This legendary Black pianist died a forgotten man in New Jersey: the story of 'Blind Tom'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the early 1900s, residents living in the vicinity of an apartment building near 12th and Washington streets in Hoboken could hear the sound of piano playing most of the day.

What they did not know was that one of the most famous and exploited musicians of the time was living among them — much of the time out of view.

He was Thomas Wiggins, aka "Blind Tom."

A blind Black man, originally from Georgia, who was the first African American musician to perform at the White House, Wiggins earned devoted fans such as Mark Twain and made millions for his exploiters while seeing very little for himself.

He died in June 1908 at age 59 from a stroke in the Hoboken apartment he shared with his white guardian, Eliza Bethune. He is buried in the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn.

However, over a century later, books have been written about him, his music has been celebrated and performed, and he has gained some modern-day admirers like Elton John, who recorded "The Ballad of Blind Tom" on his 2013 album "The Diving Board."

Chatham resident Jim Riffel hopes to make a movie about him someday.

"His whole life — and the way he was able to perform — was like Ripley's Believe It or Not," Riffel said.

More:Pop quiz: 20 things to know for Black History Month

More:Morristown's first Black policewoman retires: 'Even the bad guys' respected her

The Real Thomas Wiggins

Mark Twain, the celebrated author, humorist and lecturer, was also a groupie. He followed Blind Tom Wiggins, whom he first saw in performance three nights in a row in 1869, and recounted that experience for a California newspaper.

Twain swooned that "he swept [his audience] like a storm, with his battle-pieces; he lulled them to rest again with melodies as tender as those we hear in dreams." The famed writer then raved about Wiggins' unique ability to "stand off at a distance, and face the audience, with his back to the piano, and you may strike any key you please, and he will tell its name and its color."

Ironically, it was Wiggins' blindness from birth in May 1849 that allowed him to become a prodigious musical talent instead of a slave on a plantation in the western part of Georgia.

Various documented sources tell of this youngest child of enslaved parents Charity and Mingo Wiggins, who due to his disability was spared the brutal work that his family was forced to do during that time. Blindness provided a young Thomas with the freedom that his owner's children had — to play and explore their surroundings.

At an early age, he discovered the piano of the owner's daughter, and he soon was playing tunes on it based on sounds he heard around him. That owner, Gen. James Neil Bethune, saw an opportunity to make a living off the young boy's musical gifts. At 8 years old, Wiggins was already performing at various venues in Georgia when he was leased out to a promoter who would make him even more profitable to his handlers.

The 2004 book "African American Lives" mentions in an entry about Wiggins that he was billed as "The Wonder Negro Child," a grotesque moniker devised by his promoter, Perry Oliver, that played into the stereotypes of Black people and the popularity of freak shows of the time. It also trivialized his virtuosity in tickling the ivories as he expertly played pieces by such classical music giants as Bach and Verdi as well as his own compositions in front of prominent figures like President James Buchanan in 1857.

Wiggins was also robbed of his humanity by journalists of the time, as is evident from descriptions of him while he toured Europe in 1866 and 1867 as a "poor, half-demented lad" and "black, blind, a fool, and a musician." Some failed to see beyond his eccentric stage manner, which included introducing himself in the third person and mimicking public figures and nature sounds, which some scholars believed was a result of autism.

