Let It Be Director Michael Lindsay-Hogg's Words of Wisdom on His Misunderstood Beatles Documentary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Express/Express/Getty Images

It's Jan. 29, 1969, and director Michael Lindsay-Hogg has a problem. He has just days to improvise an ending for his film with the Beatles, and they are not making it easy for him. This is keeping with the theme of the month-long production, a logistical nightmare that has morphed from a television concert special into a cinéma vérité documentary midway through the shoot. The intimate scenes of the band writing and rehearsing are extraordinary, but he needs a finale, a climax, some kind of payoff — one that doesn't subject them to the hassles and hysteria that plagued their touring life at the height of Beatlemania. For a time, one idea seemed to stick: an unannounced performance on the roof of the group's Apple Records headquarters in Central London. The semi-public nature of the gig seemed like a good compromise. Yet now, huddled in their studio six stories beneath the proposed venue, there's dissent in their ranks.

With deadlines looming, Lindsay-Hogg is left with the unenviable task of extracting a rapid decision from his mercurial subjects, who also happen to be the most famous people on the planet. "What are we going to do? I'm going crazy," he wails. "I mean, I know that's what I'm supposed to do, but I'm really going crazy…We ought to figure out what we're going to do." Paul McCartney tries to talk him off the ledge, but George Harrison is less convinced of the whole rooftop scheme. "You mean, you still are expecting us to be on the chimney with a lot of people, or something like that?"

"George, George — 'expecting' is not a word we use anymore," Lindsay-Hogg replies, his theatrical exasperation barely masking the very real sensation just below the surface. Bossing around a Beatle would definitely not have the desired effect. Instead, he offers "thinking about" and "hoping" as more appropriate phrases for the indecisive collective. Harrison remains unmoved. "You know, whatever. I'll do it if we've got to go on the roof. But, I mean, I don't want to go…'Course I don't want to go on the roof!" It's an inauspicious start for one of the most fabled concerts in rock history, which took place the following afternoon.

The scene is part of 56 hours Lindsay-Hogg shot for what became his 1970 documentary, Let It Be. After half a century in the vault, the unused footage has been recut by fellow filmmaker Peter Jackson into the three-part, eight-hour epic Get Back, which debuts Nov. 25 on Disney+. No stranger to trilogies (see: Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit) or vivid historical restorations (They Shall Not Grow Old), Jackson has described his latest work as a documentary about the making of a documentary. While the Beatles are naturally the focal point, the plot hinges on Lindsay-Hogg, the increasingly harried director at the center of the action. "Peter said early on to me, 'I think you're going to have to be in this movie,'" Lindsay-Hogg tells PEOPLE. "He couldn't cut the conversations out because they were part of what was going on at the moment. They showed the Beatles dynamic, which is what we were interested in illustrating."

The fact that Lindsay-Hogg was able to complete a film at all under such conditions is a minor miracle. Yet the problems continued even after shooting wrapped. Delayed for over a year due to the Beatles' mounting business disputes, the documentary hit theaters in May 1970, just weeks after the band publicly announced their split. The timing of its release ensured that it would forever be linked with unhappy news. The fact that it had been filmed nearly a year and a half earlier seemed to matter little.

Let It Be was a victim of history. Over the subsequent decades, it's been maligned as a dismal document of their dissolution. Even the Beatles distanced themselves from the project, declining to attend the premiere and ultimately withdrawing it from home video in the early '80s. Its scarcity has further harmed its reputation; older fans are forced to rely on their initial impressions, often formed in the bitter aftermath of the breakup, and many younger fans are unable to access the film (outside of grainy bootlegs) to judge for themselves. The result is a negative feedback loop that continues to this day.

Get Back is being touted by many critics as a lighter, more uplifting alternative to Lindsay-Hogg's film. Ringo Starr said as much during a recent appearance on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. "I used to moan because the original documentary was very narrow," he said. "There was no joy in it...Even though we had arguments, like any family, we loved each other, you know, and it shows in the [new] film."

