Levittown guitarist Danny DeGennaro's life and death told in book by Rutgers law dean | Mullane

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was a tough time for John Farmer. It was 1993 and his wife, Gail, 40, had died suddenly. He was grief struck.

“A very difficult period of my life,” he said.

He took a leave of absence from his job as assistant U.S. Attorney in New Jersey. He took long walks from his home in Lambertville, N.J., crossing the bridge over the Delaware River into New Hope.

“Just trying to process things,” he said.

The town bristled with bars with live music. He walked past The Ringside Pub, and got his life back.

“I heard that guitar, and I will never forget it,” he said.

It was soulful, blues rock.

“I thought it was a recording,” he said.

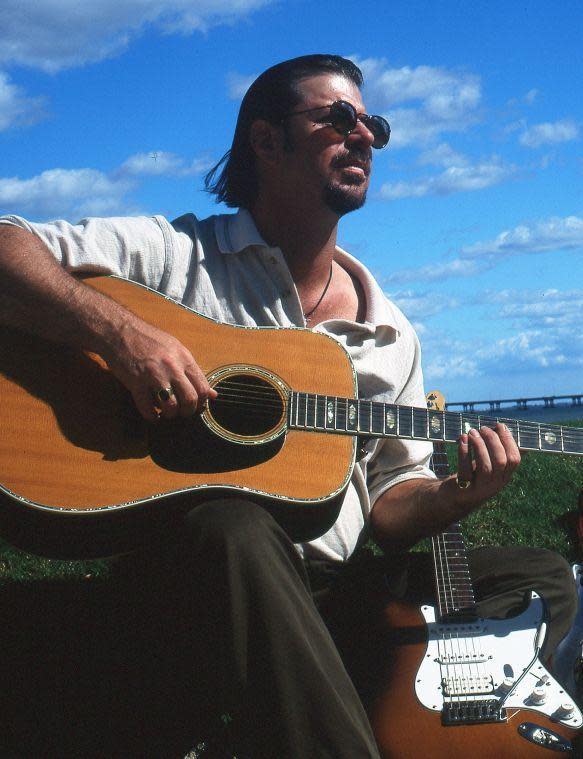

He walked in, no cover charge. On stage was Danny DeGennaro, a guitarist, singer and songwriter from Levittown.

“Danny’s playing, and his voice, it was remarkable. I felt like I was hearing one of the great musicians ever,” he said.

He took a seat. DeGennaro’s music had an instant healing effect that, even today, he can’t quite describe.

“It was the first happy moment I’d had in a while,” he said. “It made me realize that there was still beauty in the world.”

The band had equally talented musicians, like T.J. Tindall, who had been Bonnie Raitt’s guitarist.

Farmer became a regular at the Ringside.

“He woke me up,” he said.

And then the band was gone, no longer appearing at the Ringside.

Years passed. Farmer’s distinguished law career continued. Dean of Rutgers Law School Newark. Attorney General under Gov. Christine Todd Whitman. Even governor of New Jersey for 90 minutes due to a fluke in Jersey state law during a complicated change of leadership.

He remarried. One night he was in New Hope, on his way to the Logan Inn with his wife, Beth, when he heard the music again.

“That guitar was unmistakable. And I said to my wife, ‘That’s the guy!’”

DeGennaro was playing alone, acoustic. He looked as beat up as Route 13 after a hard winter. Farmer approached him.

“I said, I know you won’t remember me, but I saw you at the Ringside Pub. And he said, Ringside? In Florida? No, I said, here in New Hope. He said he thought he remembered it.

“He seemed broken down, and he confirmed that his health was poor. He told me he was trying to restart his career, and that he and T.J. Tindall were trying to get something together.

“I said, look, you really helped me out at a tough time in my life, and if there’s anything I can do for you, I’d be happy to do it,” he said.

Farmer and DeGennaro made plans to get together after Christmas that year, 2011. Farmer texted and left messages, but DeGennaro never responded. In January 2012, he searched online for him.

“A headline came up, ‘Bucks County musician slain.’”

DeGennaro, 56, had been murdered a few days after Christmas when he was ambushed by two men who had conspired with others to rob him at his Levittown home in Crabtree Hollow.

“I was stunned,” Farmer said. “Why did this happen? People say ‘Things happen for a reason.’ No they don’t. This happened for no reason at all. How do you explain his life, the beauty of his music, its effect on people, and then to have all of it snatched away in a moment?”

More on the death of Danny DeGennaroGunmen found guilty of murdering Danny DeGennaro

Farmer, now director of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers, attempts to explain this in his book, “Way Too Fast,” about DeGennaro’s life, to be published April 23.

