A lifetime of high-points: hiker Robert Packard looks back on his career

In an unassuming apartment nestled amongst Flagstaff's tree-lined neighborhoods lives a decorated record-holder and pioneer in his sport. Now 86, Robert "Bob" Packard has spent the better part of the last six decades making his way up mountainsides and up the rankings as one of the most accomplished people in his sport.

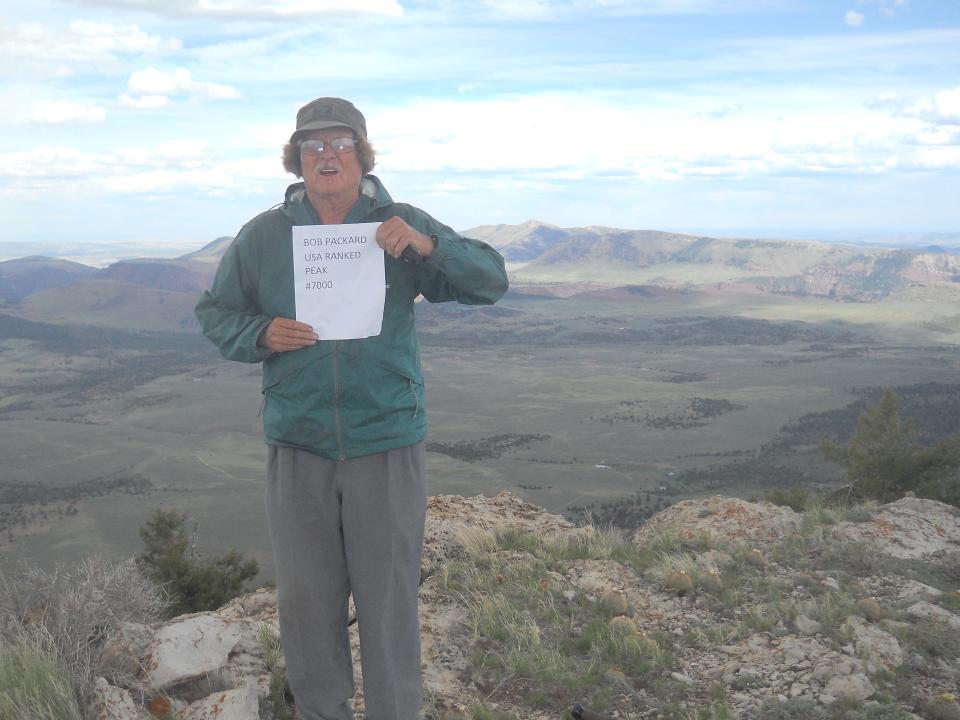

Packard now holds the distinction as one of just three people to have hiked the entire length of the Grand Canyon on both sides of the Colorado River and is the current leader in all-time peaks, summiting more than 7,000 throughout his life in addition to a slew of other accomplishments in the sport.

Now with some help from a pacemaker, Packard has slowed down, but isn't quite done yet.

Early Beginnings

For much of his childhood, spent outside on his family's farm in rural Maine, the outdoors were a place for work, not exploration or hiking.

"Growing up on the farm was where I got lessons in hard work," he said.

His parents both worked, but the farm served as a way for his family to save money on food, Packard said, and everyone pitched in. The oldest of five children, Packard spent his days after school milking cows, slopping pigs and digging potatoes.

Packard eventually made his way to Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, where he went on his first few hikes, planting the seed for a passion that would ultimately grow when he moved out west.

From there, Packard earned his Ph.D. in mathematics from Dartmouth College and was soon on the hunt for a teaching position and somewhere to settle down with his young family — ideally somewhere that would allow for further exploring.

He would ultimately join Northern Arizona University as a mathematics instructor and move his family more than 2,000 miles west to Flagstaff. Packard found familiarity in the pine trees that populate the mountain town, harkening back to Maine's moniker as "The Pine Tree State," but he also saw endless possibilities in the areas that were completely new to him.

"It's close to desert country and mountains and canyon country," Packard said. "I guess that's one of the things that attracted me to Flagstaff, the fact that it wouldn't be a big transition as far as the local everyday climate, but it would be close to really exotic areas."

Luckily for Packard, NAU's mathematics department was already home to another pioneering hiker, Harvey Butchart, who by that time had already established a reputation as one of the foremost explorers of the Grand Canyon. Packard was quickly taken under his wing.