Lindsay-Hogg accepts these critiques with good humor — he's had practice over the years — but he understandably finds it all a bit galling. "Let It Be came out a month after they said they were breaking up, so people said, 'Oh, it's the breakup movie.' Well, it wasn't," he explains. "It's frustrating because it colored the way Let It Be has been looked at for 50 years. When Ringo says, 'Well, I don't like the movie…' he hasn't seen it for 50 years and doesn't really know what's in it anymore."

To be sure, the film is filled with playful jams, jokes and touching moments that depict their close friendship. But gone are the days when the Beatles were the four-headed monster (as Mick Jagger called them), clad in identical Dougie Millings suits and Anello & Davide boots, joined at the hip through endless nights sharing stages and hotel rooms. "Watching [Let It Be], you get a sense that they're not young men anymore," says Lindsay-Hogg. "John is 28, Paul is 26, George is 25, Ringo is 28. They were pulling apart not because of enmity, but because they just were starting to go in different directions. All their performing success was behind them. They just didn't want to do it anymore."

The transition had begun around the time Lindsay-Hogg first began working with the band in the spring of 1966. Having made a name for himself as a director on the British rock program Ready Steady Go!, he was hired to oversee what were then known as "promo clips" for the Beatles' latest single, "Paperback Writer" and the B-side, "Rain," inadvertently laying the groundwork for MTV in the process.

Weeks after the shoot, the Beatles embarked on what would be their final tour before retiring from live concerts. For the next two years, the band existed solely as a studio entity. Lindsay-Hogg wouldn't work with them again until the fall of 1968, when he was recruited to direct visuals for the songs "Hey Jude" and "Revolution." The former featured the band performing on a soundstage at Twickenham Studios amid an assembled crowd of onlookers representing all manner of races, sexes and creeds. The simulated gig proved immensely enjoyable for the Beatles. It was the best of both worlds: all the fun of a live show within a safely stage-managed studio bubble. The experience sparked the notion of a full-scale televised concert.

So began the saga of Let It Be. The Beatles booked the same soundstage and the same director, and set a date for Jan. 2, 1969 to begin filming rehearsals for a proposed concert of all new songs — location TBD. "We all were thinking about where [the show] would be," Lindsay-Hogg recalls. Starr proposed the Cavern, the dank cellar that had been their Liverpool home base as a young band. "I said, 'Well, the Cavern's a great place, but maybe you've outgrown the Cavern now.' Then someone suggested a field. And I said, 'Well, a field is nice. It's got trees, but probably not much more than that…' I suggested this Roman amphitheater in the middle of the desert in Libya. The music would start at dawn and go out over the desert. And by nighttime people would come and listen to the music in the amphitheater lit by torches. That idea flew for a while."

A posse of assistants got their malaria shots and were poised to scope out the location when the film lost a star. On Jan. 10, Harrison walked out of the rehearsals and announced that he was leaving the band. Though hardly expected, it was also not completely out of the blue. The tensions that had set in while recording The White Album the previous year had magnified. Yoko Ono often gets the blame due to her constant presence (at Lennon's urging). Though her attendance undoubtedly disrupted the delicate interpersonal dynamic, numerous factors led to their dissatisfaction, ranging from Lennon's substance abuse issues, the clinical atmosphere of the soundstage, and even the early morning call times. Harrison's frustration over his second-class status in the band was merely the most acute of the issues.

