Lexington’s Narco Farm did groundbreaking addiction research. We’re still learning from it

The Federal Medical Center in Lexington has a fairly simple purpose — it’s a facility used to treat seriously ill people who are imprisoned by the federal government.

Its intended use when it opened in May 1935 was far different: the 12,000 square foot government facility constructed in Fayette County, and known at the time as the Narcotic Farm, was America’s first drug rehab facility. The facility that now houses nearly 1,300 male and female offenders was a place for researching how drugs affect humans. It was the first facility of its kind to implement rehab treatment efforts.

The Narcotic Farm, also informally known as Narco, was operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons and the Department of Public Health. A second, smaller facility opened in Forth Worth, Texas. Both eventually offered a space for the United States to be innovative in its approach to drug addiction through treatment and research.

It also became a place for the government to give drugs to people, including LSD, during experiments performed for the CIA. Then the war on drugs made addiction a criminal issue, not a medical one. More than 80 years after the facility opened, the U.S. still grapples with issues it thought the Narco Farm would solve.

Work at the Narco Farm attempted to uncover a question experts grapple with today: is substance use disorder – a common medical term for drug addiction – a criminal issue, a mental health issue, or a social issue?

As previous Narco patient David Dietch said in the Narcotic Farm documentary, an hour-long feature on the facility, the Narcotic Farm was a prison and a hospital, but it was also a symbolic and literal expression of America’s faulty perceptions about how to treat addiction.

Authors of a book on the Narcotic Farm offered a mixed review of how the facility changed America’s approach to drug addiction.

“Despite its best attempts, Narco was unable to make significant changes in addicts’ abilities to stay off drugs. But to judge the institution solely by its relapse rate — or its controversial research — minimizes its real accomplishments. Many treatment methods still in use today were pioneered there, most notably methadone assisted-detoxification, and the research staff made deep inroads into understanding the psychological and neurological factors that can lead to drug dependency,” authors of “The Narcotic Farm” wrote in the book, which was published in 2008.

Striking parallels exist between historical responses and contemporary insights, primarily stemming from issues of stigma, legislative measures, studies on psychedelics and the plea of sustained community support for people recovering from addiction.

Rehabilitation vs. incarceration: Finding the balance

In 1935, researchers and medical professionals recognized substance use disorder as a chronic relapsing disease, not a moral failing. In fact, one of the research facility’s first discoveries was that people using drugs were not “degenerates’‘ or “criminals,” despite societal stigma.

A 1939 full page article by the Denver Post about Narco highlighted how the perception of addiction was changing in the U.S.

“A few scant years ago, dope addicts were treated as criminals, and thrown into penitentiaries, jails and county lockups along with burglars, felons and murderers,” the article read. “Today, this inhumane treatment is slated for discard, for Uncle Sam has come to the decision that drug addicts are not criminals – they are sick people, both mentally and physically – and if given proper understanding and treatment, stand a fair chance of getting on their feet and returning to the world to live normal lives.”

Even Lawrence Kolb Sr., the chief medical officer at Narco, believed in his early work there were “normal” users — prescribed opiates by doctors — and “vicious users,” who acquired their drugs through illicit means. He would later change his mind when he found that nearly 15% of drug-addicted patients were health care professionals, housewives and people who just had access to opioids.

In 2023, efforts to change the perception of substance use disorder are still ongoing close to where the Narcotic Farm was located.

“I think the drug epidemic – which I am going to call it a behavioral health epidemic – has evolved from when I started really not knowing that much to not thinking there was a drug problem to now thinking that there is a behavioral health issue,” said Madison County Judge-Executive Reagan Taylor.

The Madison County jailer, Steve Tussey, told the Herald-Leader previously about 80% of his inmates at the Madison County jail are facing drug-related charges, and are contributing to a recidivism rate of 60%.

Tussey now acknowledges that incarceration is not the answer to what he says is “absolutely a health care issue.”

