How an LGBTQ library book ban galvanized a small Alabama community

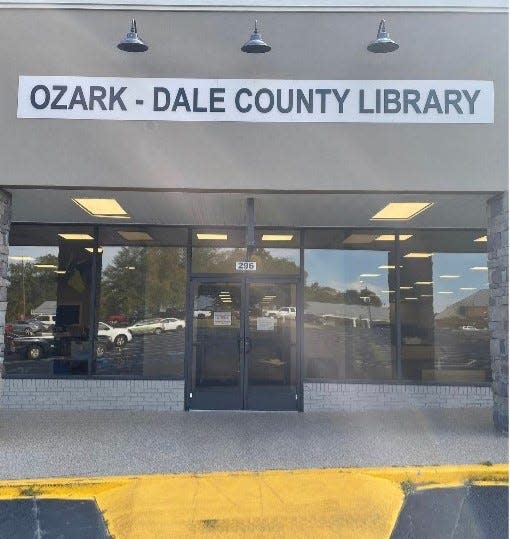

On March 21 at 7:51 a.m., Ozark Mayor Mark Blankenship fired off a text message to Ozark-Dale County Library director Karen Speck and library board member Monica Carroll asking them what he needed to do to get 61 LGBTQ-related books removed from the library.

Carroll joked that she would “bring a match,” and Speck said the mayor needed to fill out paperwork requesting a review at the library.

This conversation launched a months-long conflict centered on the library, its funding and what books it allows minors to check out. Eventually, both sides reached a compromise similar to the one recently implemented in the Autauga-Prattville Public Library: increasing the minimum age of “young adults” in the library from 12 to 14 and requiring parents to sign off on whether or not their child can check out YA books.

Before finding resolution, though, the debate tested the small town on its values and brought many typically quiet residents out of their homes and into the public discourse.

The concerns that started it all

The Montgomery Advertiser reviewed the March 21 text conversation and others that it obtained from Ozark resident Adam Kamerer, who received them via public records request.

After some back and forth over several months about the necessary process to remove books from the public library, Blankenship complained that the books had not been removed by August.

“In Ozark, Alabama, the large majority of people don’t want to see this in our library,” Blankenship said in one message. “100% of my city council will agree. I hate to see the library lose funding over this mess!”

