Let Judith Light Guide You

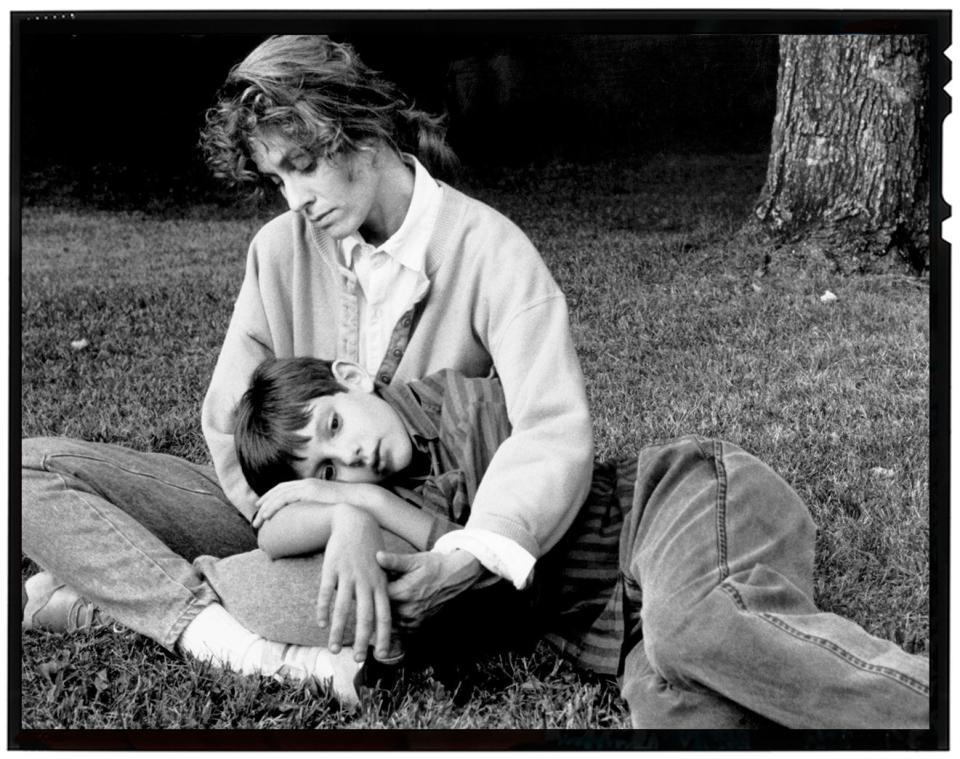

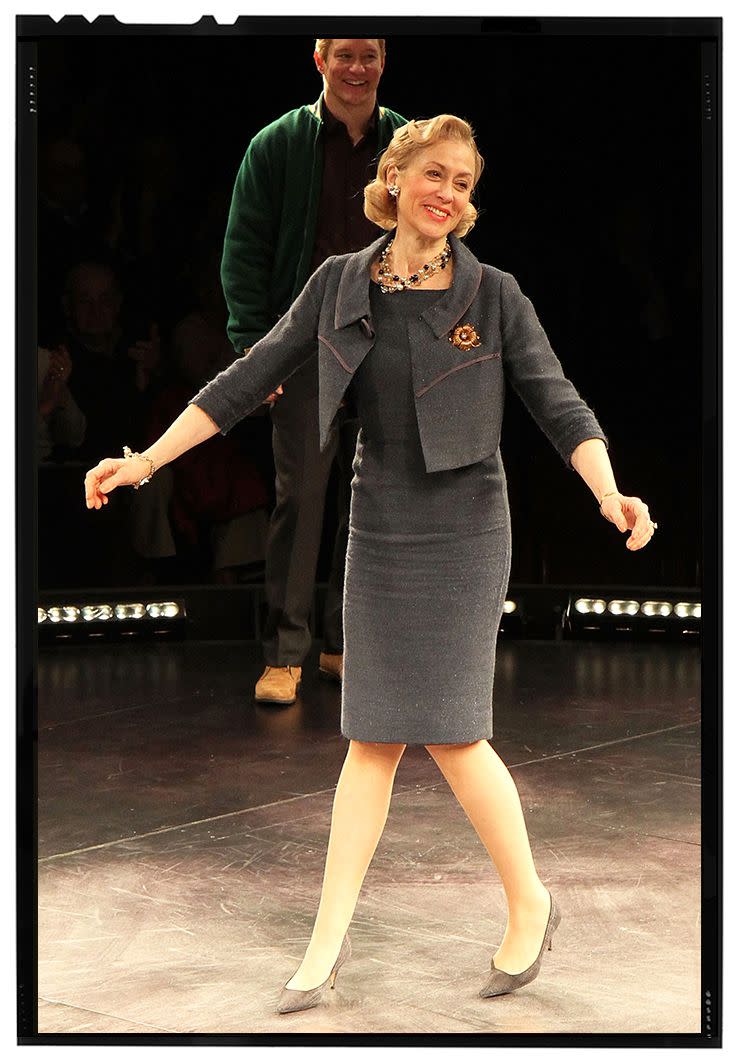

In the Ryan White Story, she’s a single mother, full of righteous fury, fighting for a hemophiliac son whose AIDS makes him a pariah in their small town. In Ugly Betty, she’s an alcoholic fashion magazine publisher with a rap sheet for murder. In Transparent, she’s an emotionally adrift Jewish matriarch, belting out tearful Alanis Morissette numbers for a cruise ship audience. In Queen America, she’s a haughty society doyenne ruling over the pageant circuit with a cryptic smile. On stage, in the Jon Robin Baitz play Other Desert Cities, she gives a performance that the New York Times’ Ben Brantley once lovingly described as “a deteriorating coat hanger.” Can your fave deliver Container Store fubulosity and win a Tony for it? Yes, she can. Because your fave is Judith Light.

