Will license plate reader use expand to all of Nashville? Council to decide Tuesday

The potential expansion of automatic license plate readers across Davidson County lies in the hands of Nashville's council.

On Tuesday, in the final meeting of the term, Council members will consider legislation that would greenlight full implementation of the cameras across Nashville.

The Metro Nashville Police Department concluded a six-month pilot program of the technology on July 22, which itself narrowly passed Council scrutiny in February 2022.

The cameras capture images of every license plate and vehicle that passes. Legislation for the pilot program limited law enforcement use to comparing plate numbers to those linked in national crime databases to missing persons cases, felony offenses, violent crimes, reckless driving, and stolen vehicles and license plates.

Over the six-month period, cameras read about 71 million license plates, ultimately resulting in 112 arrests.

Proponents of the technology, known as LPRs, say the cameras are a powerful tool to aid Nashville's police force in solving crime, recovering stolen vehicles and locating missing people. At a council committee meeting on Aug. 1, Haynes Park resident and neighborhood association board member Gina Coleman recounted her community's efforts to fundraise for private LPR installation in 2020 after a series of shootouts and arrests in the area.

But numerous community organizations have consistently urged against LPR use, citing instances of mistakes or misuse that put people in danger, risks of disproportionate impact on minority communities, and the potential threat of state or federal officials obtaining LPR data for purposes like immigration enforcement.

More: Where mayoral candidates stand on license plate readers in Nashville

The results of the pilot program, they said, do not assuage their concerns.

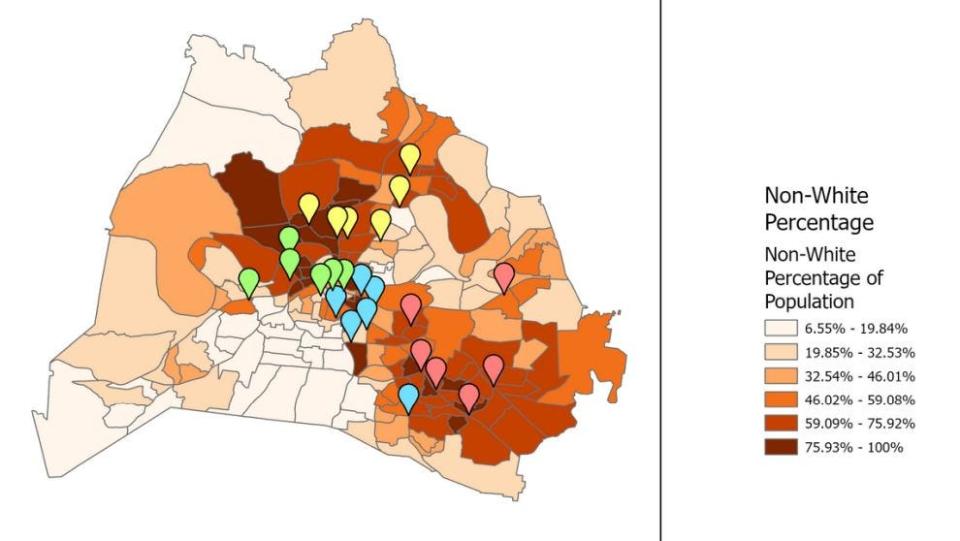

Nashville's police oversight board released a report in June examining the first three months of the city's LPR pilot program, finding the devices were largely concentrated in non-white, low-income areas. Parts of North Nashville, East Nashville and Madison saw more LPR-related stops, searches, arrests and vehicle recoveries than any other part of the city. MNPD representatives said the locations were not chosen using racial or economic data, and the department has received no complaints about the technology during the pilot program.

The oversight board and community organizations say Nashville needs more than a couple weeks to analyze and learn from the pilot program. Questions remain unanswered: How often do misreads occur? Where would cameras be located? How much will the expansion cost? What is the return on investment?

"Please take a second to fully digest the data, to fully understand how discriminatory this pilot program has been, and how important it is for myself, for other community members ... to feel like we're being heard and for our questions to be answered as to the placement of these license plate readers and the future of our city when it comes to surveillance technology," community organizer Cathy Carrillo told members of the council.

License plate reader cost and placement

MNPD Deputy Chief Greg Blair said the six fixed-location pilot program cameras in each of the four city quadrants were placed based on violent crime data from 2021 to 2022. They were arranged in clusters to allow the technology to "get multiple hits" and indicate a direction of travel that would make it easier to take a suspect into custody, he said in a presentation to council committees on Aug. 1.

Mobile LPRs moved throughout the county.

"There's no way we could do a pilot program and cover every inch of this county," he said. "It would be too much money and too much burden on our vendors."

The pilot program served as a type of audition for the technology and its providers. The cost of an expansion is unknown because bids are confidential while Metro is engaged in a procurement process. That process is currently on pause, but should the council approve expansion on Tuesday, procurement could be complete by late September or early October, Blair said.

