When Lincoln Entered Richmond as a Leader, Not a Conqueror

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

April 4, 1865

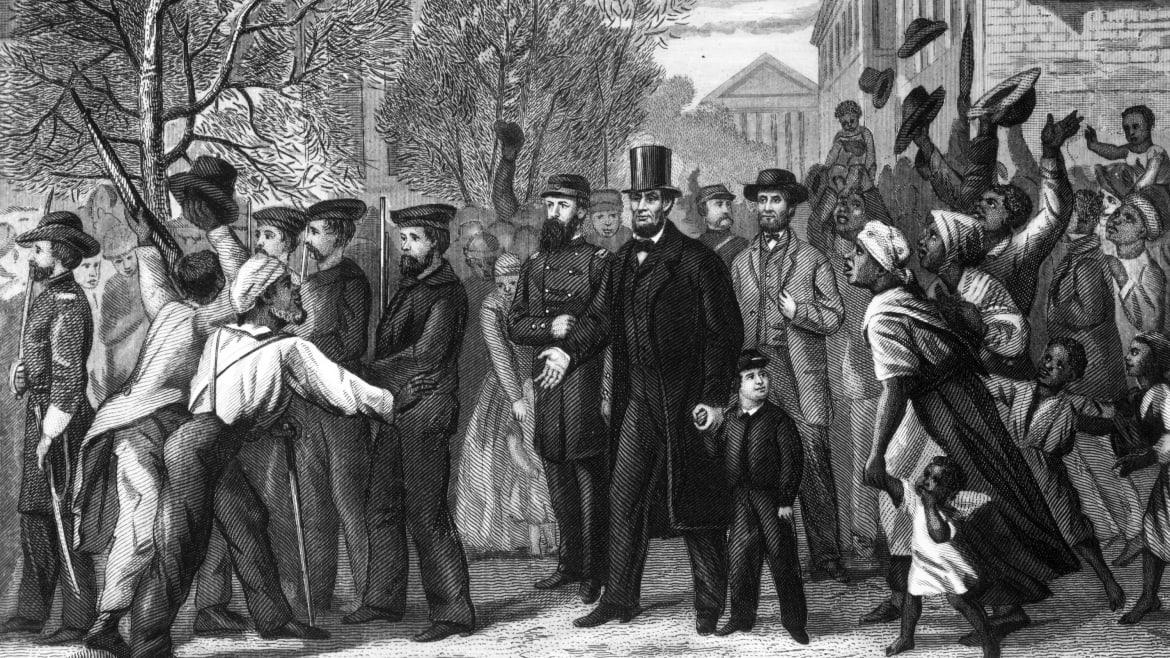

Abraham Lincoln walked into the burning Confederate capital, uphill from the river, passing abandoned slave markets on his right, holding his son Tad’s hand on the boy’s 12th birthday.

After four years of civil war, the president of the United States was in Richmond. Now he knew all the suffering had not been in vain: liberty and union would defeat slavery and secession.

He did not stride into the city like a conquering hero, flanked by a vast army. Instead, he arrived on a longboat with a small crew including an admiral, a bodyguard, and a dozen sailors, who acted as oarsmen. There was no military escort waiting to greet them as they scraped ashore. They were strangers in a strange land, wandering past burned-out buildings that jutted up like tombstones as smoke billowed against a blue sky.

How Lincoln Triumphed in an Era Even More Toxic Than Ours

A low murmur rose among the ruins at the sight of the 6-foot-4-inch man in black, slightly stooped, topped by his signature stovepipe hat. It was the sound of rumor turning to revelation. A crowd of liberated slaves gathered around Lincoln. They grabbed at his clothes and fell at his feet. “Don’t kneel to me,” Lincoln gently rebuked them. “That is not right. You must kneel to God only and thank Him for the liberty you will afterward enjoy.”

Thomas Morris Chester, a pioneering Black war correspondent for The Philadelphia Press, was among the first journalists to see Lincoln enter the rebel capital and he scribbled down the celebration. “Old men thanked God in a very boisterous manner, and old women shouted upon the pavement as high as they had ever done at a religious revival,” he wrote. “There were many whites in the crowd, but they were lost in the great concourse of American citizens of African descent. Those who lived in the finest houses either stood motionless upon their steps or merely peeped through the window blinds.”

It seemed that the meek would finally inherit the earth, or at least Richmond.

Death hovered over his shoulder. Surrounded by rowdy crowds, Lincoln’s bodyguard thought he spied a sharpshooter in a second-floor window point a rifle at the president and trace his path without firing a shot.

Lincoln and Tad were caught in the eye of a human hurricane, winding up the road toward the marble capitol building on the top of the hill, passing the place where Virginia ratified the U.S. Constitution fewer than eighty years before.