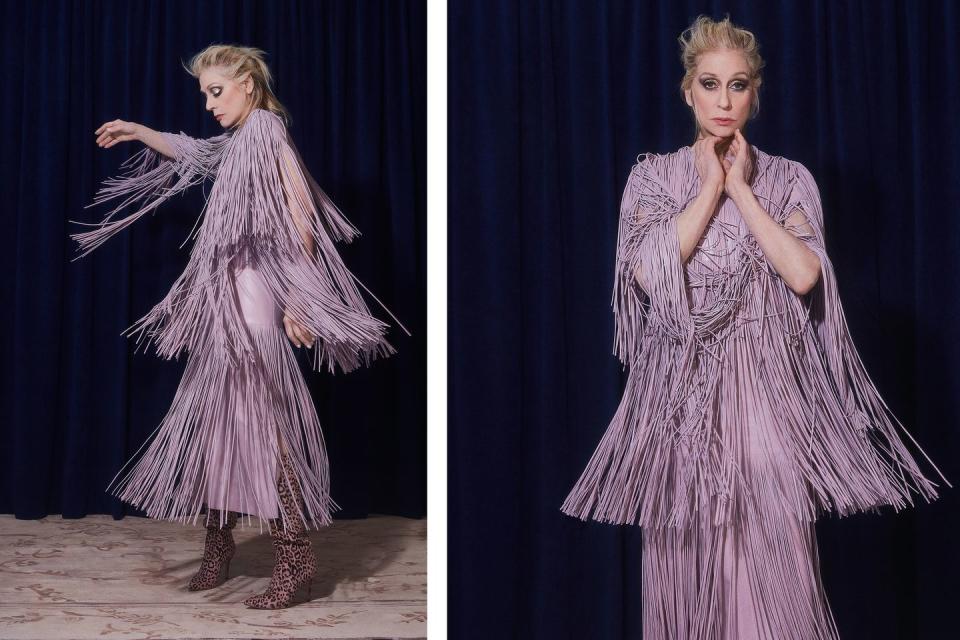

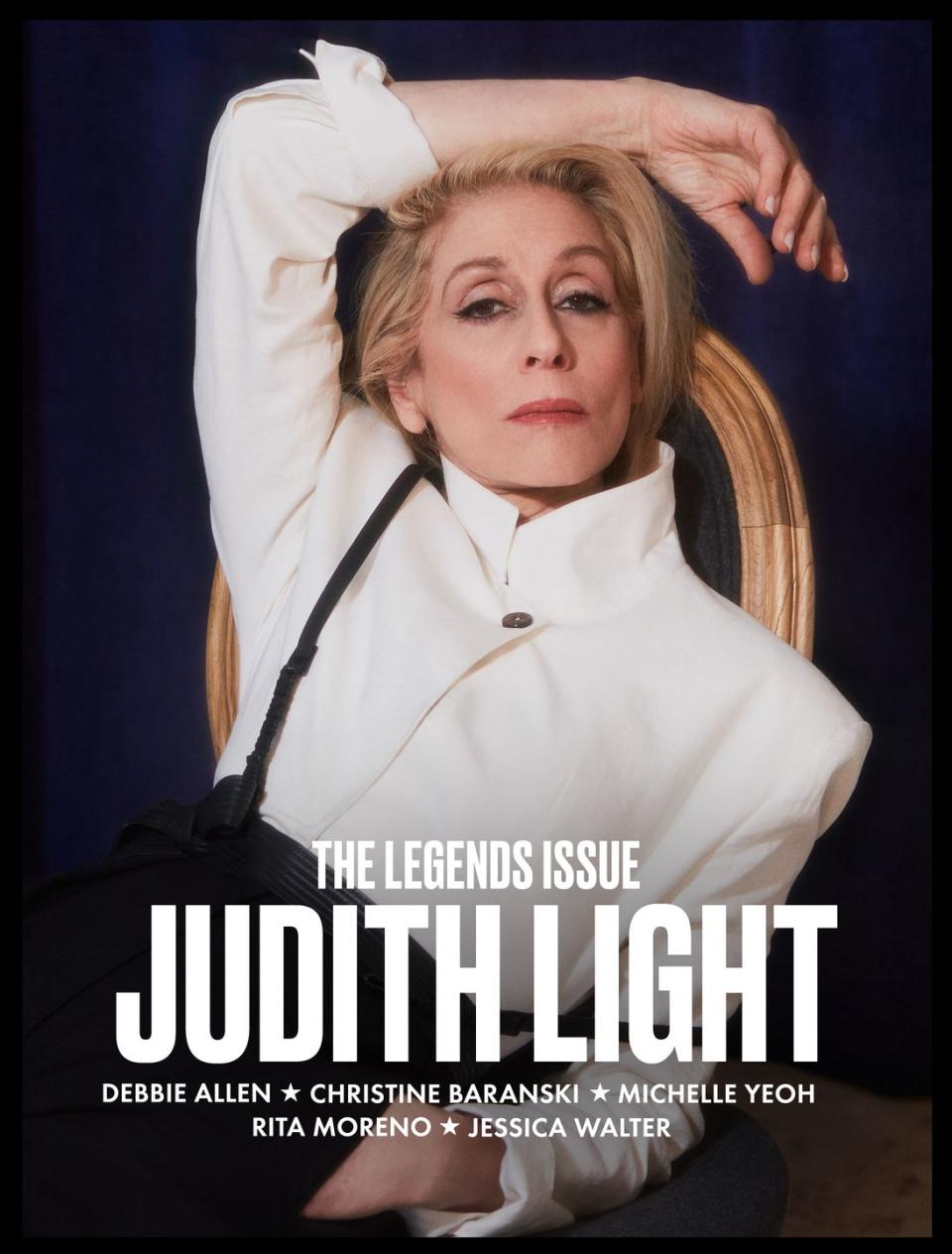

Witness her on the red carpet, serving realness so real that reality itself starts taking notes. Witness her on the set of a shoot, draped in a lush Bottega Veneta coat over a silky, golden jumpsuit, curled up on the floor, channeling Anna Karenina with a spontaneous wail: “The traaaaaaains!” Witness Judith Light in action. Category: every category. Tens across the board.

Light should be a diva. At 70, and after 40 years of constant reinvention, she’s earned the designation. But she’s no diva. She is, in fact, deeply humble. Not “I have to say something nice about her for this interview” humble. Like, actually humble. We speak on the phone as Light is driving to JFK to catch a flight to Los Angeles. But after we hang up, Light calls me back twice-count ‘em, two times-to offer more information she thinks I’ll enjoy or to sing the praises of other collaborators, because there are so many, and they can’t be contained to one call from a car or one more from an airport lounge or even one more from on board a plane as flight attendants prepare the cabin for departure. It gets to the point where Light is sitting on the tarmac, squeezing a couple more compliments in-Hamilton director Thomas Kail is “charming, smart, funny”; veteran actress Katherine Helmond “is a living example of how to operate in the business”; theater producer Daryl Roth “has impeccable taste”-before takeoff. By now, we’ve been talking for hours, on and off, and if not for TSA regulations, I could have talked to Judith Light forever.