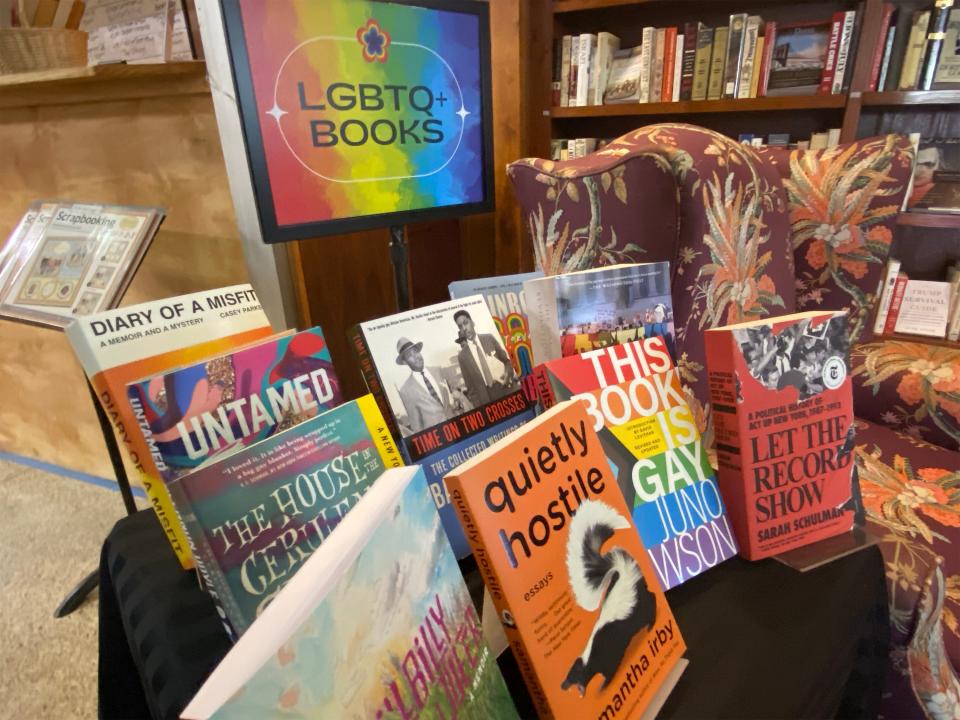

Shortly thereafter, the library board voted to keep the books labeled as “LGBTQ” and “YA” in the young adult section of the library, instead of relocating them to the adult section as Blankenship wanted.

Some of the books he took issue with on account of their “sexualized” content included: a coming-of-age novel about drag titled “The Black Flamingo” by Dean Atta, a theater camp mystery with a nonbinary character titled “Twelfth” by Janet Key and a novel about immigration featuring a gay main character titled “The Grief Keeper” by Alexandra Villasante. The authors of all of these books identify them as “young adult fiction.”

Speck asserted via text that moving the books would be censorship and getting rid of the entire section was not an option. Around the same time, the library board planned a special meeting to discuss the informal request to remove all LGBTQ books from the young adult section, and that’s when the mayor publicly announced his support for the removal.

On Friday, Aug. 25, Blankenship and his wife posted a statement to their joint Facebook account.

“We have been trying to remove this trash from the kids section of our library for several months. We have been told several times it would be removed. It never happens and the library receives three or four more books per month,” the statement read, in part. “If we cut the funding, they will be closed, and our children will not be exposed to this mess. It’s time the majority of the people stand up and address this liberal mess in Alabama.”

Along with the statement, the Blankenships included information about a special board meeting to discuss how the library should respond to “an informal request to remove all LGBTQ books from the Young Adult section.” It would be open to the public.

A community galvanized

Kamerer, the resident who acquired Blankenship’s texts via public records request, grew up going to the Ozark-Dale County Library. An avid reader from a young age, Kamerer remembers walking through the front doors with his mother once a week and traipsing through the stacks until he would land on the next book that called out to him.

“I strongly believe that libraries are one of the most sacred places that we have in America,” he said.

Since returning to his hometown a few years ago, Kamerer has become an involved patron of the library. That is likely the reason why many of his friends and neighbors turned to him for answers when they heard about the mayor’s Facebook post.

“My phone started blowing up,” he said. “Initially, when that post came out, there was a lot of confusion.”

The public didn’t know that Blankenship had been pushing for LGBTQ books to be removed from the library since March, or whether he was actually behind the post on his joint Facebook account with his wife, or how quickly the situation would snowball from there.

“He is the first and only mayor of Ozark to ever threaten to close or defund the Ozark-Dale County Public Library, and that library has been in operation since the 1950s,” Kamerer said. “Apparently, he thought that he would get a lot of support for that, and I think that spectacularly backfired and didn't turn out the way he expected it to when he made that post.”

Kamerer isn’t part of the LGBTQ community himself, but he took the mayor’s statement personally as an ally to the community. The day after the post went live, he created the Ozark-Dale Library Alliance, a group organized to stand in support of the library and its inclusion of LGBTQ books. In less than two months, the group’s membership has rocketed to more than 1,000 people.

The alliance has had a presence at every public meeting about the library, the first of which was on Aug. 30, and Kamerer said those with the alliance have outnumbered the opposing side.

Personal and collective growth

One resident who joined the alliance is Nate Sidebottom. He married his husband in 2021, and he's lived in Alabama for nearly two decades. Most of those years have been spent in Dale County.

Up until the library debacle, Sidebottom said, the LGBTQ community in and around Ozark hasn’t been a problem, a focus or anything, really.