“It began as a choice and a drug issue, but once they are hooked, it is a health care issue,” Tussey said. “They have a sickness and we need to treat that sickness. The brain is now telling them to do drugs just like our brain tells us to eat.”

The Madison County Detention Center is a local Kentucky facility that has faced chronic problems of overcrowding because of drug arrests and rearrests. The jail has implemented recovery support and mental health treatment despite those options not being a requirement.

This bears a striking resemblance to the concept that the Narcotic Farm was established to capitalize on — pairing rehabilitation with incarceration in the hopes of reforming people with a drug problem to become functioning citizens.

In Narco’s decades of operation, workers and medical staff inside the facility recognized there wasn’t a one-size-fits-all solution to rehabilitating users. Today, 44% of inmates housed in federal prisons are there for drug-related charges, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

“The idea was that being away from drugs, getting healthy, getting some insight and learning skills would result in patients staying away from drugs after they left the institution. But, addiction is a chronic problem. It is very hard to get out of. And it is not going to go away overnight,” said American psychiatrist Robert DuPont in the Narcotic Farm documentary, which released in 2008.

Impact of Legislation: Then and Now

Legislation passed after the Narco Farm opened allowed patients facing incarceration to voluntarily seek reprieve at the facility. Laws passed in the U.S. today present a myriad of methods to address addiction, with attempts to promote both incarceration and rehabilitation.

The Narcotic Addict Rehabilitation Act, passed by former President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966, changed Narco from a prison to a treatment hospital for people facing federal drug charges. They could avoid prison time by volunteering to go to Lexington.

Between 1968 and 1973, those who qualified could serve six months of civil commitment for drug treatment instead of jail. In most cases, young people facing drug charges could have their record expunged if they went to treatment.

In 2022, a strikingly similar measure was introduced by Rep. Whitney Westerfield (R-Crofton) through Senate Bill 90, which aims to reduce incarceration by implementing an 11-county, four-year pilot “conditional dismissal” program that diverts people with mental health and substance use issues who qualify based on medical assessments by providing support and services in the community.

It passed with near-unanimous support, and was signed into law by Gov. Andy Beshear in April 2022.

Defendants can receive treatment for a behavioral health disorder instead of going to jail. With an agreement between the defendant and prosecutors, their charges are dismissed if they complete the treatment program. The option is only available to defendants charged with crimes less than or equal to certain Class D felonies. They also can’t have a previous conviction for a higher felony, or be charged with violent offenses or sex offenses.

Before the war on drugs, laws like the Narcotics Control Act of 1956 imposed harsh penalties, setting a precedent for draconian measures. Despite recent efforts, a 2022 report by the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy revealed the Kentucky General Assembly has often passed bills increasing penalties rather than reducing them, reflecting a historical trend of prioritizing incarceration over rehabilitation in drug-related legislation.

The Kentucky Center for Economic Policy wrote in its report that House Bill 215 and Senate Bill 179 – passed in the same session as Senate Bill 90 – were “particularly concerning” because of the potential number of people the laws could put behind bars and keep there for longer periods of time.

HB 215, a bill relating to drug trafficking, increases existing penalties by requiring any individual convicted of aggravated trafficking or importing of carfentanil, fentanyl or fentanyl derivatives to serve at least 85% of their sentence before being eligible for release.

Before this change, those convicted were required to serve at least 50% of their sentence. The bill also prohibits pretrial diversion for anyone charged with one of these offenses. Language in the bill left policy experts confused on how the law would be interpreted. Many feared that anyone caught with any amount of these substances would be jailed instead of targeting the “drug king pins” it was allegedly designed to target.

The bill’s sponsor, Bill Wesley (R-KY) said, “(Drug traffickers) better think twice before dealing in Kentucky. They will get their act together in prison, and jail, and they aren’t going to get let go just because we are overpopulated.”