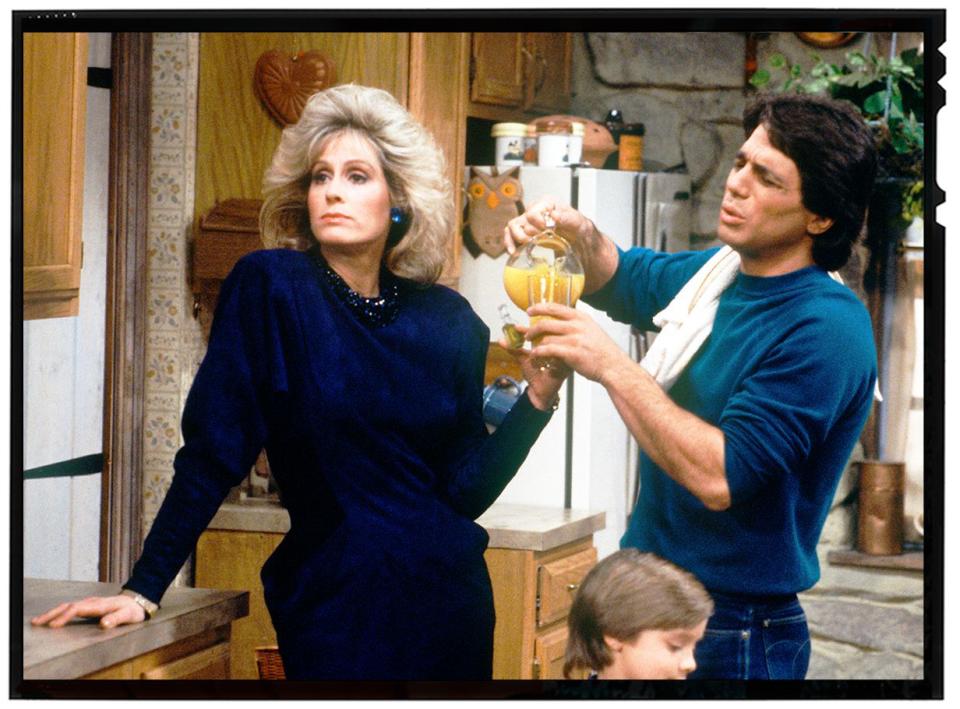

Light's onscreen career began on One Life to Live and a few television guest spots before being cast as Angela Bower, a working mom and Tony Danza’s sparring partner on the sitcom Who’s The Boss? The show delivered Light her first defining role, but its title also underwrote everything that came after it in her career, whether it was in film, TV, or theater. Who’s the boss? Answer: Judith Light, who you’re never not happy to see walk on screen, who commands your attention, who elevates even the projects that don’t deserve her. Offscreen, she’s been a frequent activist on behalf of people with HIV/AIDS and the LGBTQ community. It’s work that continues to this day through speeches, appearances, and service. Not to mention in her choices of projects: there was The Ryan White Story; the film Save Me, about the dangerous practice of gay conversion therapy; her Emmy-nominated role in Amazon's Transparent, as the ex-wife of a transitioning woman; and her Golden Globe-nominated portrayal of Marilyn Miglin, the perfume magnate whose closeted husband was murdered by Andrew Cunanan in FX's The Assassination of Gianni Versace: American Crime Story.

And there’s so much more to come. As she prepares for the two-hour finale of Transparent and then a slate of new projects, some of which she’s producing with her husband, Robert Desiderio, Light reflects on her career, from her triumphant return to theater to her status as a red carpet maven. As she does, the word “gratitude” is always on her lips. For Light, it’s not a buzzword, but a fully realized worldview, a spirituality she observes by praising coworkers, past and present, speaking with awe not of the career she built but of the response it’s elicited time and again. "All of this is about putting myself out there in the world," she says, "coming from gratitude for what is presented.” The gratitude is all ours.

Early in your career, you told your late manager, Herb Hamsher, that you hoped to achieve celebrity so that you could use it to better advocate for things you believed in, and the larger platform for service. Where did that come from, and how do you feel like it's played out?

I think it came in large part from my parents. They were always about doing service, helping other people. I think that's what we're here to do, to help each other in this life. It's always been something that I have felt very strongly about. I also knew from the time I was very young that I wanted to be an actor. So, when I said that to Herb years ago, it was really about finding the kind of support that would help hold that context for me.

Particularly in the ‘80s, I tried to serve by talking about HIV and AIDS, and about the level of homophobia that I saw against the LGBTQ community. I knew that if people knew me, if I had a voice, I could be in some way a support to all my friends who were dying, and to the people who were in that extraordinary community. I always wanted to be useful, and used. There were people who wrote to me after I did The Ryan White Story for ABC [in 1989] and said, "I'll never watch you again." And I thought, Wow, okay, that's also partly what comes with the territory.

