LGBTQ books are being banned from schools. Here's how kids can still read them.

Earlier this year, the Brooklyn Public Library decided to give teens anywhere in the United States access to its collection of hundreds of thousands of e-books. Schools in some parts of the country were banning many books about people of color or LGBTQ stories, and the library’s leaders felt it was the least they could do.

The vision for the initiative was “that it would be somewhat small, maybe slightly more intimate but transactional,” said Leigh Hurwitz, a librarian who works with the system’s teen patrons and has helped coordinate its LGBTQ programming. “The response was so much larger and more overwhelming than any of us expected.”

Thousands of people from all 50 states and Washington, D.C., have reached out to the library asking for the special "Books Unbanned" e-card in the two months since the initiative’s launch. As of late June, more than 4,000 cards have been given out to youth ages 13 through 21. In May alone, young people using these cards checked out nearly 6,300 books.

The Brooklyn Public Library is part of the growing countermovement of community members and nonprofits working to give children access to banned books, many of them featuring LGBTQ themes.

“We’re seeing a lot of wonderful efforts at the ground level,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association's Office for Intellectual Freedom. “While people may feel powerless, there are ways to help and to still access these books.”

In 2021, the American Library Association recorded 729 challenges to books, the highest number the organization has seen since it began recording such data in 2000. Those challenges targeted a total of 1,597 titles.

And according to a recent analysis by PEN America, literature about LGBTQ themes or characters account for one in three of the titles restricted by districts this past school year.

Proponents of the book challenges say such restrictions are necessary to protect children from exposure to obscene, explicit material.

"A growing number of parents of Texas students are becoming increasingly alarmed about some of the books and other content found in public school libraries that are extremely inappropriate in the public education system," wrote Gov. Greg Abbott in a letter last November to the state's school board association asking it to review schools' book collections and remove titles deemed unfit. "The most flagrant examples include clearly pornographic images and substance that have no place in the Texas public education system."

But their opponents claim such efforts are part of a coordinated, ideological attempt to erase certain perspectives from classrooms. George M. Johnson, author of "All Boys Aren't Blue," has described the wave as conservatives' "crusade to remove LGBTQ+ education from schools."

And accessing that education -- in part through reading queer literature -- can be “a matter of life and death in a lot of cases," Hurwitz said.

In their exchanges with the Brooklyn librarians, teens and their advocates – parents, educators, local librarians – have shared “really horrific or painful stories,” Hurwitz said. Many of those stories have come from LGBTQ youth and their allies who live in areas where queer identities and literature aren’t accepted.

“I was blown away by how many … people in the community are really wanting to make sure that their teens are being seen and reflected in the books they have access to,” Hurwitz said. “The narrative is never about the adults who are doing things like this – it’s always about the adults who are coming to school board meetings trying to have books yanked from the library.”

Books are being removed from schools: Many feature LGBTQ+ characters.

Physical books, physical spaces

More than a fifth of Gen Zers identify as LGBTQ. Yet stories representing those students account for a “miniscule” percentage of the often tens of thousands of books comprising a school’s library, according to Carolyn Foote, co-founder of FReadom Fighters, a semi-anonymous group of current and former school librarians in Texas that formed late last year in response to the growing number of book challenges in their state and across the country.