Studies into drug use, opioid agonists and LSD

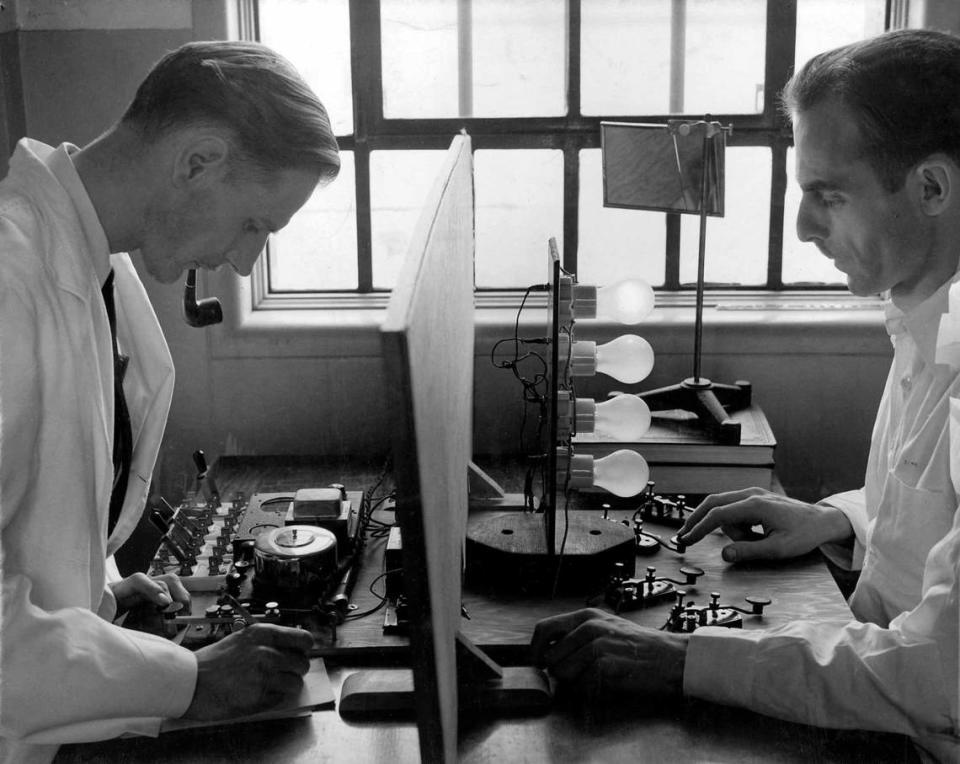

Apart from a new approach to treating addiction, the Narcotic Farm also carried out federally-funded studies examining the effects of drugs on humans and the experiences of withdrawal.

In 1948, Narco (later named the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital) opened the Addiction Research Center when Congress called for the program. That program included giving federal inmates an array of drugs in order to study changes as they went through intoxication, dependence and withdrawal.

The center recruited male prisoners who were “highly experienced and knowledgeable drug addicts” to be tested. At the time, the ARC was the only laboratory in the world that had access to a captive population that could be used as testing subjects, according to the book “The Narcotic Farm,” written by Nancy Campbell, JP Olsen, and Luke Walden.

Heroin, cocaine, marijuana, barbiturates, LSD, morphine and other pharmaceuticals were among the drugs tested on the inmates.

“Researchers studying hardcore drug addicts found that, fundamentally, they were ordinary people, not the ‘degenerates’ they’d often been portrayed to be,” according to “The Narcotic Farm.”

Sidney Louis was a nurse supervisor commissioned to work at the Lexington treatment facility for 10 years and the Fort Worth location for four years. As one of the last living employees of the facility, he said the treatments explored there were new territory.

“Much of what is known today about how the brain reacts to various drugs can probably be traced back to the pioneer efforts of the devoted scientists at this laboratory,” Louis told the Herald-Leader. Louis saved hundreds of the facilities’ artifacts and donated an entire collection to the Kentucky Historical Society.

The Addiction Research Center was the epicenter of research conducted on methadone, a long-acting full opioid agonist, and a schedule II controlled medication which is used commonly today to treat individuals with opioid use disorder. A 2022 study by Noa Krawczyk noted in 2019, 26,265 people who were given buprenorphine and 4,782 were given medication at an opioid treatment program, which largely consisted of methadone.