“It’s been pretty quiet,” he said. “Ozark is a very small, good old boy community. As long as you don’t ruffle any feathers, they’re not going to bother you. Nobody goes out of their way to be hateful, so we haven’t felt any kind of prejudice here.”

Rhonda Childers, an alliance member whose son is gay, said she’s never known there to be a “coordinated LGBTQ community” in Ozark.

“Not yet anyway. I’m hoping that something may come out of this because everybody has shown such good support,” Childers said. “I just feel like I need to speak out for and represent the LGBTQ youth and let parents know that it's okay to love and accept your child.”

Coming from a strong Christian background, Childers believes that if this same situation would have happened 14 years ago, she would have fought to remove the LGBTQ books. That was before her son came out.

It happened when he was a teenager, a few weeks after he left the hospital for depression and suicidal ideation. In the car on the way to a family dinner, Childers asked her son point blank, and when he said yes, her husband just said, “You know how we feel about that.”

Once they arrived at the restaurant, Childers’s son was visibly shaking, and that was the moment everything shifted. Her husband reached across the table and told him nothing would ever change how much his parents love him.

“You could just visibly see the weight lifted off his shoulders,” Childers said. “The turning point for us was there. It was right then that we realized the harm that had been done and that we could have lost our child.”

From that point forward, Childers threw her heart into understanding her son and coalescing that acceptance with her Christian faith. One documentary she recommends to parents in the same position is “For the Bible Tells Me So.”

Now, the health and wellbeing of LGBTQ youth is an issue close to her heart. When Childers saw Mayor Blankenship’s stance on the library books, she didn’t see a choice in what she would do next.

The only option was to join the group fighting it, and she was shocked by how many people had the same thought process.

“I'm proud of our little town that they have shown their support, supported the library and supported the LGBTQ community,” Childers said. “Even the ones who made a point to say they don't agree with it, but they don't agree with banning books either.”

To provide support for the Ozark-Dale County Library Alliance, readers may visit the group’s Facebook page.

Where Ozark fits into the bigger picture

When Mayor Blankenship sent that first text to library leadership about removing LGBTQ books, he wasn’t the only local leader thinking about restricting what content kids can access in public libraries.

That same day, a Missouri lawmaker moved to strip funding from public libraries that allow “sexually explicit material” on their shelves. A South Carolina library board hosted a public meeting to discuss what to do with its children’s books that include LGBTQ characters and themes. A Florida school board voted to keep four challenged books in its libraries.

The issue was not unique to Ozark as a community. It’s been everywhere.

The American Library Association’s preliminary data on attempted or proposed censorship in public libraries shows a significant surge in 2023. Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 31, ALA found 695 attempts to censor library materials in the U.S., a number that is up 20% from that same span of time in 2022. ALA stated in its report that 2022 saw the highest number of book challenges since the group began compiling this data over two decades ago.

Of 2022’s most challenged books, the majority were challenged because of their LGBTQ content.

In early September, before Ozark reached resolution, Gov. Kay Ivey even had something to say on the matter. She wrote a letter to the head of the Alabama Public Library Service expressing concern about the environment that libraries are providing for parents and their children.

Ivey specifically called out the Ozark-Dale County Library for its inclusion of two books with “graphic sex scenes” in the YA section.

“As several parents have eloquently put it, their concern is not about removing these books,” she wrote. “The concern is about ensuring that these books are placed in an appropriate location.”

After both Ozark and Prattville implemented their new policies to protect parent supervision without removing any LGBTQ books, Ivey authored another letter to the Alabama Public Library Service, requesting to make local libraries’ funding contingent upon their implementation of certain policy changes. These include having structures in place for community members to request the relocation of

For the time being, it’s unclear whether the agency will implement Ivey’s proposed changes statewide, but either way, LGBTQ books in public libraries will likely remain a prevalent topic of discussion for the foreseeable future.

Hadley Hitson covers children's health, education and welfare for the Montgomery Advertiser. She can be reached at hhitson@gannett.com. To support her work, subscribe to the Advertiser.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: How Dale County's quiet LGBTQ community defended the community library