Many fans point to a disagreement with McCartney over a guitar line as the catalyst for his resignation. Included in Let It Be, the scene has become — aside from the rooftop concert — perhaps the most famous moment in the film. Frequently dissected by fans, it's cited as proof positive that the Beatles were at each other's throats throughout the sessions. Lindsay-Hogg, for his part, doesn't buy it. "Tension is part of doing the job in the artistic world. That's what you do. Well, I want it this way! You want that way! You can do it that way this time, but I'll do it that way next time. Whatever. That's all that was going on between them. But people read into 'Or I won't play at all!' as though that was the most momentous disagreement since America declared war on England…"

Harrison's departure was temporary, but it put a permanent halt to the televised concert. "George agreed to come back on the proviso that we didn't talk about a TV special anymore," says Lindsay-Hogg. "He decided that he didn't want to be part of an extravaganza. He just wanted to work on the music. I think he was looking to shore up his own credentials as a songwriter. Since they began as teenagers, it had always been Len-Mac or Mac-Len for the songwriting credits. I think he was starting to feel, 'Hey, inside me is a really good songwriter!' Any frustration he was feeling while we were doing what turned into Let It Be was not in a big pop-the-boil festering way, but just feeling frustrated that he couldn't get his old friends to let him in artistically. In no way was George a villain at all. He just had certain goals that he was looking to achieve, which were musical goals."

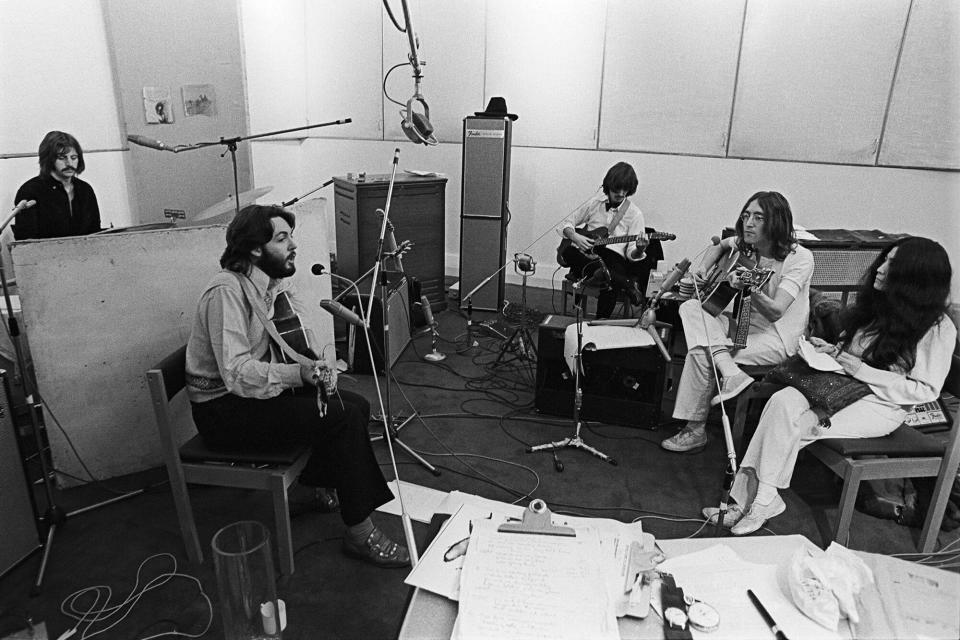

Rehearsals at drafty Twickenham soundstage were abandoned, and the group decamped to their new studio in the basement of their Apple Records office building to continue work on what was shaping up to be a new album. Lindsay-Hogg recalibrated his shoot as quickly as he could. "Overnight we went from doing a television special to making a documentary," he laughs. "Okay, you gotta roll with it. I mean, these are the Beatles after all! I suppose we could have stopped, but we thought we've put [all this effort] into this. Plus, no one had ever seen the Beatles rehearse before. No one had ever seen how they make music. No one had seen how they interact with each other creatively." And so, it was decided, the show would go on.

Ethan A. Russell / © Apple Corps Ltd.

The studio sessions were significantly more cheerful than the soundstage rehearsals, but soon it became obvious that some sort of common goal was required to structure the documentary. "We needed to have someplace where this was going," says Lindsay-Hogg. "Yes, we could have rehearsals of 'The Long and Winding Road' on day one, day four, day five...It's a great song, we should all be so lucky! But even though it was the Beatles, the treads in the tire were getting a bit thin because we weren't going anywhere with this stuff. We needed to have a conclusion of the work we'd been doing. It seemed to me we ought to do some kind of performance." Something unusual, something visually compelling, and — crucially — something quick.