In several recent rulings, Kentucky prisons and jails have settled lawsuits in which they were accused of violating the Americans With Disabilities Act by not offering medications for opioid use disorder.

Before the Cold War, the CIA was secretly paying the facility to study the effects of LSD in attempts to distinguish if it could be used as a militant investigative tool against Russian spies. After World War II, the Addiction Research Center tested drug effects of pharmaceuticals developed on the market and the potential for its abuse.

In 2022, Kentucky officials attempted to head an initiative to become a pilot state for psychedelic studies focused on treating substance use disorder.

Recently, the former chair of the state’s Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission who oversaw opioid lawsuit settlement funds proposed allocating a portion of the almost $900 million in funds for research on ibogaine, an experimental drug derived from the root bark of an iboga shrub native to West Central Africa.

Although ibogaine is classified as a Schedule 1 drug in the U.S. and lacks FDA approval, it has gained international attention for its potential therapeutic effects on opioid addiction. However, the drug’s use has raised concerns due to severe, even fatal, side effects observed in some patients, particularly related to its impact on the heart.

While the proposal was thought to have support in moving forward, new Attorney General Russell Coleman appointed a new advisory chair, effectively terminating the ibogaine proposal in 2024.

The war on drugs creates relapse for society’s views of drug users

In June 1971, President Richard Nixon officially announced drugs were “public enemy number one,” launching his administration’s war on drugs. He called on Congress to give a minimum of $350 million to fund the war. Just two years before, the nation’s federal drug budget was $81 million, according to “The Fix,” by Michael Messing.

At the time he declared this new War, less than 2% of the American public viewed drugs as the most important issue facing the nation, according to a study published in the University of Chicago Press Journals.

Nixon, followed by President Ronald Reagan, went on the media offensive to sensationalize the emergence of crack cocaine in inner-city neighborhoods — communities devastated by deindustrialization and unemployment — suffering from economic collapse.

In August 1989, President George Bush Sr. characterized drug use as the “most pressing problem facing the nation,” according to “The New Jim Crow.” Shortly thereafter, a New York Times/CBS News Poll reported that 64% of those polled – the highest percentage ever recorded – now thought that drugs were the most significant problem in the United States.

Despite medical research done at the Addiction Research Center and Narco, the federal government chose to redirect their approach to incarcerate their way through America’s drug problem — and funneled billions into reverting towards a method they knew did not work.

Between 1980 and 1984, the FBI anti drug funding increased from $8 million to $95 million. Department of Defense antidrug allocations increased from $33 million in 1981 to just over $1 million in 1991, according to the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy.

By contrast, funding for agencies responsible for drug treatment, prevention, and education was dramatically reduced. The budget of the National Institute on Drug Abuse was reduced from $274 million to $57 million from 1981 to 1984, and anti drug funds allocated to the Department of Education were cut from $14 million to $3 million, according to the US Office of the National Drug Control Policy, National Drug Control Strategy.

The war on drugs and the hysteria it was founded upon continue to construe substance use disorder as a criminal issue.

Job training and community support

With criminal charges in abundance as a result, the American economy suffered with a reduction in the work force. Illicit drug use accounted for $49 billion in reduced participation in the workforce, according to the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Prescription opioid misuse alone accounted for an estimated $7.9 billion in lost employment or reduced compensation, according to the same study.

Many who have gone through recovery have said when they reach sobriety, reentering society is a beast to tackle, because they have a felony conviction often associated with criminal drug charges. A log of their criminal history has previously made it close to impossible to gain willful employment.

The survey indicated people who are employed compared to those unemployed are more likely to demonstrate lower rates of recurrence, higher rates of abstinence, less criminal activity, fewer parole violations, improvements in quality of life, and a more successful transition from long-term residential treatment back to the community.

Even in the early 1940s, researchers at the center stressed that without society’s help, those in recovery would not succeed and said improved cooperation from communities in employing people in recovery would strengthen their results.