He interviewed a hundred people, from family to close friends, to the musicians who gigged with Danny, to Bucks Count DA Matt Weintraub, who prosecuted DeGennaro’s killers.

He learned two things. DeGennaro was a child prodigy and his life coincided with the cultural touchstones of the baby boomer era.

“He grew up in Levittown, the iconic American suburb,” Farmer said. “And he loved growing up there. The kids had all this freedom to roam, at the same time they were safe from the world’s troubles.”

Danny got his first guitar in 1964, after the Beatles played the Ed Sullivan Show. He took lessons, but was a natural.

“He was hardwired for music,” he said.

More:Danny DeGennaro Foundation

By 11, he got his first press write-up in the Trenton Times. His father, Jack, a crane operator at U.S. Steel’s Fairless Works in Falls, realized his son’s talent, and worked to cultivate it.

“He saw how people reacted when Danny played,” he said.

Jack DeGennaro formed a band, The Excaliburs, with Fairless co-worker Ronnie Garrison, of Bristol. Danny was lead guitar.

“Here he was at 12, playing in a multi-racial band, in Trenton, Philadelphia, Atlantic City, while cities in America were burning,” Farmer said.

Farmer found that, at that time, the local live rock music scene in Levittown and Lower Bucks County was robust, perfect for an aspiring star.

“It rivaled anything at the Jersey Shore,” he said.

But bad things happened. In 1970, when Danny was 15, he smoked weed for the first time. At 17, he tried heroin.

“That became a lifelong struggle,” Farmer said.

His drug ordeals showed up in his songs, like “Way Too Fast” in which he describes traveling from Levittown to Trenton to meet his dealer:

“Gone to see my man on the edge of town/Got to run the bridge again/Gonna find out, gonna hunt him down/Times I think he’s my best friend.”

And more explicitly in “I Was Not There”: “Ten thousand miles of road dust can’t cover the scars that I’ve put on my arms.”

He graduated from Pennsbury High School in 1973, a time that Farmer describes as the last big wave of hires at the Fairless Works.

“Six years later, all his friends were being laid off, and (Fairless) was shutting down,” he said.

The place that gave so many Levittown kids a solid middle-class life was a ghost. Among those who lost his job at Fairless was Danny’s father, Jack.

DeGennaro’s song “Walk Away” is from the point of view of a laid off Fairless steelworker:

“I’ve been pushed aside, thrown away/Where do I hide when the people say, ‘Walk away.’”

He spent the 1980s and 1990s gigging with bands like Kingfish, writing songs, recording albums and playing with big leaguers like Bo Diddley, Clarence Clemons of the E Street Band, The Hooters, and with members from Blood, Sweat and Tears and Billy Squier's band.

He performed for record producer Clive Davis, but Davis took a pass. The record industry was changing. Signing unproven acts was too risky for record industry bean counters.

“It was at a time when Clive Davis was more interested in stealing successful acts from other labels, rather than investing in new talent,” Farmer said.

Moving to Florida, DeGennaro led the house band for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, but was fired when he got into a fight with a friend of the team’s owner.

“The rest of the band said, ‘You can’t fire Danny — he is the band. You’ve just fired the race horse,’” he said.

So why didn’t Danny DeGennaro make it big?

It wasn’t drugs and it wasn’t lack of talent, Farmer said. It was ambivalence about fame. He was skeptical of a life lived for fame and money. He was reluctant to walk away from everything and everyone he knew and loved in Bucks County.

“He loved Levittown, but he also hated it," Farmer said. "He’d go away for a long time, but he always came back home, to the people he loved. He loved his friends. He really loved his parents.”

DeGennaro spent the last decade of his life caring for his mother and father.

“Lots of great art is made in these kinds of unresolved conflicts that people have within themselves. And that was his conflict," Farmer said. “T.J. Tindall told me that you can’t evaluate Danny on terms that weren’t his terms. Being famous and having lots of money is not what got him up in the morning. He wasn’t like Madonna or Mick Jagger.”

DeGennaro liked being a Levittown guy who never charged anyone a cover to see him play.

“He loved playing music for his friends," he said, "and he did it on his terms, and it was great music.”

MullaneFor Levittown's 70th, a quirky museum of odd artifacts

WhodunitCan DNA solve a little girl's 1962 murder?

Columnist JD Mullane can be reached at 215-945-5745 or at jmullane@couriertimes.com.

This article originally appeared on Bucks County Courier Times: Danny DeGennaro's life chronicled in book by former NJ Attorney General