It was an uphill climb and beads of sweat collected on their dust-covered faces. As Lincoln stopped to wipe his brow, an older Black man approached the president and took off his hat, placing it over his heart, saying, “May the Good Lord Bless You, President Lincoln.” The president responded by removing his own hat and bowed in return.

“It was a bow which upset the forms, laws, customs and ceremonies of centuries,” observed Charles Coffin of the Boston Journal. “It was a death shock to chivalry, and a mortal wound to caste.”

As they passed the notorious Libby Prison, where more than 1,000 Union officers had been held in horrific conditions, Lincoln pointed out the brick and iron structure to his son. The crowd shouted, “Tear it down!” but the president raised his hand and quieted them, saying, “No, leave it as a monument.” Healing could not occur by simply erasing history. It would require learning the right lessons, so we were not condemned to repeat it.

As they turned a corner in the city center, soldiers from the New York Fiftieth regiment were shocked to bump into their commander in chief, walking with his “long, careless stride,” one soldier recalled, “looking about with an interested air” as he casually asked them for directions. They marched him up to the steps of the gray stucco executive mansion, abandoned by Confederate president Jefferson Davis and his family the day before, where Union general Godfrey Weitzel, a 29-year-old German immigrant, had set up headquarters.

Entering the tall yellow hallway, flanked by plaster Greek statues representing comedy and tragedy, Lincoln was led to the small ceremonial office on the first floor and sank down into the leather chair behind Jefferson Davis’ desk. As he leaned back, letting his long legs stretch, he looked out the same window that Davis had gazed through so many times before. His face seemed “care-plowed, tempest-tossed,” but close observers always noticed his “kind, shining” eyes. Lincoln ran a hand through his unruly black hair, and asked for a glass of water.

It was a moment of supreme triumph but there was no hint of triumphalism. General Lee’s army had not yet surrendered—that would come five days later at Appomattox Court House. But the Civil War had been won.

The past four years had been defined by political crisis and personal despair: the death of his beloved 11-year-old son Willie, the death of friends in battle, and the near death of the Union under his watch. His own family had been divided, with Mary’s brothers fighting for the Confederacy, while his marriage strained to the breaking point. Seven months earlier, Lincoln believed that he would lose reelection.

Now Lincoln was looking forward: vindicated by the people’s vote and determined to stop the cycle of violence, changing his focus from winning the war to winning the peace.

Surrounded by the ghosts of the Confederacy, Lincoln toured the mansion, its tall drawing rooms with crimson wallpaper and cramped living quarters upstairs. He saw military maps that mirrored his own, pinned to the walls of the rebel cabinet room where the stars and stripes now stood.

Lincoln met with his generals around a long dining room table, eager to be briefed on what they had found amid the surviving files of the slave state, while officers toasted with Jefferson Davis’ whiskey and Tad dashed around the mansion.

Reflecting his belief that “public opinion is everything,” the president wanted to get the feeling of the people in the South and asked to meet with a few prominent Richmond residents. Among them was John A. Campbell, the former U.S. Supreme Court Justice turned Confederate assistant Secretary of War. They had met two months before at a secret peace conference at Hampton Roads, Virginia, where Lincoln had refused anything short of unconditional surrender. Now Campbell appealed to Lincoln’s instinct for mercy and moderation, with the manipulative wit to quote the president’s favorite writer, Shakespeare: “when lenity and cruelty play for a kingdom, the gentler gamester is the soonest winner.”

In this twilight between war and peace, the outcome was certain, but the terms were not yet determined. Lincoln repeated his three “indispensable conditions” for peace: no ceasefire before surrender, the restoration of the Union, and the end of slavery for all time. Everything else was negotiable. Lincoln wanted a hard war to be followed by a soft peace; but there would be no compromise on these core principles.

As he walked out of the Confederate White House, Lincoln stopped on the front steps, flanked by Black soldiers in blue uniforms, and spoke to the crowd of freedmen and women. “Although you have been deprived of your God-given rights by your so-called masters, you are now as free as I am… for God created all men free, giving to each the same rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Amid riotous cheers, Lincoln left in a carriage led by four horses, waving to the crowd with Tad by his side, rolling toward the capitol building designed by Thomas Jefferson. Its courtyard was a frenzy of jubilation under the watchful eye of Union soldiers, as worthless Confederate bank notes fluttered in the breeze. Lincoln picked up a torn $5 bill and placed it in his wallet as a keepsake.

Down by the docks at sunset, as Lincoln prepared to board a barge that would take him to his ship for the night, General Weitzel asked him for guidance. How should he treat the traitorous rebels and scared citizens now under his command?

Lincoln characteristically offered advice rather than an order: “We must extinguish our resentments if we expect harmony and union. If I were in your place, I’d let ’em up easy, let ’em up easy.”

Excerpted from ‘Lincoln and The Fight for Peace’ by John Avlon. Copyright © 2022 by John Avlon. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.