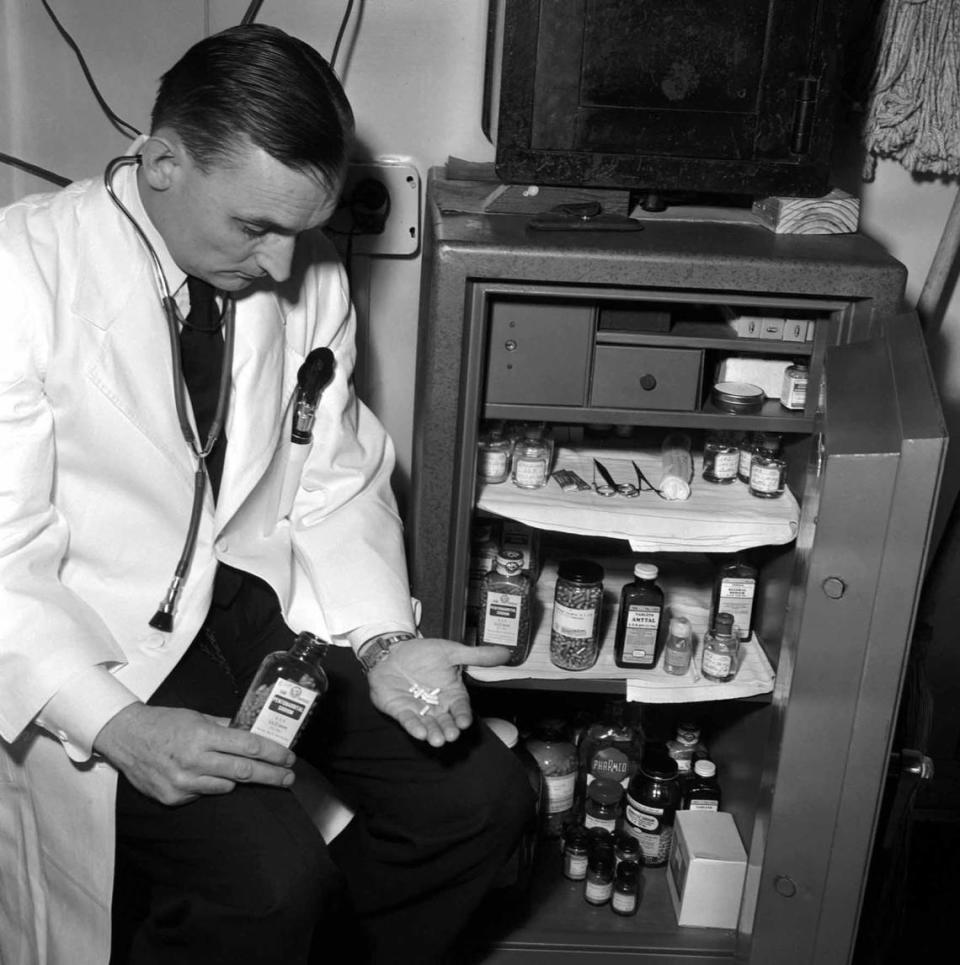

The Narcotic Farm and those who oversaw it thought the work was the therapy the patients needed. There, male patients worked as apprentices for X-ray technicians, mechanics, electricians, dental hygienists, cabinet makers and other tradesman. Female patients worked in the facility’s kitchen or honed their beauty parlor skills.

“An opportunity to earn a decent living is essential for rehabilitation,” a 1940s silent, black-and-white presentation by Dr. J.D. Reichard read. “Relapse to drugs should receive treatment, not punishment. Narcotic addicts can be rehabilitated but only with society’s full cooperation.”

Louis wrote the largest contributing factor to the facility’s relapse rate was because there was a lack of community support. He said state and local authorities thought they could send inmates with drug problems to the federal facilities and “wash their hands clean” of the problem.

“And that was the major flaw in treatment: the local governments saw no responsibility for continued care and support of the former addict when he returned home,” Louis wrote. “Left on his own, often still shaky and uncertain about his freedom from drug dependence, and back in the same environment from which he came, the individual would too many times relapse and fall back into his old behavior and lifestyle.