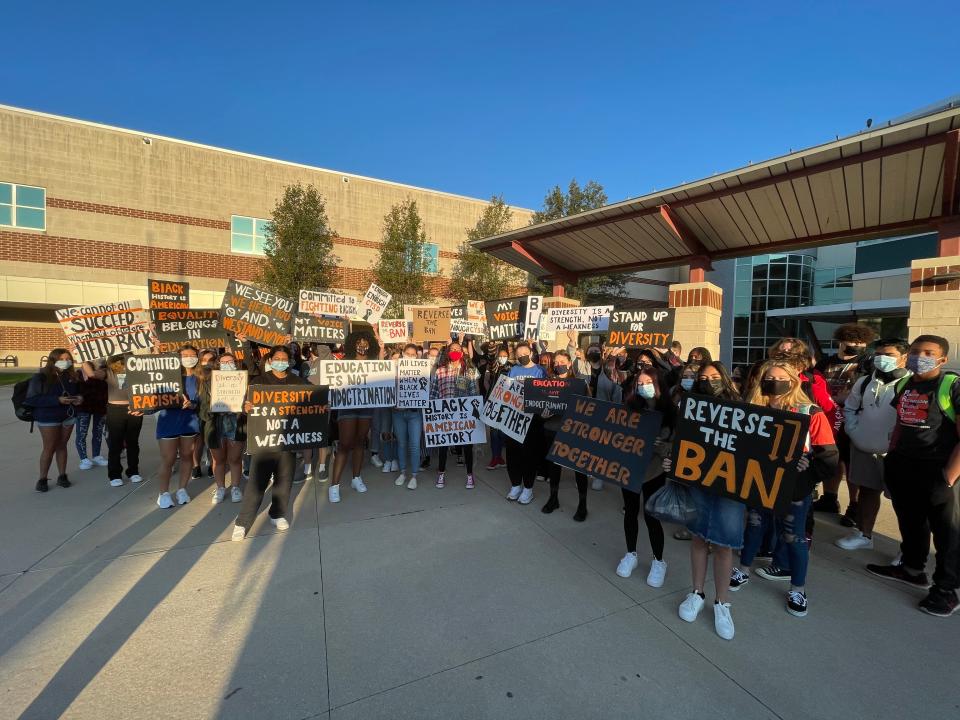

Youth activists and their adult co-conspirators in some parts of the United States organized drives to get physical copies of oft-targeted books into their peers' hands.

In Katy, Texas, then-senior Cameron Samuels found a spreadsheet earlier this year compiled confidentially by their school district listing books banned for various grade levels. Most of the titles dealt with racism and/or LGBTQ themes.

Samuels and their peers at districts across the state partnered in February with Voters of Tomorrow, a Gen Z-oriented civic engagement organization that's helped activists source and distribute copies of Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” and Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” -- two frequently banned books -- at or near school campuses. With the help of donations, Katy students also distributed copies of commonly blacklisted LGBTQ-themed books, such as Mike Curato's graphic novel "Flamer" and "Cinderella Is Dead" by Young Adult novelist Kalynn Bayron.

"We felt like the best way to respond to that would be to organize a book distribution," Samuels said.

In May, Voters of Tomorrow organizers in Florida decided to do something similar after the passage in March of what critics dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law, which bans instruction or discussion about LGBTQ issues among children in the third grade and younger. The Florida volunteers distributed about 150 copies each of “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” “The Bluest Eye” and “The Handmaid’s Tale” – books relating to gender and sexual orientation that have been banned by many school districts.

“Having young people distributing banned books to other young people itself is a very big symbol,” said Santiago Mayer, 20, Voters of Tomorrow’s founder. "Students turn to these titles as educational resources because they’re obviously not getting them in school anymore.”

Other organizations have focused on ensuring educators have access to LGBTQ-inclusive materials at a time when many school districts and library systems are self-censoring out of fear of retaliation. Hope in a Box, for example, curates books and accompanying curricula for teachers and also offers training and mentorship opportunities.

“Many of these educators are the only ones driving this work in their communities, and it can feel like a lonely fight,” said Joe English, founder and executive director of Hope in a Box, a nonprofit that focuses on schools in rural communities.

Pride and Less Prejudice engages in similar outreach and provides LGBTQ-inclusive books, as well as teaching guides, workshops and author read-aloud events to educators in pre-K to third-grade classrooms. Its founder, Lisa Forman, said demand has grown significantly in the past few months. These days, the organization, which started in November 2019, receives several hundred requests monthly from teachers seeking donations.

The sacrifices of prior generations: Why so many Gen Zers identify as LGBTQ

New laws: Some teachers worry supporting LGBTQ students will get them sued or fired

In St. Louis, Missouri, the Black-owned bookstore EyeSeeMe has partnered with Heather Fleming, a local former educator, to provide banned books to teachers, parents and students nationwide each month. People can sign up to receive the books on the organization’s website.

The idea came about earlier this year when Fleming, who used to teach English to high schoolers, noticed that one book challenge after another focused on titles that were her favorites to teach -- and her students' favorites to read.

