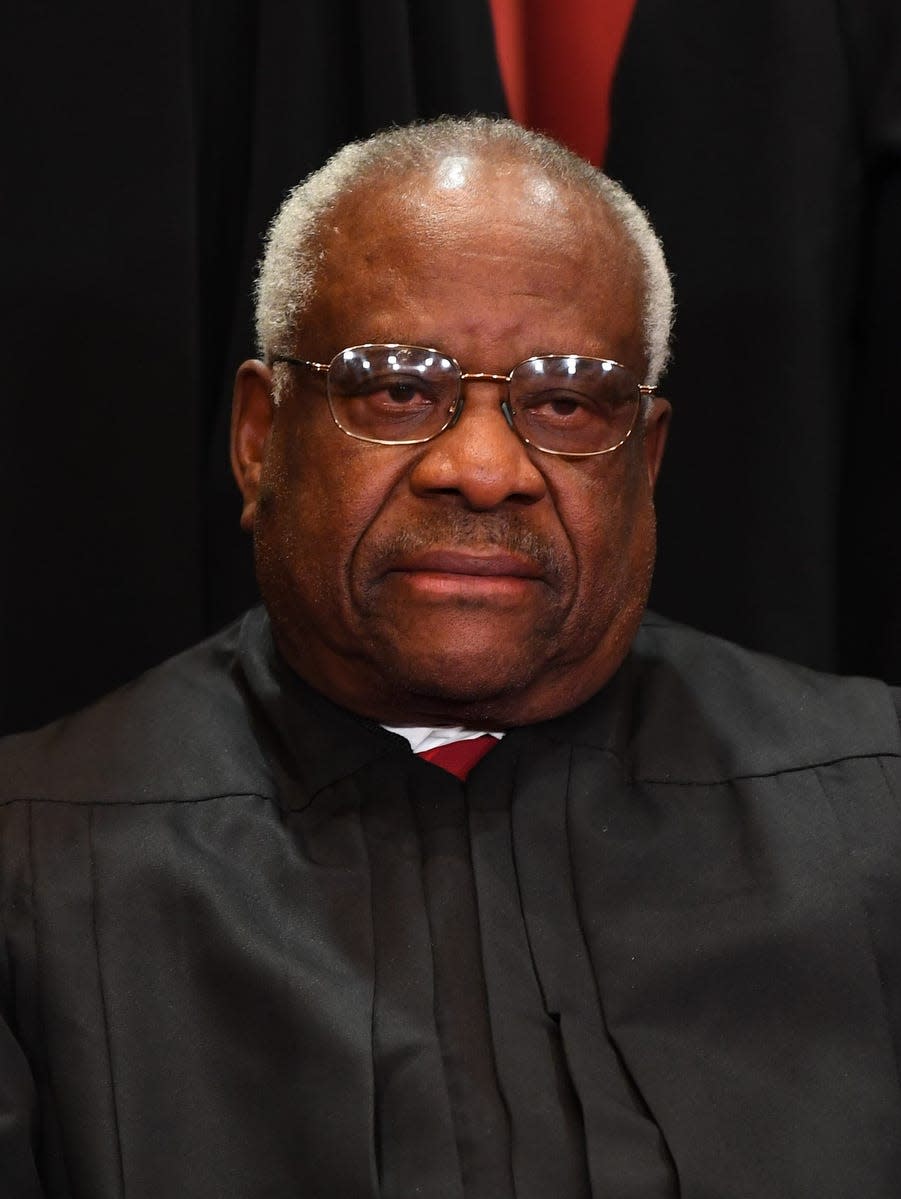

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, the court's most conservative member, has complained that the doctrine has no historical basis. The court, he said in a 2017 case, routinely substitutes "our own policy preferences for the mandates of Congress."

Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, arguably the court's most liberal member, said in 2015 that the court's "one-sided approach to qualified immunity transforms the doctrine into an absolute shield for law enforcement officers."

![Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor speaks during the 2019 Supreme Court Fellows Program annual lecture at the Library of Congress, in Washington Thursday, Feb. 14, 2019. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana) ORG XMIT: DCJL128 [Via MerlinFTP Drop]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/oEWwe6N_KihDrPTqZHQgHA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTcxMw--/https://media.zenfs.com/en-us/usa_today_news_641/362083c66e40c93b4b23d0d15329e6e0)

In one of the cases now pending before the high court, Judge Don Willett of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit complained that the Supreme Court's precedent "leaves victims violated but not vindicated. Wrongs are not righted, and wrongdoers are not reproached."

"Deeply broken"

In several of the lower court cases the justices are reviewing, groups on the right such as Cato and the Institute for Justice have been joined by several on the left, including the American Civil Liberties Union, MacArthur Justice Center and NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

"This is one of those issues that really unites left and right, because anyone with a coherent sense of justice can really look at what’s going on and see that it’s deeply broken," McNamara says.

Even if the justices agree to weigh in, however, it's not at all clear they would abolish qualified immunity or significantly scale it back. Chief Justice John Roberts, in particular, prefers baby steps to big changes in court precedent.

The justices earlier this month had a chance to second-guess a federal appeals court that granted immunity to police officers who stole more than $200,000 in cash and rare coins during a legal search. They refused to hear the case.

"This is essentially a court-created doctrine," says Andrew Pincus, an appellate lawyer who helps direct the Supreme Court Advocacy Clinic at Yale Law School. "They should take responsibility if it’s not working right."

Make your voice heard.: Join our Facebook group: ‘Across the Aisle, Across the Nation.’

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Police misconduct: Supreme Court may reconsider 'qualified immunity'