“Had there been strong support when they returned home, many more would have made their way to successful, drug free lives.”

In recent years, the U.S. has still grappled with how to properly encourage re-entry for previous drug offenders.

Kentucky has made strides in efforts to help people recovering from addiction find jobs. In 2017, then Gov. Matt Bevin implemented the state’s Fair Chance Employment Initiative. As part of this, Kentucky joined 33 other states which “banned the box,” or eliminated the question of whether an applicant has been convicted of a felony from employment applications for certain jobs at the state level.

Rob Perez is the owner of DV8 Kitchen, a second chance employment restaurant in Lexington, which exclusively hires people in recovery. Even Perez, who is surrounded by previous drug users, said he had no idea of what it was like to try and re-enter society after serving prison time, or even completing a treatment program.

He has hosted community re-entry simulations to ask business owners how they can help eliminate barriers for people with prior drug-related felonies.

“We want this event to pose the question to the bluegrass region that if you have housing or have jobs – it’s fine if you have to have a barrier – I understand that, but can you find something you can say yes to?” Perez said previously.

How Narco ‘failed’

The book and documentary featuring the facility claimed Narco and the ARC contributed to their own failure when it became known that researchers were purposely re-addicting people who came there to recover. A set of Congressional hearings was conducted, and the government questioned the ethics of the testing.

The public had major ethical concerns about how the testing was done, and the program was ultimately deemed a failure. A relapse rate for patients was recorded at 90% when the facility closed in the 1970s, according to facility presentations stored at the historical society.

Narco was labeled as the “de facto university” to learn about drug use. Patients often left the institution with a better understanding of drugs — and how to get them.

Patients learned how to get by during drug shortages, manipulating doctors for supply, finding out which users were informants and finding out who in the facility was a good connection for substances.

Bob Morgan, a Lexington native, artist, and gay activist, was on the scene when Narco was at its height. He attended some film showings at the facility, and later met with the former patient and author William Burroughs Sr. According to Morgan, the Narcotic Farm brought a community of sophisticated drug users into the city limits.

He recalled people he knew people that rented houses near the facility on Leestown Road and dealt drugs to patients at Narco who had weekend passes.

“Now a lot of people that I knew that were associated with Narco never got clean, and they added to the ... using community,” Morgan said. “People who got clean, added to the community and the clean community. But basically, we had a much more sophisticated drug using community as well as a recovering community because of this association.”

The public also took issue with researchers being accused of compensating drug study participants with more drugs. Participants could receive time reduced from their sentence, or receive drugs that could be put in “the bank” for future use at their disposal.

The ARC was later established as the National Institute on Drug Abuse and despite a perceived unsavory demise, is still recognized for its research efforts into drug addiction.

Louis insists that Narco didn’t fail. He contends the facility fulfilled its purpose, which prompted its closure.

The primary reason for the two federal facilities’ closures, Louis said, was because they had done their job so well: to educate local and state governments on how to operate their own drug treatment programs.

In high levels of government, there was a belief that states failed to assume their share of responsibility for treatment of their addicted citizens, according to Louis. So the federal government stopped providing treatment and needed the state and local governments to face a problem they’d dodged for decades.

“How many of that ‘90%’ that relapsed were able to free themselves from the drug habit after their second, third, perhaps fourth, admittance to the Lexington program?” Louis wrote. “So many brave, determined, souls straightened out their lives on their own without the support of state or local governments. They had to.”

Authors of “The Narcotic Farm” wrote that a near impossible dream grips the public imagination — that the United States will become a “drug-free” nation. But perhaps, they wrote, “more sensible views will prevail — that relapse is the norm; that drug addiction should be treated as a chronic, relapsing problem that affects public health; and that meeting people’s basic needs will dampen their enthusiasm for drugs.”

“Until then, effective drug policy will prove as elusive a quest as the impossible dreams that built the Narcotic Farm,” the authors wrote.