It's unclear exactly who came up with the concept of playing on the roof. Engineer Glyn Johns has claimed credit, while others say Starr had the initial brainwave. Lindsay-Hogg maintains it was his idea, born primarily out of desperation. He says he broached the notion over their midday meal. "I said, 'I think we need a conclusion.'" This basic premise was a tough sell. "Yoko said, 'Are conclusions important?' Now, this was a double whammy because, first of all, she's a bright woman. She came out of the New York art scene in the '50s and has her own artistic opinion. Not only that, but she also was the girlfriend of John Lennon. I wanted to be courteous, but also push the idea as far away as possible. So I said, 'I know what you're talking about. Conclusions are not important most of the time, but it could be!' I figured that was as ambiguous as I could get it. And then I said, 'We didn't do it at the Cavern, we didn't do it in a field, we didn't do it in an amphitheater in Libya. So why don't we do it on the roof?'"

The idea was received with a degree of skepticism, notably from Harrison, the most reluctant performer. "I wasn't sure it would fly because by that time no one was thinking about anything other than making an album," Lindsay-Hogg admits. "The whole idea of presenting them singing their songs was completely out the window. They were thinking about music, but they weren't thinking about anything that was my job to think about."

Eventually they warmed to the idea, and preparations were hastily carried out for a show on Jan. 30. An impromptu stage was constructed out of scaffolding planks, and yards of cords and cables were snaked down the stairwell to the recording console in the basement. Lindsay-Hogg dispatched an army of cameramen to cover the concert from all angles, sending a crew into the street, onto adjacent buildings, into the Apple reception area, plus five on the roof itself.

But minutes before they were due to play, the Beatles got cold feet — figuratively and probably literally. "We were all standing in a little room underneath the staircase which went up to the roof," remembers Lindsay-Hogg. "I thought, 'They'll do it. Why would they be standing here under the roof if they weren't going to do it?' But then Ringo said, 'It's really cold up there.' He was thinking of the guitar players and their fingers, because it was like 46 degrees and a biting wind. Then George said, 'What's the point?' It was like the electoral college, and we had two votes going the wrong way." McCartney had been the primary motivator behind the whole project in a Gatsby-esque attempt to recapture what they had shared when they were young. He saw this as the do-or-die moment. "Paul started to push: 'We need to do something.' He meant they needed to become active again. They needed to become interactive again. They needed to be connected to people again. They needed to go back to what they used to love doing, which is playing rock and roll. But they didn't quite have the votes yet. There was a silence and then John said, 'F— it. Let's do it.'"

RELATED: Getting Back to 'Get Back': The Long and Winding Saga of Glyn Johns' Lost Beatles Album

Ethan A. Russell/Apple Corps Ltd

Just after 12:30 PM, the four friends blasted the sedate West End side street with an amped-up dose of their latest musical offerings. The cameras below recorded the puzzled reactions of listeners on the sidewalk, confounded by the earsplitting sound from on high. Some were young office workers, grateful for a break in the lunchtime monotony. Others were stuffy businessmen and tailors, longtime denizens of Savile Row, who were less charitable in their reviews: "I think it's a bit of an imposition to absolutely disrupt all the business in this area," sniffed one besuited snob. It was no doubt one (or several) of their ilk who alerted the Metropolitan Police. They needn't have bothered — the West End Central Police Station was located just a few doors down from Apple headquarters. Before long, a fleet of slightly sheepish Bobbies elbowed their way onto the roof and put a premature end to the show.