"One of the reasons I came to Flagstaff was to meet him and to get near canyon country, and I figured, well, I’ll do a sample of this and that and I ended up, I think I’m probably one of the 10 most prominent hikers of the Grand Canyon,” Packard said. “But I had not planned it that way, just like I didn’t have it planned early on in my that I would have so many summits around the world.”

His dedication to the trails in those years even prompted his then-wife to refer to the Grand Canyon as Packard's "mistress."

Packard finished hiking the length of the south side of the Grand Canyon in 1998 when he was 61 and completed the north side just two years later, becoming one of just three people who have accomplished the task to this day. Besides Packard, Robert Benson and Andrew Holycross have completed the hike, with Holycross completing it in 2013.

"I did my first 30 hikes in the Grand Canyon with [Butchart]," Packard said. "I would have to say that whatever I did in the Grand Canyon was either following in his footsteps or standing on his shoulders."

Changing goals

Packard didn't start his hiking career with lofty goals. Instead, one trip led to another and he eventually realized he'd done a lot more than he thought, he said. In some cases, he was actually quite close to achieving some major accomplishments.

"I had no intention of walking the full length of the Grand Canyon when I started off, but it got to a point I'd go up there weekend after weekend after weekend, and gradually I noticed that I don't really have that much further to go," he said.

Over time, his goals have changed as he stumbled onto new aspirations. His focus shifted from conquering all of the 14,000-foot peaks in the U.S. to the 13,000-foot peaks and so on.

"One thing led to another and I got into state high-pointing," he said.

It was his son, Erik, who as a teenager first suggested his father try to reach all of the high points in Arizona's 15 counties.

Packard eventually became the first person to reach all of the county high points across the western U.S. and he also reached the high points of all 50 states in 1995, including an 18-day trek up Alaska's Mt. McKinley.

Erik is now an accomplished climber and mathematician in Colorado and he can still remember joining his father on hikes growing up, including making their way up Mt. Humphrey's peak at seven as his dad carried his younger brother.

Their adventures together gradually evolved from completing his first 14,000 ft. summit at 12 years old to eventually summiting Mt. McKinley together in 1990.

Evolving alongside his sport

Throughout his lifetime, advances in mapping, radar and other technology have gradually altered the sport that used to require an advanced knowledge of map-reading and navigational skills.

"You're kind of doing it just by the bootstrings with very little information at the beginning," he said. "And remember that when I was doing the majority of my hobby, you didn't have GPS."

When Packard first started doing state high points, for example, he simply grabbed a Rand McNally highway map that noted each state's high point and began making his way through the list. It was only years later that advancements in radar technology started to record new elevation measurements, sometimes changing the state's high-point altogether.

As a result, he's had to return to a handful of states to reach the new high point, some that were just a short trip away with a very minor elevation change, but he doesn't feel the need to go back to all of them. Instead, he's content with having completed his original list.

"There's kind of a general agreement amongst the people in this hobby if you have finished a list under the circumstances that at the time it was thought to be the list, then you get credit," he said.

Packard has also started to lessen his activity with age. He can't move as quickly as he used to and elevation changes impact him more than they ever have before, he said.

With the assistance of a pacemaker, Packard's career has slowed but has not stopped, evidenced by his recent 3,000th Arizona summit.

And while Erik has noticed his father has slowed down in recent years, when they're out on the trail together he's often surprised by just how quick his father still is on the mountain.

Just like he looked up to Butchart, Packard has developed a reputation as one of the fathers of the sport.

Erik remembers a particular instance when a group of young hikers recognized his father and crowded around him like he was a celebrity.

"There were like 10 people around him like he was Lebron James," Erik said with a laugh.

But Packard sees it more as a natural progression of the sport. He had his heroes to look up to and while he might serve in that role for someone else now, eventually, the next generation of prolific hikers and climbers will emerge.

"It’s very important to point out that it’s a generational thing, namely, that there are always people ahead of you that you admire and aspire to be like," he said. "And now I’m in a position in my life where there are other people behind me aspiring to be what I’m like."

Do you have an inspiring neighbor, colleague or friend you think should be featured in Faces of Arizona? Let us know by filling out this form.

Contact northern Arizona reporter Lacey Latch at llatch@gannett.com or on social media @laceylatch. Coverage of northern Arizona on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is funded by the nonprofit Report for America and a grant from the Vitalyst Health Foundation in association with The Arizona Republic.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: A lifetime of high-points: hiker Robert Packard looks back on his career