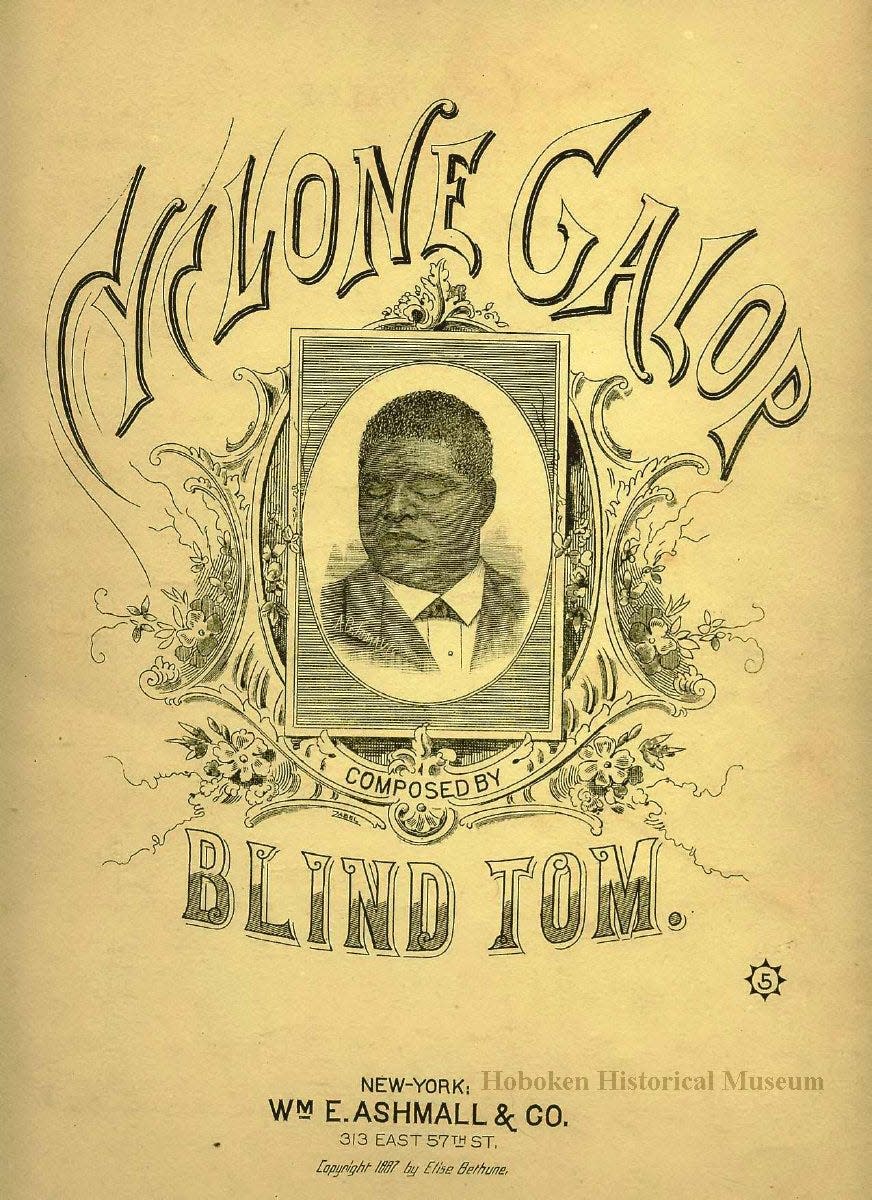

Brooklyn-based pianist and composer John Davis has studied the music of Wiggins for nearly three decades. He has performed a one-man show over the years called "Will the Real Thomas Wiggins Please Stand Up?" and recorded an album in 2008 of Wiggins' works, including "Cyclone Galop" and "The Battle of Manassas."

Davis, in an interview with NorthJersey.com, said despite Wiggins' being one of the most popular Black musicians of the time, he did not get his due as a serious musician when he was alive.

"He was always promoted as a kind of circus freak, and this ultimately contributed to him being dismissed in the annals of American music upon his death," Davis observed. "But a point of fact, the music, actually the published music, really bears out that he was a serious composer, and probably by all accounts an accomplished pianist."

Forgotten in New Jersey

Wiggins' time in New Jersey came in the last two decades of his life, when his star began to fade.

Some of the decline was not of his making, as Wiggins was weighed down by litigation dating back to his youth. It was usually between various members of the Bethune family over who would have guardianship of a musical prodigy who commanded earnings of hundreds of thousands of dollars annually with his performances.

Music scholar Geneva Handy Southall, in her 1999 book, "Blind Tom, The Black Pianist-Composer Continually Enslaved," wrote of how Charity Wiggins resented that she could not be near her son because he was taken away from her due to these legal battles.

Among those held responsible for the separation was Eliza Bethune, the widow of John Bethune, son of Wiggins' longtime owner. Bethune gained custody of Thomas Wiggins in 1887 after a three-year legal battle with her husband's family and would cut his mother out of sharing in his wealth.

Bethune, after marrying the attorney representing her in the custody battle, Albrecht Lerche, used the money that Wiggins earned from his playing to purchase a country home in the Navesink Highlands in Monmouth County, where Tom would live part of the time, with the rest spent in a tenement building in New York City's Greenwich Village.

Davis said that based on his study of Wiggins, he learned that he and Eliza moved to what would be their final residence in Hoboken in 1903, after her divorce from Lerche.

"There's little bits of records of him there. I think there's an article about how he was an odd figure that local residents would see from time to time," Davis said. "They did hear piano playing coming from that apartment, but he was this mysterious figure."

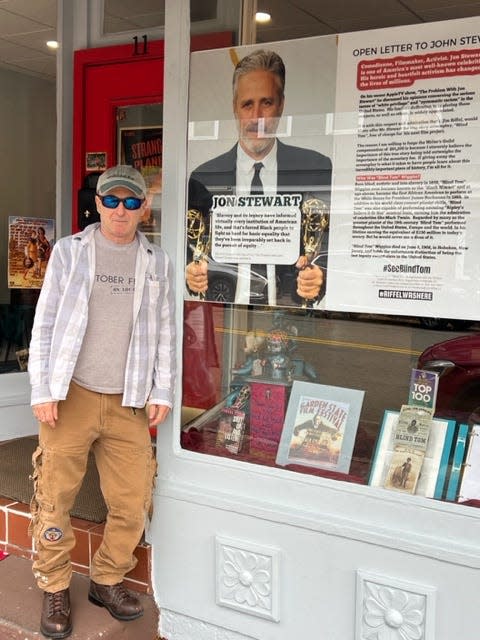

Riffel said learning about Wiggins in the early 2000s prompted him to write a screenplay about Wiggins that he has tried to get into the hands of celebrities including Whoopi Goldberg and Jon Stewart. Riffel tried to interest Stewart through an open letter posted last year in the window of his Strange Planet Outsider Art Gallery on Passaic Avenue in downtown Chatham, offering his screenplay to Stewart, but did not hear back from him.

Riffel hopes that the public will learn more about this fascinating historical figure.

"He is probably one of the most unique, talented and important figures in music history. I wish that more people would know his whole story, all the aspects of his story," Riffel said.

Ricardo Kaulessar is a culture reporter for the USA TODAY Network's Atlantic Region How We Live team. For unlimited access to the most important news, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: kaulessar@northjersey.com

Twitter: @ricardokaul

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: New Jersey was the final home for legendary Thomas "Blind Tom" Wiggins