Lindsay-Hogg got his ending for the documentary, and it was better than he could have ever anticipated. "I didn't expect how thrilled they were to be playing together. I mean, it was a weird occasion. We're on the roof, the crowd's down below, the police came up. It wasn't quite what anybody was expecting, but they really loved playing with each other. You see it in the way they look at each other when they smile, the way they harmonize with each other, and the way they get on with each other. It's really beautiful. And they know that what's happening with them is special." Though they weren't physically at the Cavern, they may have well been. For 42-minutes, they turned back the clock. As they ran through nine songs, the pressures that had been building for years were lifted. Even Harrison cracked a smile.

The cameras captured the Beatles' performing live for what turned out to be the very last time. The moment is made all the more poignant by a tongue-in-cheek sign off from Lennon as they acknowledged the smattering of applause from the thin crowd of onlookers and technicians: "I'd like to say thank you on behalf of the group and ourselves, and I hope we passed the audition." Lindsay-Hogg still chuckles at the moment. "If you were going to script it, who could've written a better line?"

Like all good things, it couldn't last. Once the music ended, business woes took centerstage and the future of the Let It Be project was cast into doubt. "It got shunted aside because Apple was imploding and the Beatles were fracturing. The issues were financial, but then financial problems always turn personal. Things which had been brewing subterraneanly between the four of them blew up. Don't forget, they'd been together since they were 15 and 16. There were various grudges and old rancor, and so then they broke up." By the time the documentary saw the light of day in May of 1970, the now ex-Beatles could hardly care less. As far as they were concerned, it was ancient history.

"I was telling Peter Jackson the story of Let It Be and how it went from being a TV special to a documentary to up on the roof, and then they kind of abandoned it. They didn't support it," says Lindsay-Hogg. "I was dealing with the distributor myself, trying to lock in the theaters and dates. And Peter said, 'So except for you, Let It Be was really an orphan.' Of all the remarks that have been made about it ever, that is the most on the money."

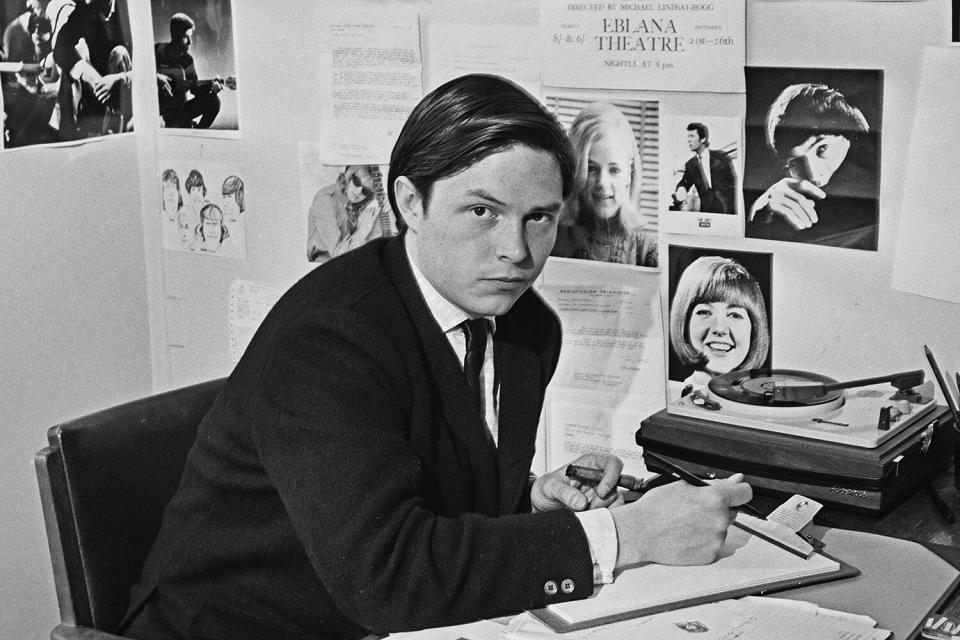

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images Michael Lindsay-Hogg

Lindsay-Hogg first learned of Jackson's involvement three years ago after getting a call from Jonathan Clyde, the Director of Production at Apple. "He invited me to tea and said, 'Peter Jackson's seen some of your footage and he's interested in having a whack at. How would you feel about that?' And I felt great, because I don't want to do it again. I did it. I don't want go in the cutting room and have to look at 56 hours again. I didn't want to be involved in the cut at all, but every so often [Peter] would email and say, 'Do you remember what happened on day six?' Or, 'What do you think of this little bit?' So he's been very inclusive."

