Lexington’s intentional segregation took years to create. It will be hard to unravel. | Opinion

The two of us began reading and learning about the roots of Lexington’s residential segregation three years ago. Our motivation was simple: we were tired of being bystanders who benefit from race-based inequality in our city.

We learned that 20th-century residential segregation underpins many current differences in wealth and financial well-being between Black families and white ones. The typical Black American family has 12 cents in wealth for every $1 of white family wealth. This gap has not changed in 70 years, and accounts for life-defining differences in health, education, political power and employment.

We are in an early stage of learning. As part of the 2023 city-wide focus on segregation, we will share three insights.

Residential segregation in Lexington was intentional.

Government laws and policies, as well as private-sector practices, protected and subsidized White house-based wealth-building in many ways while actively hindering Black wealth-building. We focus here on three tactics.

▪ Race-based deed restrictions. Many White Lexington families lived in neighborhoods where racial deed restrictions ensured White owners could not sell or lease their homes to African Americans. Our research so far has only scratched the surface, but we found restrictive covenants in every pre-1949 Lexington neighborhood we studied. Participating neighborhoods include such familiar places as Kenwick, Goodrich and Meadowthorpe.

▪ Redlining. Beginning in the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), originally a New Deal program, used racist criteria known as “redlining” to allow white people to get low interest, long term home mortgages, while preventing Black homebuyers from doing the same. This provided a huge economic benefit to white homebuyers during a crucial period in our country’s financial history. Thousands of white families were able to enter the housing market for the first time. They began building equity that gradually became generational wealth. Redlining denied most African American families those same opportunities.

▪ Race-based steering by realtors. It was common— and legal for decades — for realtors to show White homebuyers homes only in areas where whites already lived; Black homebuyers often could not even learn what houses were for sale in White neighborhoods.

Segregation’s harms continue.

By 1968 the Supreme Court and Congress had eliminated the most obvious laws and policies that promoted segregation. But segregation lives on in Lexington, actually increasing between 2010–2017.

In the United States, home ownership and wealth are interwoven. African Americans in Lexington own their own homes at less than half the rate of white home ownership (31 percent to 65 percent).

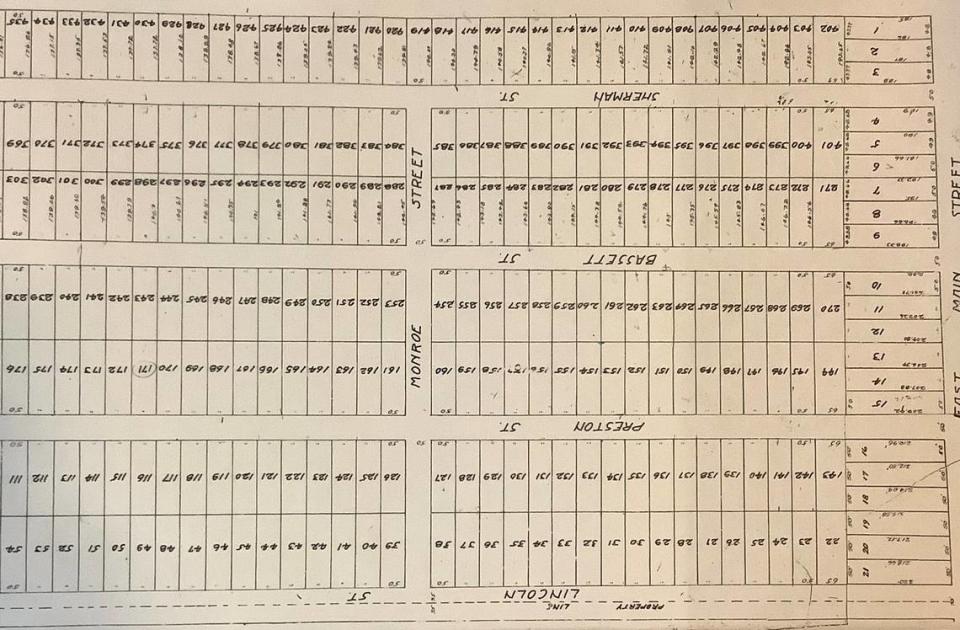

In the 15 years of rapid suburban expansion following World War II, Lexington builders and developers offered 15,546 suburban lots for development. Of those, African American families had access to 225 in two small subdivisions.

Some African Americans have overcome these hindrances to succeed financially, live where they choose, and flourish. And many who lived in legally segregated neighborhoods as children say they miss the tight connections, mutual care and shared sense of community from that time.

In “South to America,” scholar Imani Perry says, “One of the difficult side effects of desegregation — and you’ll hear it again and again from Black people who lived in the before time — is that something precious escaped through society’s open doors.” Black people exited legal segregation, she says, only to experience “the persistence of American racism alongside the loss of the tight-knit Black world.”

That American racism, codified in Lexington’s past segregationist policies, meant that developing house-based wealth remained out of reach for most African Americans from roughly 1900–1970.

Using government and financial power, white people designed segregation. We can undesign it.

In the follow-up to “The Color of Law,” Richard Rothstein and Leah Rothstein wrote “Just Action,” which suggests zoning reform as one path to undoing segregation’s harms. Certain zoning changes could make it easier for African Americans to buy homes that build family wealth. For example, zoning reforms could allow a greater variety of home types and sizes in previously single-family-only zones.

Considering zoning changes as one path toward equity would mean asking ourselves to think carefully about our positions on sensitive issues like density and homogeneous housing types.

African American wealth-building boosts families and the entire community. It is our hope that when we as a community recognize how intentional segregation kept Black families from building wealth, many of us will choose to work together to repair that injustice.

Rona Roberts is a writer and organization development adviser. Barbara Sutherland is a retired city employee and librarian. Together, they are the creators of SegregatedLexington.com.

Lexington has recognized its housing segregation. Now it has to come up with solutions. | Opinion

Lexington’s segregation sits on a historical scaffold of white supremacy | Opinion

‘The Color of Law’ unveiled truths that Black Americans have always known | Opinion

We’ve ripped the scab off Lexington’s hidden housing injustice. What comes next? | Opinion