Did you ever think you’d get that kind of reaction from viewers?

I didn't think about it. I felt that there was an injustice, and I felt strongly about it. I didn't think, Oh goodness, how is this going to affect my career? I saw what was happening, and I thought it was unconscionable, divisive, and cruel, and it had to be addressed. I saw people like Elizabeth Taylor, who was standing up for her friend Rock Hudson and going to speak in front of Congress, and I thought, Look at what this magnificent person is doing with the platform that she has, with her celebrity. I had great regard for her. When your friends and people you consider your family are dying, you have to say something.

Looking back, how would you describe your career?

I guess if I look back at the body of work that I've been so generously given, what stands out is that I've gotten the opportunity to speak out about what’s valuable to me. And I find that at this point in my career, the more I mature, the more I’m getting those opportunities. The fact that that's happening now, more than it ever has before, is kind of striking and stunning to me.

As a performer, you try to tap into something true and authentic. But in some sense, you have to sell parts of yourself as a manufactured product too, like when you do interviews or you’re promoting a project. Do you ever feel like there's a disconnect in that?

I don't separate any of that out. I use myself and that's all I have.

You have two Tonys, two Daytime Emmys, you've been nominated for four Primetime Emmys and a Golden Globe. So you’ve been to a lot of award shows in your career. Does it ever become a grind?

Out of all the television that's being done and all the film that's being done, to be acknowledged in that way is marvelous. I feel that way about my peers as well-I want to acknowledge them. I’m not a Pollyanna about it. It's that I see it as another form of the connection to the work. That's a truth.

I find that when I come to things from that perspective, it shifts everything. It's all about context. The context is: I get to be with my friends. I get to go to a party and celebrate the wonderful work my friends do. I have gone to a lot of awards shows, but when you start holding it up as a grueling job requirement, then it ends up being a task rather than something to be grateful for, something that came out of the work that you did. The award shows are part of it, just like the interviews. If you don't hold it in the context of gratitude, you're going to be miserable all the time, and you're going to make other people around you miserable. That's not how I want my world to be. My choice is to bring my full self and my appreciative self to the work, and to everything that comes with it.

For years, you’ve brought major fashion game-not to mention major red carpet posing game-to award shows.

I have a brilliant stylist, Jack Yeaton, and Jack has an impeccable eye. The people who have dressed me on the carpet, it's my thank-you to them. This is someone's vision. This is what someone took the time to create. It's a walking piece of art. It's live. It's organic. And if people are generous enough to lend me their art, and Jack has the wherewithal to put me together in this way, why not enjoy that? I'm not above it all. I adore it. What, I'm going to go on the red carpet and have an attitude? What use is that? The idea is to bring joy, bring enthusiasm, be that person.

When you landed Who's the Boss?, did you think it would be such a pivotal role for you?

Angela Bower is one of the great lessons of my life. Young women come up to me and say, "I grew up with her, and she showed me that a woman could be the boss." We didn't really know the cultural shift it was creating. I had just come from a soap, and we were a midseason replacement. All I know was that I adored Katherine Helmond [who played Angela's mother Mona Robinson]. I had great respect for her and for her career. She is a living example of how to operate in the business.

You started your career on Broadway in the 1970s. Then you landed One Life to Live, where you met your husband, who convinced you to make the jump to the West Coast and get into television. Though you did some plays after that, the next time you were on a Broadway stage, it was 2010, in Lombardi, about legendary Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi. How did it feel to return to the theater after so long?

After Ugly Betty, which shot in New York, I thought, Oh goodness, what am I going to do? I really wanted to stay in New York longer. Then I got an audition for Lombardi. Several people told me I shouldn't do it, that it was too small a part. I said, excuse me, I haven't been on Broadway in over 30 years. I think I should go in for this. I walk into the room, and I meet this person who is charming, smart, funny. I felt like I had come home. And it was Thomas Kail [who would later direct Hamilton]. I felt comfortable, and we had this wonderful time in the audition. He gave me the job in the room. Then I was nominated for a Tony, which, I think, besides surprising me, surprised a lot of other people-the same people who had said, Why would you want to do this part?