Rather than worry that Jackson's documentary will supplant his own, Lindsay-Hogg sees the two projects as complementary works that collectively offer a full portrait of this fascinating period in the Beatles' final year together. "They're totally different movies made 50 years apart. They're not competitive in any way. One's this and one's that. I'm looking forward to seeing the fullness of Peter's work, because he's been very, very sympathetic toward Let It Be."

Naturally, Jackson's film will be more comprehensive, simply because he's working with a much larger canvas. Lindsay-Hogg's film was 89 minutes, compared to Jackson's 468 minutes spread over three installments. And also, Jackson contended with far fewer editorial constraints than Lindsay-Hogg. Decades removed from the animosity of their split, the surviving Beatles have mellowed and taken a sunnier view of their own history and legacy. "Peter was dealing with an entirely different set of plates and cutlery than I was," says Lindsay-Hogg. "I know that he used some of the stuff that I cut out." Back in the '60s, the Fabs were a little more particular about what scenes made it into the film. "The first rough cut I showed them was 40 minutes longer than what played in the end. There were a few things that they wanted out, which they indicated to me. They weren't saying, 'Well, you got to take that out!' It was more like, 'Do we really need that…?' That was their way of putting it."

Among these moments were anything that hinted at Harrison's temporary walkout. "One of them said, 'George didn't [officially] leave. So why put it in the movie?' At that time they were still together, and we easily cut it out," he explains. "They weren't against being portrayed as they actually were: people changing, becoming more mature, going their different ways but loving each other — all of that. But they wanted ideally for the Beatles to appear to be intact at the end of the movie."

Jackson, on the other hand, had no such restrictions. He also had access to a remarkable piece of audio that documented the moment of Harrison's exit, a legendary exchange in which the guitarist (reportedly) delivered the withering parting line, "See you 'round the clubs." The incident occurred during lunch, a time when Lindsay-Hogg's crew weren't usually present. But sensing a storm brewing, the director got creative. "When I knew there was something going on [between them], I bugged a flower pot at lunch. But I didn't get what I wanted, because there was too much ambient noise. The flower pot mic picked up the cutlery sounds." For Get Back, Jackson employed cutting-edge technology to strip away the extraneous noise, revealing this conversation, and many others, for the first time.

In Lindsay-Hogg's opinion, Jackson's forensic mind and intense passion make him the ideal steward of this cache of unreleased Let It Be footage. "Technically, Peter's movie is going to be fascinating to watch. But also, he loves the Beatles. He's turned out to be a really wonderful guy. Not only talented, but affectionate and concerned and curious all the way."

Rebecca Sapp/WireImage

Now 81, Lindsay-Hogg lives in upstate New York with his family. Since Let It Be, he's enjoyed an enormously successful career in film, television and theater, helming projects for Neil Young, the Who, the Rolling Stones and Simon & Garfunkel's historic 1981 reunion concert in Central Park. Of course, he maintains a soft spot for the Fabs. In 2000, he directed the TV movie Two of Us, a deeply touching study of Lennon and McCartney's post-breakup relationship.

Like many Beatles fans, he hopes that his most famous project will enjoy a second coming in the wake of Jackson's documentary. "The plan is that Apple is going to find a way to release Let It Be at some point after Get Back. It could be limited theatrical, it could be streaming, it could be DVD. But their plan is to let it out again in light of Peter's movie."

Until then, it remains a glaring absence in the band's storied canon. Let It Be is both a period piece and a self portrait. Most of all, it's a monument to art under pressure. Despite the strife, Lindsay-Hogg made his movie. And the Beatles got back to where they once belonged.