If the council does not approve the resolution on Tuesday, MNPD must cease using the LPR technology.

Last August, the city council of Concord, California — a bay area city home to about 125,000 people — approved up to roughly $789,000 for the purchase of 65 LPRs and software to match from Atlanta-based LPR company Flock Safety.

Nashville police, district attorney see pilot as success

Before a plate number can be sent to dispatch for action, two officers and an LPR program administrator (a command-level sworn MNPD officer who manages the LPR program) must verify the hit is valid using the National Crime Information Center law enforcement database.

The pilot program saw 1,316 verified hits, according to the oversight board's analysis.

LPRs were connected to the recovery of 14 guns, 87 vehicles and 14 license plates.

Blair shared stories of the technology being used in cases that led to arrests. Police used LPRs to help identify a 16-year-old and recover from his room licenses, ID cards, keys, license plates, ammunition and machines used to make key fobs. Arrests like this allow law enforcement a chance to intervene, he said.

"This is a 16-year-old kid, and if he keeps going down this path, he's going to go down the wrong way."

Nashville Assistant District Attorney Jenny Charles recounted a case in which a license plate reader was used to identify a stolen vehicle used by a man who is now serving time for homicide using a firearm.

"Mass incarceration is an injustice, wrongful convictions are an injustice, and crime is also an injustice, and people having their bodies maimed and shot with firearms," Charles said. "These cases going unsolved is an injustice. We need every tool in our toolbox to solve these crimes, and license plate readers are an important part of that."

Oversight board: Technology has scant recovery rate

The Metro Nashville Community Oversight Board requested more detailed pilot program data from May 7 through May 17, finding the rate of verified hits, recoveries and apprehensions as a result of using the technology to be scant.

About 3.5 million scans in the 10-day period resulted in around 1,400 hits (a hit rate of 0.041%). Of those, about 119 hits were verified (a verified hit rate of 0.0033%). The recovery and apprehension rate for that period was about 0.00025%, according to MNCO Digital Evidence and Data Analyst Dylan DePriest.

He said a cost effectiveness audit is necessary before a full LPR rollout. Blair said the limited number of overall arrests during the pilot period is evidence of "precision policing."

Of the 35 people arrested from May 7 through 17, nearly 49% of them were Black, and around 8.6% were unhoused, DePriest said. Sixty percent had force used against them, and of those, nearly 62% were Black.

He said more time is needed to do further research on topics spanning types of warrants, charges, the resident status of those arrested, rates of false hits and the impact of LPRs on houseless individuals, "since we saw a surprisingly high rate in the arrest data we had access to."

MNPD reported that of the 112 people arrested through the duration of the pilot program (81 adults and 31 juveniles), 103 had a local criminal history, having been arrested a collective 829 times under charges including violent felonies, robbery, auto theft, burglary, misdemeanor assault, and drug and gun infractions.

Because the most law enforcement outcomes occurred in non-white and low-income areas, DePriest said MNPD should release the locations of the 117 prospective cameras to the council and public, "to ensure the requirement of equitable distribution is met."

Community groups say risks are 'just too big'

Judith Clerjeune, campaigns and advocacy director for the Tennessee Immigrant & Refugee Rights Coalition, said the risks are "just too big."

"It's hopefully common sense that we would actually do the due diligence necessary before committing all of us to something that might have drastic and unforeseen consequences to the community," she said, noting that there is no way to secure LPR data from the state.

The data is wiped after 10 days unless it is evidence in a criminal investigation.

The council has passed additional legislation barring LPR data use for anti-abortion law enforcement and restricting data use for immigration enforcement, but the strength of those barricades could have limited efficacy if faced with subpoenas. Per state and federal law, Metro could still use LPR data to verify or report a person's immigration status.

Emily Herbert, a deputy public defender in Nashville, said she believes LPRs will have a disproportionate impact on her office's clients.

"We're choosing to cede our privacy interests in the interest of public safety, (but) public safety doesn't just encompass solving crimes," she said. "It encompasses preventing crimes. We could be investing in a better educational system, we could be investing in community mental health care."

MNCO Executive Director Jill Fitcheard said the oversight board hasn't received a formal complaint about LPR use, but clarified that citizens stopped as a result of an LPR hit would not be aware unless an officer informed them. And even then, the waters are muddy: The use of an LPR does not, in itself, constitute misconduct.

"The feedback that we have received is more informed, and it's more sincere," she said. "People are concerned about the overall use of LPRs and their placement in low-income and non-white areas of the city. They are concerned about Nashville becoming a surveillance city, specifically one where the racial and social economic disparities of our criminal justice system are exasperated by technology. They are concerned that LPRs are opening the door to facial recognition technology."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Will Nashville expand license plate reader use by police?