And during the run of Lombardi, my agents called and said Richard Greenberg's people want you to come do a reading. The theater community had welcomed me back in this extraordinary way, and I wanted to keep letting everybody know that I meant it. I wanted to be back. I wanted to be part of the community again. And, please, it's Richard Greenberg. He's an extraordinary writer. So I went in, and Joe Mantello, who I'd never met before, was there. We've also since become friends. I did the reading with all these great people, and I laughed, and I said goodbye. And that was that.

But because Joe had seen me at the reading, he thought I should take over for Linda Lavin in Other Desert Cities. She was leaving to go do The Lyons, Nicky Silver's play on Broadway. So they offered me Other Desert Cities, and I got nominated for a Tony for that role. It was my first win. And then, Lynne Meadow at MTC [the Manhattan Theater Club] commissioned a play from Richard Greenberg, The Assembled Parties, for me and Jessica Hecht. I was nominated for a Tony again, and I won again. And it all came out of Lombardi and the reading for that Richard Greenberg play. Because I said yes. I think it's always a good idea to say yes.

So a lot of it is just showing up and saying yes.

If I'm on my deathbed, I don't want to have any regret. I don't want to think, What was I so afraid of? I mean, you can find a million reasons. But there's a yes in there somewhere. You know intuitively that it's essential for your personal growth to take a chance.

Was that the first time you took a leap like that on stage?

No, I remember in 1999 when I was given the opportunity to take over for Kathleen Chalfant, who was so extraordinary in the [Off-Broadway] play Wit. I was terrified to go back to the theater-I hadn't been on any stage at all in 22 years-but I did it. I had to shave my head. I had to be naked on stage. But knew I had to muster my courage.

When you perform in front of a theater audience, or even in front of a studio audience, you're getting feedback in real time from the audience. How do you find that same energy working in film or on a single-camera show?

My responsibility is to show up, work on the character, and give as much as I can to the people around me. While on stage, you have that give-and-take with an audience. You can still create that when you're on a film set. I try to be as connected as I can be to the people who are on the team, in the room. I don't hold the camera as a separate entity. There are also the people behind those cameras, the focus, the grips, the people who are driving me to work in the morning. There's a whole energetic team, a collaboration. When I was working with the directors Gwyneth Horder-Payton and Dan Minahan on [The Assassination of Gianni Versace], I felt very connected to them. There was one very emotional scene. I could feel everybody. They were present, responsive, there for support. That's what a theater audience is as well. The dynamics are different, the content is different, but the context remains the same: it's all about connection and collaboration.

Let's talk about Transparent's Shelly Pfefferman, who you’re about to play for the last time in the show’s feature-length finale. What drew you to her?

I've always said that Shelly, more than anyone, is so lonely. She wants to connect with people so deeply and desperately, but she has absolutely no idea how to do it, so what she ends up doing is pushing everybody away. She's so fascinating to me. Jill [Soloway, creator of Transparent] and the writers created this context, and all of a sudden out comes this woman. I adore playing her. I will miss not playing her very much.

When you make a connection with another woman in the arts-whether it’s America Ferrera in Ugly Betty or a theater power-producer like Daryl Roth-what lessons are you sharing with other women and what lessons are they sharing with you?

What I learned from America is how to carry myself in the world in ways that keep making a difference. Look at the choices she makes in her career, starting from the very beginning: Real Women Have Curves, and how she took that to Ugly Betty, and now she's doing Superstore. Meanwhile, she's really on the forefront of the #MeToo movement, really championing women, and informing the ways we relate to each other. And what I learned from Daryl is how to pick great material. She has impeccable taste. She knows what will be powerful and potent in the world, what will challenge an audience. Witness the piece that she's doing now, [Gloria: A Life, a play about the life of Gloria Steinem].

The top note is that we're all sharing with each other. There's a different tone to how women are relating to other women now. We are there for each other in ways that I didn't feel before. The edge of competition is out of the equation. Some of the younger women may not have experienced it in the same way, but I experienced it. Now, we're all working together, not only the women who are more mature, but also the women who are young, vibrant, starting out, and embracing all of us who have been around for longer. The world is changing. It is changing.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cinematography by Mario De Armas | Style Editor Tiffany Reid | Style Assistant Sara Lucas | Tailor Lucy Payne | Hair by Stefano Greco at Forward Artists | Makeup by Vincent Oquendo at The Wall Group | Set Design by Amy Henry | Special Thanks to Cavallier Investigations | Video Production by Rachel Liberman | Production by Oona Wally, Suze Lee, & Sameet Sharma

('You Might Also Like',)