Lexington has recognized its housing segregation. Now it has to come up with solutions. | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s never too late to do better.

Lexington is in the middle of some important conversations about its shameful history of housing segregation. That it happened in nearly every city in America makes it no less shameful; it only lays bare exactly how determined white people were to keep Black people in subservient roles in every aspect of our society.

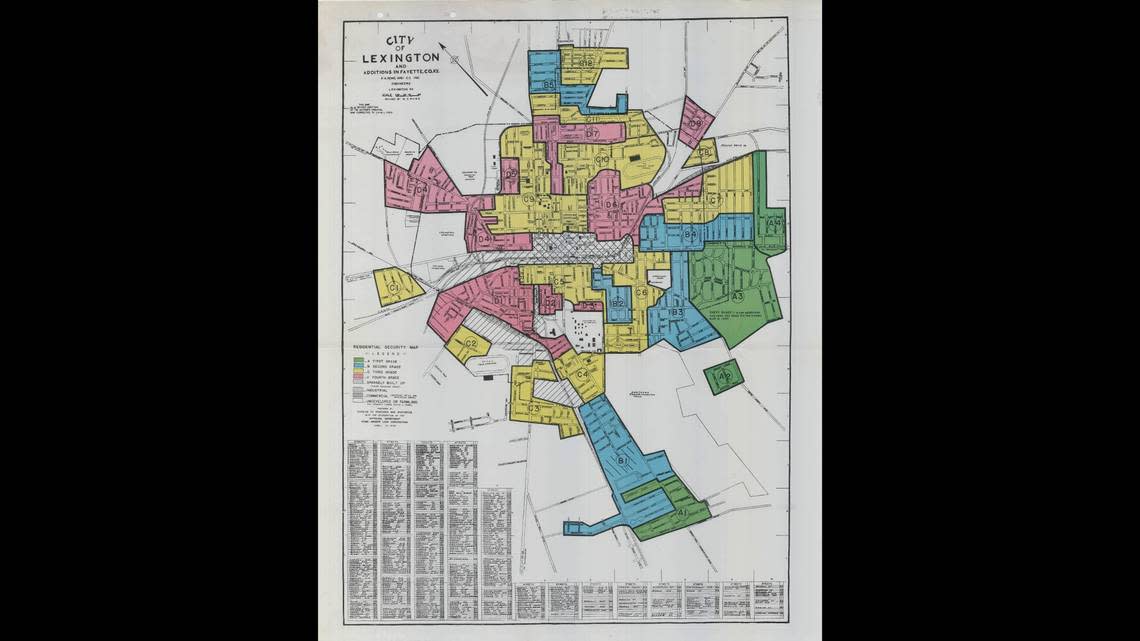

From racially restricted house deeds created by the developers of neighborhoods such as Kenwick and Meadowthorpe at the turn of the century to the redlining of neighborhoods by federal housing agencies to urban renewal in the 1970s, the odds were stacked against Black people owning homes.

That, in turn, stacked the odds against the creation of generational wealth, a gap that exists to this day. Gentrification of Black neighborhoods further compounds these problems.

Lexington is lucky, however, to have some people and organizations who are willing to squarely face these past wrongs. First off, two senior citizens have created a website titled Segregated Lexington, which goes deep into the historical records to explain the birth of our divided lines.

Right now, the Lexington Public Library- Central Branch features the exhibit Undesign the Red Line, which explores redlining in Lexington and across the country.

And on Tuesday, the Blue Grass Community Foundation will present Richard Rothstein and his daughter, Leah Rothstein in a talk at the University of Kentucky. Richard Rothstein is the author of “The Color of Law,” the seminal text on federal redlining efforts across the country, which has been our most recent community read.

And together with Leah Rothstein, they produced a follow-up titled “Just Action: How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law,” which examines ways in which communities can fix the problems these policies caused. KET’s Renee Shaw will hold a conversation with Leah Rothstein and Richard Rothstein (via satellite) followed by a brief Q&A session.

The event is free and open to the public, but you must reserve a ticket.

This follows the 2022 event sponsored by the foundation featuring Heather McGhee, the author of “The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together.”

The Rothstein event seemed like a natural fit in Lexington’s evolving sense of its past, Adkins said.

“At Blue Grass Community Foundation, we want a community where everyone can thrive,” she said. “Racial segregation in Lexington, and across the country, was intentionally structured and institutionalized. By understanding our history, we can make the choice as individuals, and as a community, to use this same intention to work towards undoing the legacy of segregation in Lexington.”

Last year, the Herald-Leader asked community members to reflect on “The Sum of Us” in a themed Opinion section. This time around, scholars, activists and others have written about their perspectives on “The Color of Law” and its many overlapping issues.

For example, Anastasia Curwood, a UK history professor and director of the Commonwealth Institute on Black Studies, writes about how white supremacy underpinned the legal manuevers that deprived Black people of home ownership and thus, generational wealth.

Realtor Kristen LaRue Bond reflects on how her profession contributed to the kind of race-based steering that kept Black families out of white neighborhoods, and what they are doing to change that.

Council member James Brown has focused on how a ban on source of income discrimination could change the affordable housing policies that still harm too many poor and minority residents. Rona Roberts and Barbara Sutherland — the creators of the Segregated Lexington website — explore some other possible solutions presented in “Just Action,” such as how zoning reforms could make neighborhoods more accessible and equitable.

These issues are difficult to unravel, but as Roberts and Sutherland write: “African American wealth-building boosts families and the entire community. It is our hope that when we as a community recognize how intentional segregation kept Black families from building wealth, many of us will choose to work together to repair that injustice.”

Lexington’s segregation sits on a historical scaffold of white supremacy | Opinion

‘The Color of Law’ unveiled truths that Black Americans have always known | Opinion

We’ve ripped the scab off Lexington’s hidden housing injustice. What comes next? | Opinion

Lexington’s intentional segregation took years to create. It will be hard to unravel. | Opinion