'Life saver' skin patch to detect, instantly reverse drug overdose in development

INDIANAPOLIS — What does an opioid overdose look like?

Sometimes it's a sleeping cancer patient, whose recent dosage change led to unforeseen and unmonitored complications. Other times, it's someone with a substance abuse disorder, whose isolated recreational use prevented quick discovery.

Regardless of circumstance, an overdosing person will die if not found and treated in time.

Since a drug overdose can take away one's muscle movement, speech and coherency, it's usually up to people nearby to recognize the signs — shallow breathing, pinprick pupils, discoloring lips — and call emergency responders or, if they have it, administer naloxone, a medicine that can rapidly reverse an opioid overdose.

Quick detection and treatment can save an overdosing person's life, but it puts the responsibility on a nearby individual to know what to do and have the resources on hand to do it.

Rising number of deaths: More than 107,000 Americans died from overdoses last year. This drug is behind most deaths.

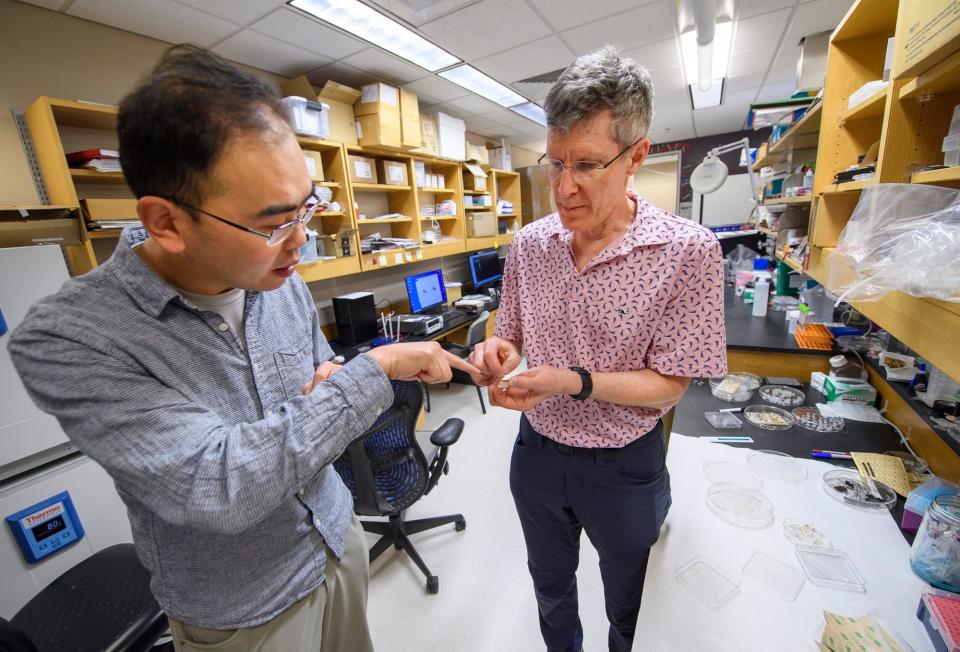

That's why two researchers from Indiana University, Feng Guo and Ken Mackie, are developing a wearable device that can both detect and treat an opioid overdose as it happens.

"(The device) could be really convenient because they don't really need a kind of specialist or bystander to have the (naloxone). It could be a kind of automated system to save that person's life," Guo said. "That's why Ken and I think this could be a life saver for the opioid overdosing patient."

Still in its early stages of development, the project recently received $3.8 million in federal funding to continue research on the Bloomington, Indiana, campus.

Health monitor patch is 'automated system to save a person's life'

Guo and Mackie are creating a microneedle skin patch. Projected to be slightly thicker than a nicotine patch, it has two purposes: detect and treat an overdose.

In order to detect a potentially fatal overdose, the patch will continually monitor a person's respiratory rate, blood oxygen levels, blood pressure and pulse rate. The device's artificial intelligence component should recognize and determine what is considered abnormal for the user's individual health, and the patch also includes a failsafe triggered once it senses an extreme change in oxygen saturation and breathing rate.

"You kind of always design a device like this to have multiple levels of backup because different people are different physiologically," Mackie said.

Once the sensor is triggered, a tiny needle containing naloxone within the patch will be administered through the skin. The user's smartphone, connected to the patch via an app, also will immediately contact emergency services.

The device was conceptualized by Guo and Mackie, Indiana University faculty members and long-time collaborators. Guo already had developed an idea of administering drugs through the skin by using sound waves when Mackie, whose background is in anesthesiology, wondered how the technology could be used to treat an opioid overdose.

'The world doesn’t care': Homeless deaths spiked during pandemic, not from COVID. From drugs.

Opioid epidemic persists

The most recent data indicates the ongoing national opioid epidemic is far from slowing down. Between April 2020 and April 2021, the National Center for Health Statistics estimated there were about 75,673 overdose deaths from opioids in the United States, a nearly 35% increase from last year during the same period.

An opioid overdose can happen even when the person takes an opioid as directed. For example, the prescriber may have miscalculated the dose or an error was made by the dispensing pharmacist.

Patients who take opioids therapeutically could be at risk whenever their dosage changes or they move from one narcotic to another, Mackie said.

"That person, in particular, has increased risk for respiratory depression overdose. Unfortunately, that often occurs, say when they're sleeping, so no one's around them. This would be a very good device for that kind of situation," Mackie said.

The device's target audience is those who use opioids therapeutically in a health care setting with limited resources.

"You have limited health care resources, where you may not necessarily be able to monitor patients who are receiving opioids as closely as we would normally in a healthcare setting," Mackie said, such as a mass casualty event or military use.

However, Mackie noted the device potentially could be used by those who have substance abuse disorders.

"That gets into a very controversial field, because on one hand, you want to do that. But on the other hand, would having a sort of safety net like this encourage irresponsible use of opioids? That's always a concern," Mackie said, noting the same concern was voiced when naloxone became available in a nasal spray.

As a physician, Mackie said he wants to provide people with as many options for improving their health as possible and this device is one way to do so.

"If it saves five people but encourages five people to use opioids, I focus on the value of saving five lives rather than encouraging five people to use opioids," Mackie said.

Guo and Mackie have been working on the device for two years with promising results, leading to a grant through the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

'Drugs have gotten more dangerous': Teen overdose deaths are spiking despite drug usage falling, study finds

The patch's journey from mice to men

So far, Indiana University researchers have tested the technology on lab rats with primitive results indicating accuracy of more than 93%. Researchers intend to increase the accuracy to over 98% while scaling up the technology for human use.

Guo and Mackie also have been collaborating with researchers from other universities.

Greg Terman and Jake Sunshine, anesthesiologists and pain physicians from the University of Washington, have been collecting physiological data from people taking opioids under a physician's care as well as those with an opioid use disorder. Larry Cheng, an engineer at Penn State University, is helping to fabricate the sensors for monitoring physiological parameters.

According to Guo, who has experience in the biomedical device field, a project like this usually takes seven to 10 years from the first idea to a product on the shelf.

These researchers are focused on the next step: building a prototype.

"Our goal for the end of this three-year project is to have basically a prototype device that will be able to be used for humans. I would say we're maybe a third of the way along that process," Mackie said.

Follow Rachel Smith on Twitter: @RachelSmithNews.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Researchers tackle US drug overdose crisis at Indiana University