The program has raised $30,000 so far and has distributed about 1,200 books. Leftover copies of the books will be available at EyeSeeMe for anyone to pick up.

Some independent bookstores, meanwhile, have offered up their spaces for student-led banned book clubs and other efforts aimed at improving queer children's access to literature.

King’s Books in Tacoma, Washington, for example, facilitates a youth and young adult reading group that calls itself “the Queerest Book Club Ever.” Titles discussed at the group’s past monthly gatherings include controversial titles such as “Gender Queer: A Memoir," Malinda Lo's "Huntress" and "Last Night at the Telegraph Club" and Alex Gino's "George."

The book club is "an act of defiance ... it's refusing to be erased. It represents the reality of a population that exists today and has always existed," said Lisa Keating, a Tacoma school board member and advocate for LGBTQ youth whose teen trans daughter, Stella, started the group five years ago. "It is sending a strong message that LGBTQ youth are valid and worthy of celebrating."

Since the group's formation, Keating has witnessed a proliferation of books by or about queer people within the Young Adult genre, the narratives becoming more nuanced and the experiences more representative. The trend has been exciting.

But efforts to blacklist these new titles leave Keating feeling demoralized. "This is adults bullying children," she said.

Hiding behind rainbow flags: These companies' political donations don't match their support of LGBTQ issues

Help from librarians and lawyers

A new public advocacy campaign from the American Library Association called Unite Against Book Bans offers an online toolkit to help people organize their communities, write letters to the editor, contact policymakers and speak up during comment periods at board meetings.

One of the campaign's partners is the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, which along with other legal organizations has disseminated resources on free expression and advice on how to navigate book challenges in court.

“My days are pretty much phone calls and memo writing and a lot of activity based on helping respond to challenges to these books,” said Jeff Trexler, interim director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, which has offices in New York City and Portland.

Last month, a Republican congressional candidate in Virginia Beach, Virginia, filed a restraining order against Barnes & Noble and the local public school system, seeking to prohibit the two from selling or loaning two books, “A Court of Mist and Fury” and "Gender Queer." Trexler is one of "Gender Queer" author Maia Kobabe’s attorneys on the case.

“We’re dealing with these very broad challenges to a book’s availability and punishment of the people who make it available on a bookshelf or in the library or have it for sale in their store,” Trexler said.

Trexler said visual formats have long had a special appeal to queer authors and writers seeking to explore themes of sexual orientation or gender identity. A relatively large percentage of frequently targeted books are graphic novels.

“The thing about comics is you can be anything you want, you can do anything you want,” Trexler said. “Through comics, you can transcend all the laws of physics – all the restrictions that are on you in society. This is a realm of ultimate freedom, of pure expression.”

Banned books: What censorship does to a child

Individual librarians across the country are also helping their communities navigate book restrictions.

Among the most notable examples is the FReadom Fighters, the group based in Texas. Having begun as a social media initiative in response to book challenges in their states, the FReadom Fighters have led regular letter-writing campaigns, participated in rallies and distributed books alongside student activists.

It's a particularly fraught time to be a librarian: They've faced attacks not just for what’s in their collections but also for what they’re promoting in display cases or whom they're letting on-site, said co-founder Foote. The retired librarian pointed to controversies over Pride exhibits and incidents this month in which men associated with the alt-right Proud Boys extremist group disrupted Drag Queen Story Hour sessions. Through that program, which is run by a nonprofit and often hosted at public libraries, drag queens read stories to children.

The attacks have led to a good degree of self-censorship by librarians, Foote said, who are simultaneously facing growing demand from students for the inclusion of these queer perspectives on shelves and in display cases.

Given the demand for and urgency of the teen e-cards, Brooklyn Public Library has decided to continue the program indefinitely.

"I hope other public libraries that have some sort of influence and authority can get together and start to think how to support their communities," said Nick Higgins, the system's head librarian. “We need more libraries to stand up, and more institutions and organizations to join us in pushing back on censorship in this country.”

Contact Alia Wong at (202) 507-2256 or awong@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @aliaemily.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Want to read banned LGBTQ books? Here's how children can find them